The saga of the Baby, the 1972 2002tii that I helped the original owner’s widow sell on Bring a Trailer, is finally complete. The buyer was a little slow on payment, but it got done, and once the money was in the seller’s account, shipping was arranged far quicker than I expected.

The irony was that for all the machinations I typically need to go to through to arrange with the shipper to have the driver meet me not at my house (the street’s too narrow and the trees and power lines are too low) but instead on the wider street on the other side of the park, the truck driver balked and said that even that street was too small for his full-size multi-level hauler. He could’ve backed his rig right into my driveway. Whether the car was being transported this way to a shipping terminal for loading onto something bigger for the long haul out to Beverly Hills, or this was the sole method of conveyance, I don’t know, but it’s gone, off to live the life of Reilly in sunny California.

As Stephen Stills said, “Bye bye baby. Write if you think of it maybe.” And, as Neil Young said, “Long may you run.”

The Baby was at my house for three-and-a-half months. With it gone, my driveway suddenly seemed huge. It certainly made it easier to pull cars in and out of the garage, which was great, because I wanted to address some long-standing carburetion issues on Hampton, my ’73 2002, that required iterative tweak-and-drive cycles.

As you’ve probably read, Hampton is a remarkably original 49,000-mile car that I bought from its original owner three years ago. Before that, it sat in a barn in Bridgehampton for a decade. The first-level sort-out wasn’t too bad, mostly standard clutch hydraulics, cooling system, and center-support-bearing stuff. But the car has always started hard and run lean, and whenever I’ve thought that I’ve gotten to the bottom of it, the problem has reared its head again.

Of course, the fact that I thought I was going to sell the car, was afraid to add mileage to it, and thus kept it in storage, only occasionally allowing it to peek its head out and see daylight, didn’t help matters.

It’s very common for carbureted cars with original mechanical fuel pumps to have problems starting after sitting, because the gas evaporates from the float bowl and the fuel pump has to suck it from the tank to refill it, and any leaks or porosity in the fuel line can make the pump suck air instead of gas. Combine that with an old pump whose diaphragm and pump lever are worn, and it often won’t suck anything at all.

Retrofitting an electric fuel pump nicely solves this problem by pushing rather than sucking fuel, but on an original car like Hampton, I didn’t want to do that. In this piece, I described how, in Hampton, the presence of a large non-original metal fuel filter before the fuel pump created an air cavity that the pump could not overcome, and how the problem appeared to go away when I either removed the filter, put it after the pump, or replaced it with a smaller filter. There’s no question that that helped it pump fuel, but even with a full float bowl, the car was still maddeningly difficult to start after sitting. I suspected that the idle cutoff solenoid was malfunctioning, and when I deleted it, it appeared to solve the problem, but it was a mirage. Adjusting the choke so that it closed tighter has helped enormously, although at cold idle, it’s currently eye-wateringly rich.

Replacing the idle solenoid (left) with a simple jet holder wasn’t the magic bullet I initially thought.

Two years ago, I took a swipe at the lean-running and even-throttle-hesitation issue. I have an old Car-Check portable exhaust analyzer that I bought in a pawn shop when I lived in Austin in the early ’80s. In this piece, I described using it to verify that the car was indeed running way lean, and increasing the size of the primary idle jet from 60 to 65 to 70, at which point it was still lean, but the even-throttle buffeting became much less irksome. Because 70 is a really big idle jet, I wondered if in fact it was masking a vacuum leak, the most likely suspect being the car’s exhaust-gas-recirculation (EGR) plumbing.

I think you’d be hard-pressed to find a 2002 that still has an operational EGR system. On Hampton, the EGR valve and the metal tubing that connects it to the intake and exhaust manifolds were all still there, and I was hesitant to remove the system because I regarded it as providing provenance to the car’s 49,000-mile existence. But the system wasn’t operational, because when the Solex carb was replaced by a Weber sometime in the past, the vacuum dashpot that actuates the EGR was left disconnected. So at best the EGR valve wasn’t recirculating anything, and at worst, it or the plumbing on the intake side was a yawning vacuum leak.

