As I’ve continued working on Hampton, the 48,000-mile ’73 2002 I bought last fall, I reached the point on the punch list where the most pressing thing was what sounded like a simple driveability issue. On steady throttle at low to mid revs, it hesitated and buffeted slightly—enough to be noticeable. The car started and accelerated fine, so it didn’t seem to be an ignition issue or a fuel-delivery issue, and by the time I had it on the highway, zinging along at 4,000 rpm, the hesitation was diminished. But around town, at 20 to 30 mph, in second and third gear, it definitely didn’t feel right.

Of course, there is no such thing as “a simple drivability issue.” Plus, I’ve had my head mostly in Kugelfischer-injected tii’s for the past fifteen years, and the handful of Weber DGV-equipped cars I’ve owned haven’t had carburetor problems, so if I once had Weber downdraft kung fu, it has largely dried up and blown away.

But still, there are certain bedrock drivability troubleshooting techniques, and if you can’t rely on the guidelines that black plugs and a sooty tailpipe mean that you’re running rich, and gray or white plugs, hesitation on even throttle, and backfiring when you lift mean you’re running lean, then you can’t rely on anything, and might as well resign yourself to an existence created by some badly-treated child of Kafka and Orwell who’s now taking out his gripes with his lot in the universe on you and every other sentient bipedal life form—and who drives a 47-year-old carbureted car. Hell can be very specific.

But there is a saying: “All your carburetor problems are in your ignition.” So I reset the dwell to about 62 degrees and the timing to about 35 degrees of total advance (during which I verified that the timing was actually advancing with increasing rpm).

It made no difference.

I swapped the coil, plug wires, cap, and rotor—basically everything except the distributor, with those from another 2002.

No change

I advanced and retarded the timing by 5 degrees; still no change. It sure seemed like a fuel-mixture problem to me.

Because of Hampton’s low mileage, certain things are original that on most other 2002s have long been thrown into the garbage (or into Creighton Demerest’s neighbor’s pool, for those of us who have read too many “c.d.iesel” posts on 2002faq). One of those is the exhaust-gas-recirculation (EGR) valve, which, under certain conditions, is supposed to send exhaust back into the intake manifold. Although the car’s original two-barrel Solex had been replaced with a Weber DGAV (water choke), other components such as the EGR valve, the little solenoid that actuates it, the charcoal canister, and all of their attendant vacuum lines are still in place. I’m hesitant to remove the EGR valve itself, as its presence is a reinforcing bit of provenance for the car’s low mileage, and because any attempt at removal will likely destroy it; but lean running can be due to vacuum leaks, and this valve and its vacuum lines are prime suspects.

Hampton’s original and still-installed EGR: Sort of like finding fossilized poop in a cave with signs of Neanderthal activity. A sign of authenticity, sure, but… ick.

The little firewall-mounted solenoid with one vacuum line to the intake manifold, the other to the carburetor: Still present, probably inactive, doing lord knows what.

I sprayed carb cleaner around all of these potential vacuum leaks with the engine running and didn’t hear any change in idle. I pulled all the vacuum lines off and capped them, and drove the car. There may have been slightly less hesitation, but if there was a difference, it was minor; the problem certainly wasn’t gone.

The brake-booster hose looked so gnarly that I thought, “How could it not be the source of a vacuum leak?” But I pulled it off and blew compressed air through it with the other end plugged, and was stunned to find it tight.

I disconnected the vacuum line to the distributor and drove with the port plugged up: No difference.

I sucked on the end of the vacuum line, verified that the vacuum diaphragm wasn’t leaking, and that the plate in the distributor actually moved, then reconnected the line.

This likely-original brake booster hose was worn enough to have “I AM A HUGE POTENTIAL VACUUM LEAK” written on it, but capping it made no difference.

Next, I pulled the top of the carb off. I’d removed it last year when I resurrected the decade-dead car, and at that point, to my delight, didn’t find any gummy varnishy residue, only a little sediment. This time I pulled out all of the jets, recorded their sizes, blew all the passageways out with compressed air, and reassembled it.

No change.

I have another Weber DGAV someone gave me years back; it’s been sitting in a box in my basement. I hunted it down, thinking that maybe I’d swap it in. When I found it, I was disappointed, as at best it needed a thorough cleaning, and at worst there wasn’t anything “known good” about it. I pulled all the jets and wrote down their sizes just so I’d know what I had in inventory.

