Last week, I wrote about the tendency some 2002-advice-dispensing folks have to reply to every thunk, clunk, and rattle-related inquiry with the blanket response “It’s the bushings.” In the piece, I explained that the term “bushing” is usually reserved for circular or cylindrical rubber components with a hole through the middle, but there are other similar components that are part of the same vibration-isolation context. I then stepped through all of the suspension and steering bushings in a 2002 (any pre-E30 BMW will be similar), and the end, I breezily said “Unless you want to get into minutia such as the rubber bushings that secure the air cleaner on a carbureted car, or the ones that isolate the electric fuel pump on a tii, that’s it.” However, the more I thought about it, the more “bushings” and related items I kept coming up with.

So, today, I thought I’d augment the tour of Bushingville by looking at other non-suspension bushings as well as other components that, while not technically bushings, perform similar vibration or noise isolation duty.

DRIVETRAIN-RELATED ISOLATION

There are a fair number of rubber bushing-like items whose job it is to either isolate drivetrain vibrations from coupling into the chassis, or allow motion of the drivetrain on the chassis, or both. Let’s step through them front to back.

Engine mounts are present on the left and right side of the engine, supporting it on the front subframe. Technically, they’re not bushings, as they’re blocks of rubber with threaded posts protruding from either side to support weight rather than having a hole through the middle to allow motion, but they perform a similar role to bushings in both vibration isolation as well as allowance of motion. Engine mounts can either dry out and crack, or become soft due to heat and leaking oil. The tell-tales of bad engine mounts are the engine rocking excessively side-to-side during starting or revving, or rocking fore-and-aft on braking.

The driver-side engine mount on a 2002.

And the passenger-side engine mount.

The transmission mount, like the engine mounts, is a block of rubber with threaded posts protruding out both ends (or one threaded post and a hole for a bolt). It supports the back of the transmission on a cross-bracket. Due to the tendency of old transmissions to leak fluid out the selector shaft seal, it’s very common for this mount to nearly dissolve into goo. Wear or degradation rarely causes noise. Instead, the effect is more that, when you’re under a car, you put your hand on the hot-licorice-like transmission mount and go “ICK! I can’t believe this is still working!”

The incredible shrinking transmission mount: Left is the original degraded-into-nearly-nothing 2002 mount. Right is the E21 320i mount it’s usually replaced with.

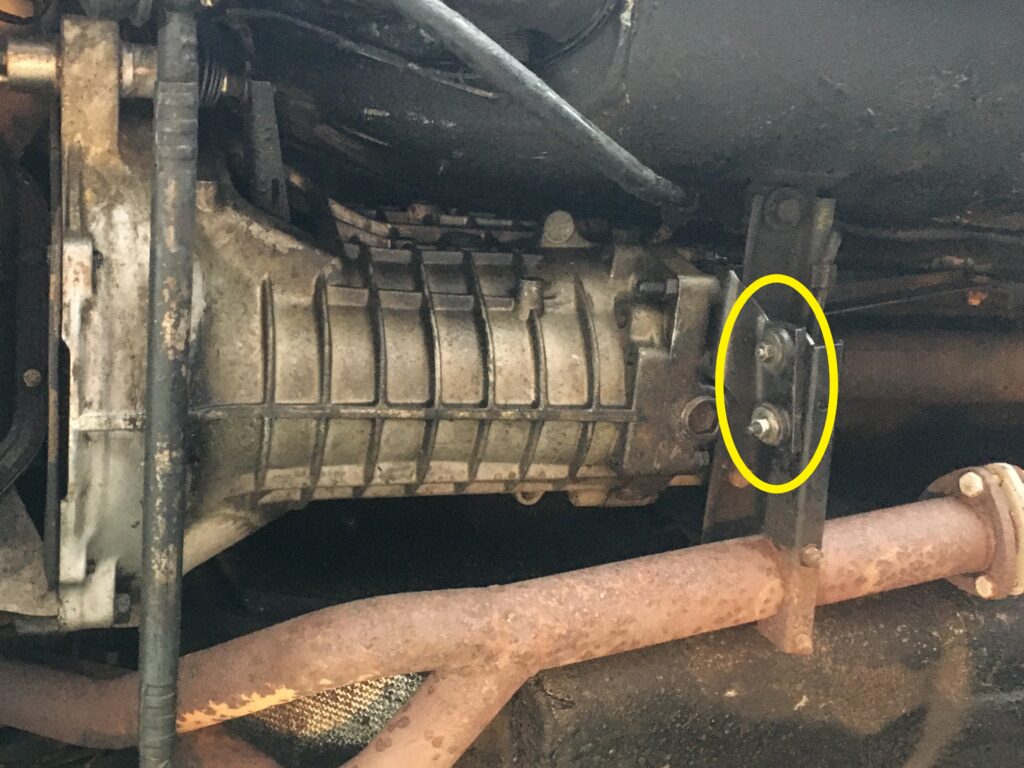

This shows the transmission mount in place on the cross-member.

As I look at the photo above, I realize that there are several bushings related to the shift linkage, but I think I’ll break that into a separate piece.