This EGR valve wasn’t doing anyone any good.

So I decided to remove it. The goal was to not destroy the components—not that any future owner of the car would ever reinstall it. That would be like reinserting a tumor. But I thought that I’d add it to the box with the other badges of originality such as the spacers that were on the tops of the front struts for federal headlight height regulations and the “wet strut” cartridges that caused oil to pour all over the garage floor when removed.

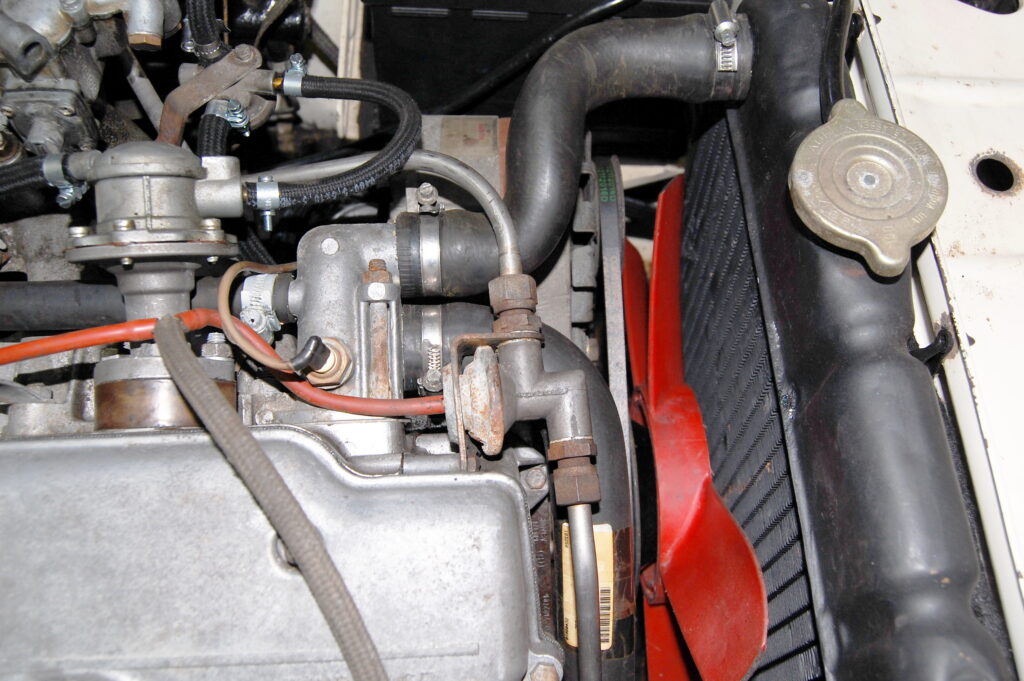

The EGR pipe on the exhaust side snakes down between the manifold and the head, and connects to a little canister on the right side of the block before branching over and connecting to the back of the manifold. So unless you want to unbolt the manifold from the head—and I manifestly did not want to do that—the system has to be taken apart.

The exhaust side of the EGR plumbing.

Not surprisingly, as soon as I put a wrench on the exhaust tubing, the EGR valve cracked in two.

Yup. Done.

After that, I was a bit less reverential about getting the pieces off the engine intact. Let’s just say that at one point a Sawzall was involved.

Out, out!

I’d bought the pieces needed to block off the intake and exhaust ports two years ago. The intake block-off plate is available through bmw2002faq.com here. So on the intake side, this…

…became this:

Getting the port off the back of the exhaust manifold was more challenging. The pipe and its fitting came off the port, taking many of the threads with them. The holy trinity of heat, wax, and leverage convinced the port to let go.