I was glad that I found the Weber in the box in the basement, but it certainly wasn’t a reliable baseline.

Then I read up on the Weber 32/36. If I couldn’t find and fix a vacuum leak, and if I wasn’t willing to pull the EGR plumbing out of the intake and exhaust manifolds for fear of destroying it (at least not yet), and if the Weber’s float level was set high enough that the holes into the internal passageways were covered with fuel (it was; they were), then the next most likely issue was that the idle circuit, which controls not only idle but the transition to mid-throttle, was running too lean.

I thought, boy, it’d sure be nice if I had an oxygen sensor installed in Hampton’s headpipe and an air-fuel meter on the dash, as I had in my tii when I was troubleshooting its seemingly intractable lean-running issues. But again, this wasn’t a car I wanted to drill holes into, cut up, or modify.

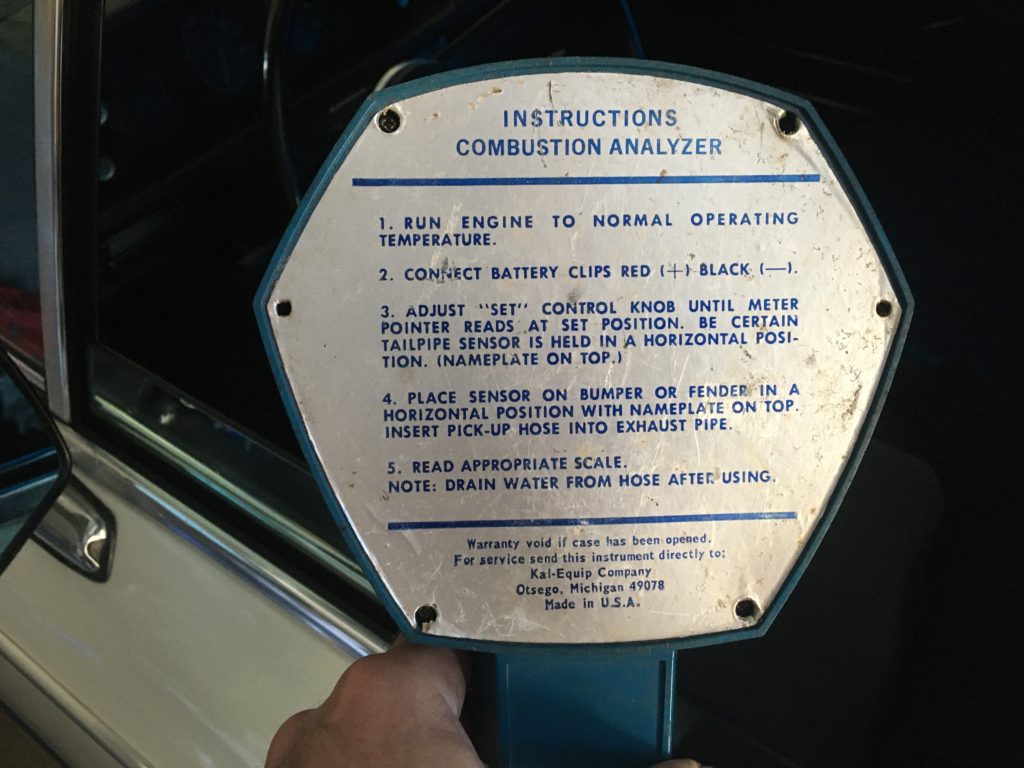

Then I remembered that I have a “Kar-Check” portable exhaust-gas analyzer. I bought it in a pawn shop in Austin, Texas, in 1983. You have to power it off the car’s battery, and run a thick wire that goes to a tailpipe probe. I haven’t used it much in recent years. I recalled that it was functional, but was challenging to cajole the tailpipe probe into staying in place; it didn’t have the immediacy of the reading of an AFM, and it tended to drift, requiring re-zeroing.

Still, something was better than nothing.

Instructions on the back of the “Kar-Check” exhaust-gas analyzer. I don’t own a kar. I hope it works on a car.

I dug it out and tested it in the garage. My memories all were accurate, except that I’d forgotten that I’d wired in a cigarette-lighter plug so I didn’t have to stretch wires with alligator clips to the engine compartment. Before I even left the garage, the analyzer confirmed that the car was idling rich, but that when I slowly revved it, it leaned out, although it wasn’t swinging off the scale, or even as far as the ideal stoichiometric 14.7:1 ratio. As I said, its readings aren’t as accurate or as immediate as an oxygen sensor and an AFM gauge, but it did give me basic near-real-time feedback.