The Giubo: It would be a rare do-it-yourselfer who owns a 1970s-era BMW and does not know about the giubo—the bagel-sized rubber flex disc that sits between the transmission output flange and the driveshaft input flange—as a) it’s always been a normal-wear-and-tear part, and b) it announces its need for attention in a loud and specific manner. Although the giubo’s form factor is having eight (or six, depending on the model) metal sleeves all sharing a rubber housing, sort of like eight bushings living together in a rent-controlled apartment, it’s less a vibration-isolation component than a motion-allowing component. That is, its purpose is to maintain the coupling of the engine to the driveshaft as the engine moves on its mounts. When giubos crack, the first symptom is usually a loud whumping under the transmission tunnel under acceleration. If the sound is ignored, the unintended motion can progress to the point where the rotating bolts tear into the back of the transmission, causing all sorts of damage.

(As an aside, yes it’s spelled “giubo,” not “guibo,” and yes, technically, it’s pronounced “GEE-bo,” but by mutual agreement years back between me and Satch Carlson, Roundel usage is that we spell it “guibo” but pronounce it “GWEE-bo,” because, well, it’s funnier.)

This giubo, in a car that had been sitting for a decade, was visibly cracked.

This is what it looked like when removed.

The driveshaft center support bearing is a vibration-isolation component that hangs the middle of the driveshaft—just in front of its universal joint—from the underside of the car via a rubber shroud with a bearing race in the middle. If the rubber shroud has deteriorated from age, or there’s rumbling coming from the middle of the driveshaft, the assembly (the center support bearing and its attendant shroud and bracket) should be replaced.

You can see how badly deteriorated the rubber on this center support bearing is.

Replacement of the center support bearing is a real pain, requiring heat and lots of leverage.

Two differential carrier bushings are pressed into the differential carrier (the bracket from which the back of the differential is hung) and bolted to tabs welded to the underside of the car. I don’t consider them a normal-wear-and-tear item, but if they’re completely worn out, they can cause metal-to-metal contact and create a banging that, as with worn-out engine mounts, is sometimes apparent on acceleration as the torque from the twisting driveshaft causes the carrier and the differential to move.

The differential carrier bushings.

ALTERNATOR BUSHINGS

I’ve written many times about “The Big Seven” things likely to strand a vintage car. One of them is belts. On modern cars, there’s typically a serpentine belt that runs multiple components, and a series of idler pulleys and tensioners that route the belt and automatically keep it tight. Thus, “belts” is not only the belt, but these related components, without which the belt can be thrown. On a vintage car like a 2002 , there’s typically just one belt—the fan belt that drives both the alternator and the water pump. Its tension is manually adjusted by swinging the alternator on its pivot point and tightening the bolt holding it to the adjustment bracket. Thus, there aren’t tensioners and idler pulleys to fail like on a modern car.

However, there are three separate sets of vibration-isolation bushings on the alternator, and when they fail, they can cause a surprising number of problems. The largest is the pair that’s pressed into the alternator’s pivot point (the part that’s mounted in a bracket bolted to the engine block). When these bushings get mushy with age, it causes the alternator to cock forward under the tension of the fan belt. If the bushings deteriorate past a certain point, the belt won’t stay tight and the alternator and more importantly the water pump stop spinning, resulting in overheating and loss of charging. Pressing the two bushings out, cleaning out their recess in the alternator, pressing in the new nylon or Delrin replacement bushings, and getting the circlip holding them back on can be a bit of a pain.

Bushings in the alternator pivot point. This one is worn to the point where it’s been pushed off-center.

The main bushings on a 2002tii alternator reduced completely to goo.

A re-bushed alternator pivot point.

The second alternator bushing is a similar but shorter one pressed into the ear on the alternator where the tensioning bracket attaches. Like the larger pivot bushing, it’s held in with a circlip.

The smaller bushing on the alternator’s tightening ear.

The third is a pair of bushings on the pivoting base of the tensioner bracket. These are thin metal-and-rubber parts, about the size of a quarter, with a ridge that snaps into the hole at the end of the bracket.

EXHAUST

I was hesitant to bring the exhaust into this, but it makes sense, as there’s no question that there are rubber components that isolate its noise from the chassis of the car.

Two rubber bushings on the exhaust support bracket provide exhaust vibration isolation to the strain-relieving connection of the back of the downpipe to the back of the transmission. When these bushings deteriorate, as they inevitably do from leaking transmission fluid and heat, the bolts and metal sleeves can contact the metal bracket and raise a hell of a racket.

The bushings on the exhaust support bracket.

Of course, the muffler is supported by its rubber hangers. I don’t really think of these as bushings, as they’re not pressed or clamped into anything, but they perform a similar function of both motion allowance and noise isolation. If they’re loose or they fail, the exhaust can bang, and if they’re replaced with chicken wire or a hose clamp, exhaust noise and vibration can couple into the body of the car.

One of the rubber exhaust hangers on a 2002.

Next week, I’ll wrap this bushing stuff up with a piece on the 2002’s shift linkage.—Rob Siegel

____________________________________

Rob’s newest book, The Best of The Hack Mechanic, is available here on Amazon, as are his seven other books. Signed copies can be ordered directly from Rob here.