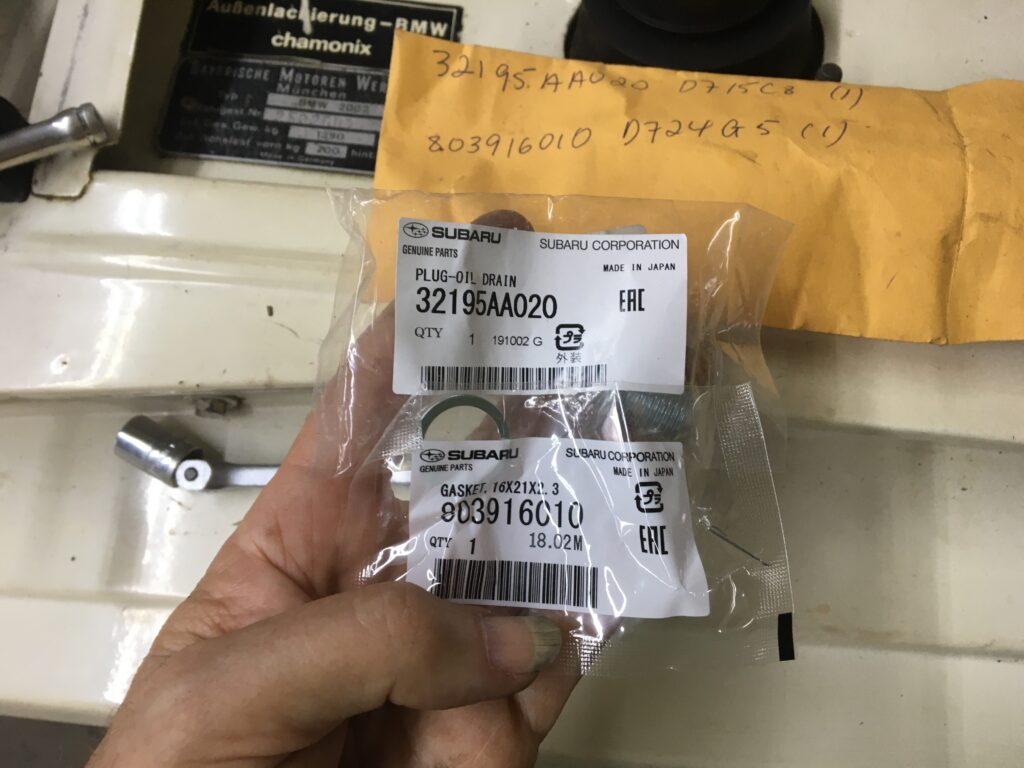

The threads for the exhaust manifold port are M16x1.5. As it happens, that’s the thread pitch for the oil-pan drain plug on a late-model Subaru. I used the plug and the crush washer pictured below. The plug wouldn’t quite thread all the way in, requiring a second crush washer, but other than that it was seamless.

With the EGR gone and the ports plugged up, I hooked up the exhaust-gas analyzer. These days, if you have mixture tuning to do, you buy an ultra-wideband oxygen sensor and an air-fuel gauge, drill a hole in the headpipe, weld in a bung for the sensor, and mount the gauge in the car. But if you have a bunch of cars, being able to move the portable exhaust-gas analyzer between them is very handy.

I hung the probe off the rear bumper, stuffed the hose into the tailpipe, threaded the cable through the right rear vent window, powered the unit off the cigarette-lighter port, let it warm up, zeroed it, and then drove the car. To my surprise, removing the EGR made absolutely no difference: The gauge’s needle still swung lean at even throttle, the buffeting could still be felt, and there was still an obvious numbness on light acceleration.

This 40-year-old portable exhaust-gas analyzer is very handy to own…

… even though I hated the information it was providing.