I first tried simply making the idle mixture richer with the mixture adjustment screw. I could see the effect at idle on the meter, but it didn’t seem to have much if any effect on the low-mid-rpm hesitation.

Then I drove the car with the analyzer in place. When I put my foot into the gas, I could see the needle swing rich as the accelerator pump did its thing and squirted raw gas down the primary throat, but as the acceleration flattened out and the car went back to an even throttle, the needle swung lean and the hesitation returned.

The exhaust gas analyzer swings lean at even throttle.

So I did what I often do: I ordered a few things so I’d have them queued up to try. The first were some larger idle jets. A web search took me to Pegasus Auto Racing, whose site clearly identified the fact that on a Weber DGV, the primary idle jet that sits behind the solenoid cut-off switch is a different part than the secondary idle jet. The one that was in the car was marked as a size 60, so I ordered a 65 and a 70.

The other things I ordered were the two bits necessary to remove the EGR and block off the manifolds so I could have them on hand if I decided that that was necessary. A round block-off plate for the intake port was orderable for about $30 directly from bmw2002faq.com. I was already familiar with the block-off for the exhaust port, because I recently had to do this on Bertha, my ’75 2002, when I broke its 35-year-old HeaderCraft exhaust headers and had to replace them with a conventional exhaust manifold and downpipe. The thread for the removed EGR pipe is M16x1.5, which happens to be the same as the oil-drain plug on a 2011–2019 Subaru Forester (and probably other models).

The idle jets arrived a few days later. I swapped in the size-65 jet, and again jury-rigged the exhaust-gas analyzer probe to hang off the rear bumper and in the tailpipe.

The exhaust probe is zip-tied to the bumper.

If there was a difference, I couldn’t feel it or see it on the analyzer; the car still hesitated and the needle still swung lean. Damn.

Having recently resurrected Bertha and her dual-Weber 40DCOEs that had sat for 26 years, and the Lotus Europa and its dual Zenith-Strombergs that had sat for 40, and doing nothing other than cleaning the sediment out of the float bowls, blowing out the jets, lubricating the shafts, and putting them back together, I’d become cocky. I now began thinking that perhaps my luck had run out, that Hampton’s decade-long snooze had had detrimental effects on the Weber, and that perhaps some internal passage was plugged and ten seconds of poking and prodding it with a compressed-air nozzle wasn’t going to be good enough. In the old days, I’d rebuilt carburetors, dutifully buying the gallon of Berryman’s B12 Chem-Dip—the nuclear-powered stuff that comes with the little basket—stripping the carb, letting it sit for days in the disgusting Grey Poupon-colored muck that, these days, if it spilled, would cause a hazmat team in moon suits to descend on your house and lop fifty grand off your property value, reassembling it, and never being satisfied with the result. I didn’t want to “rebuild” the damned Weber; I just wanted to bolt something on that solved the problem.

I began looking at used Webers on Facebook Marketplace and Craigslist, but of course you run into the same “known good” issue as with the one that was already on the car and the one in the box in the basement. New DGVs are about $230, which wasn’t out of the question if it fixed the problem—but I didn’t know if it would.

And then I remembered that I still had one larger jet (size 70). I almost didn’t try it, since everything I read said that the jump from a 60 to a 65 was already pretty substantial, but what the hell: In it went. Around the block I went.

Not bad. Not bad at all.

Although there wasn’t a dramatic difference in the reading on the exhaust-gas analyzer—the car was still swinging lean at steady throttle, at least leaner than idle—the hesitation was substantially less than before I put in the bigger jet. At times it was good enough that it probably wouldn’t have jumped out at me as a drivability issue.

I freely admit that it’s quite possible that the larger idle jet is compensating for some other issue, such as a vacuum leak. I’ll live with it for a week and decide whether it’s good enough or whether I need to pull the EGR valve and plug up the manifolds. But here’s hoping that the lean times really are over.—Rob Siegel

Rob’s most recent book, Resurrecting Bertha: Buying Back Our Wedding Car After 26 Years In Storage, is available on Amazon here. His other books, including Just Needs a Recharge: The Hack MechanicTM Guide to Vintage Air Conditioning, are available here on Amazon. Or you can order personally-inscribed copies of all of his books through Rob’s website: www.robsiegel.com. His new book, The Lotus Chronicles, will be available in the fall.