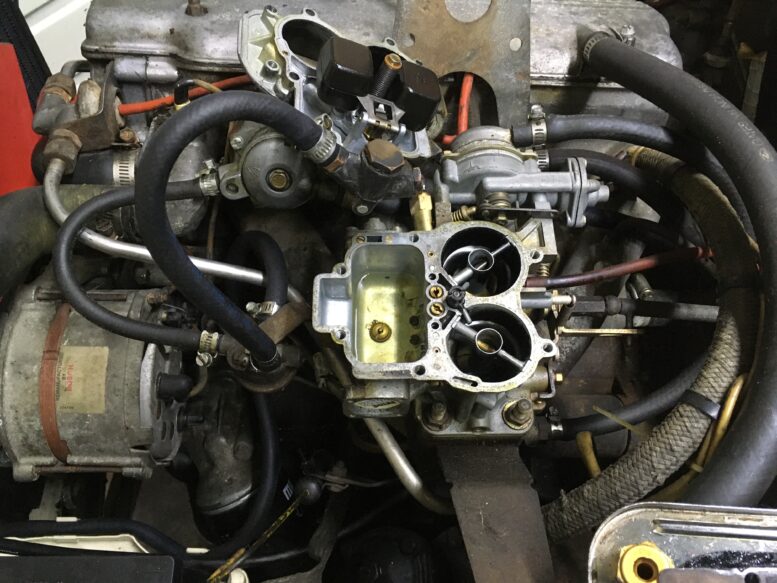

Okay, I know what you’re thinking. When I pulled the car out of its decade-long storage, yes, I pulled the top off the Weber and inspected the float bowl. It wasn’t gooey, varnished, gummed-up horror; there was just a little sediment. So no, I didn’t pull off the carb, take it apart, and let it marinate in a gallon of Berryman ChemDip with its nifty self-contained basket (I’m stunned that you can still buy this product without supplying an OSHA training certificate and a photo of yourself in a Level A hazmat suit). All I did at the time was pull out the jets and blow the passages out with compressed air. So yes, it was possible that the carb was plugged up somewhere internally, and that a higher level of intervention was necessary.

Still, it was also possible that the problem could be handled via simple re-jetting. One is nothing without baseless optimism.

On bmw2002faq.com, you can find a whole variety of Weber jetting prescriptions, the most popular of which was written years ago by BMW technician Creighton Demarest, whose handle on the FAQ is “c.d.iesel.” The “c.d. prescription” is:

| primary | secondary | |

| idle jet | 60 | 55 |

| main jet | 140 | 170 |

| air-correction jet | 145 | 175 |

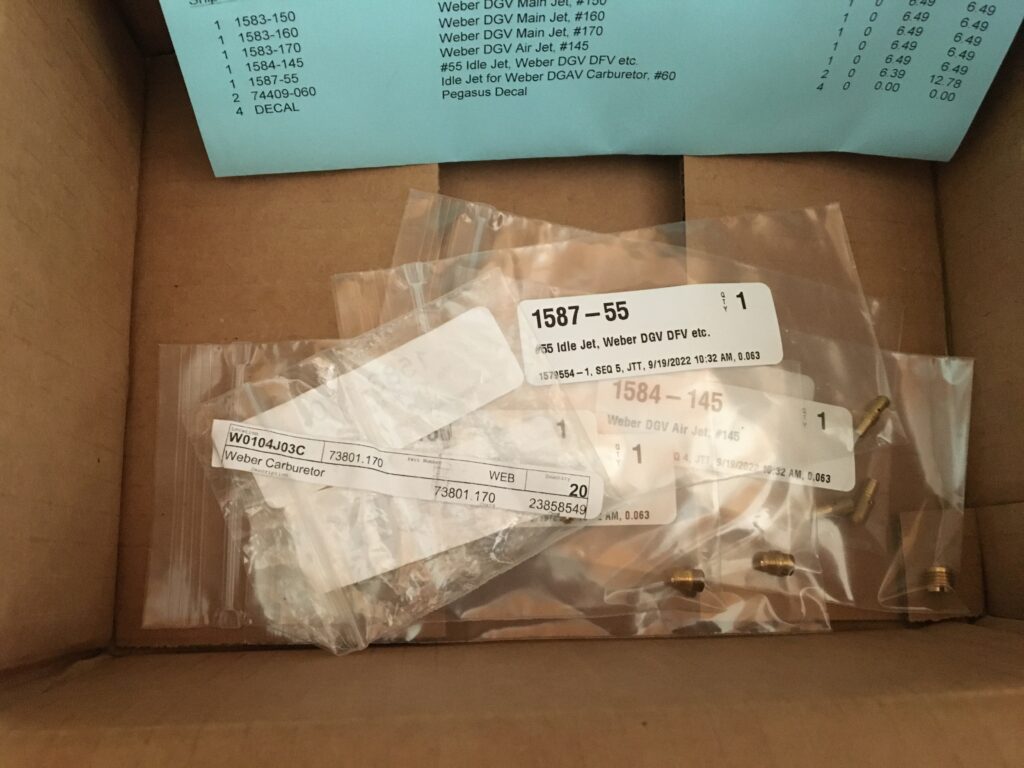

I ordered the required jets from Pegasus Auto Racing Supplies, as well as several additional fatter main jets. The individual jets are about $6.50 each, but it adds up, so along with shipping, and factoring in one jet that Pegasus didn’t have that I needed to order separately, it came to about $85. Still, if it fixed my lean-running problems, it was money well spent.

The box-o’-jets.

When the jets arrived, I pulled the top off the carb, removed all of the old jets, installed the selection to fill c.d.’s prescription, plugged up the secondary enrichment hole, reassembled everything, and drove the car.

Not only wasn’t it better, it was appreciably worse—horribly lean with pronounced even-throttle hesitation. Of course, I had downsized the 70 idle jet back to 60.

I put the 70 idle jet back in, and it felt like it was back at the baseline.

At this point I was glad that I’d ordered several fatter main jets. I went right for the 160 main.

Bingo! The needle no longer swung lean, the even-throttle hesitation lifted, and the flat spot on light acceleration was gone. However, during warm idle and low-rpm running, the car ran very rich. I tested it quite a bit on a variety of around-town and highway driving, and found that I could dial the idle jet back from 70 to 60, adjust the idle mixture, and get an acceptable range of values.

I don’t know that the “c.d. prescription” really did much for me. I think that the big factor was simply the bigger main jet. It’s still eye-wateringly rich at startup from the tight closing of the choke, but I can tweak that until it goes over the edge and the hard starting returns, then dial it back.

Here’s hoping that, this time, I finally have gotten to the bottom of the hard-starting and lean-running problems. With the now correctly performing Weber added to the Bilsteins I installed last fall and the Konig driver’s seat I installed last week, Hampton is now, for the first time in the three years I’ve owned it, approaching actually being fun to drive.

However, in a Hack Mechanic world where I also own Louie the ’72 tii and Bertha the snotty heavily patinaed former-track-rat ’75 with the 10:1 pistons, hot cam, and dual 40DCOEs, both of which have sport springs and thicker sway bars, Hampton has stiff competition (literally) for my enthusiast-driving attentions. I still don’t see it as the 2002 that I’ll jump into and do stress-busting corner-carving; it still feels more like a Sunday yard sale “Oooh, I knew a guy who had one of those back in college” car. Not that there’s anything wrong with that.

Of course, neither of those two other 2002s is here right now—they’re out in the warehouse in Monson. There’s a BMW day coming up at the nearby Larz Anderson auto museum, and an autumn drive with the Nor’East 02ers in late October. I think the time is nigh for Hampton to get its close-up, spend some quality time with his BMW brothers and sisters, and get some New England autumn mileage on him.—Rob Siegel

Rob’s new book, The Best of The Hack Mechanic, is available here on Amazon, as are his seven other books. Signed copies can be ordered directly from Rob here.