One of the things in life that bothers me is a lack of precision in description. After years of training, my family knows never to simply say, “The car won’t start,” because that’s an imprecise and useless description of a problem. I’ll immediately sigh and say, “Did it crank? Did you hear the starter click and spin? Did it spin quickly or slowly? Did the dashboard lights come on?”

Similarly, it drives me crazy when I read a post on some forum about someone’s 2002 that’s making thunking or clunking noises over bumps, and someone replies, “It’s the bushings.” Or when someone is looking for advice on buying a 2002, and a reply is, “Make sure to find one where the bushings have been replaced.” Or when someone has just bought a 2002 and is asking for advice on what to replace or upgrade first, and someone says, “The bushings.”

You get the idea.

The thing is, if you’re buying an old car like a 2002, what you want is a tight car, one that has a minimum of thunks, clunks, and rattles, and one whose steering has as little play as possible. While certain bushings may be causing or contributing to these problems, so many other things contribute to noise and a lack of tightness that repeating this mantra of “it’s the bushings” is actively misleading.

When spoken of in the context of suspension work, a bushing is a flexible vibration isolation component, usually rubber, usually sitting between two pieces of metal (one of them is often a bolt), and usually having a hole through the middle with a metal sleeve in it. A 2002 has the following suspension bushings:

FRONT

- Two strut-tower bushings

- Two radius-arm bushings

- Four control-arm bushings

- Two sway-bar clamping bushings and eight sway-bar end-link bushings

REAR

- Two shock-tower bushings

- Two subframe bushings

- Eight trailing-arm bushings

- Sway-bar bushings like the front

The thing is, if a 2002 is making a thunking or clunking sound over bumps, sure, it could be due to one or more of these bushings, and if the steering has play in it, it’s possible that it’s due to some of the front bushings—but either of these problems could also be due to any number of other things.

But this is the bushings column, so let’s give each of them its due.

The two front strut-tower bushings (also colloquially called hats due to their appearance) are rubber assemblies with a ball-bearing race in the middle of a metal plate with three studs that mounts to the underside of the front fender well. The bushings sit on top of the front MacPherson strut assemblies, allowing them to turn in response to steering input.

The strut cartridge’s piston comes up through the bearing and is held there with a nut. It and the bushing assembly keep the spring under compression. The presence and sequence of a series of washers and spacers is essential for allowing the bearing to turn, and for the bushing assembly to function without banging. A domed rubber dust cap sits on top to keep dirt out of the bearings.

It’s common for the rubber in the bushing to crack with age. If it fails completely, the strut piston can break through and hit the underside of the hood. In addition, the bearing can fail, creating noise. Thus, these bushings are a prime place to check if there’s a sharp metallic noise from one side of the front of the car over bumps—but such a noise can also be due to a loosening of the top collar nut holding the strut cartridge in its housing, or from another suspension or steering component.

A cracked strut-tower bushing.

The two front radius-rod bushings (also called tension-strut bushings) are peach-size rubber bushings in the two big holes in the most forward part of the front subframe. The radius rod (tension strut) goes through them; the rod acts as a fore-and-aft brace for the control arms. With age, heat, and exposure to oil, these bushings can crack and flake, or can turn into rubbery goo. In extreme cases, it’s possible for these bushings to be so deteriorated that the tension strut bangs around, but usually, wear allows excess movement of the tension strut. This is sometimes felt as a squirrely feeling on hard braking. They can be removed and installed fairly easily using a large pair of slip-joint pliers, but some folks press them in and out using a C-clamp or a threaded rod.

One of the radius-rod bushings: This one is old but completely intact.

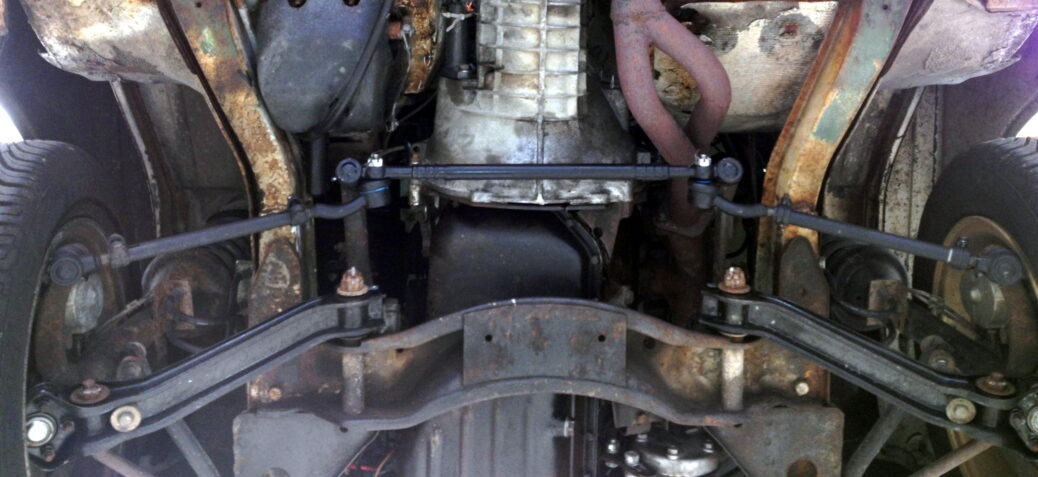

The four front control-arm bushings are pressed into the inner and outer ends of each control arm. The inner ends are attached to the front subframe with large bolts, allowing the control arms to pivot when the springs and struts allow the wheels to move vertically. The outer bushings receive the back end of the radius rods. All four need to be pressed in with a press, a C-clamp, or threaded rod. Like the radius-rod bushings, they can crack or get gooey. As they can affect the front wheel alignment, you want them to be firm. The one shown in the photos below isn’t in good condition, but neither this nor the other control arm appears to be moving, so I haven’t replaced them.

One of the inner control-arm bushings shown from the rear…

…and from below, where it’s attached to the front subframe.

The ten front sway-bar bushings are different from the ones above in that they have no metal sleeve. There are two U-shaped clamps that hold the sway bar to the tops of the front subframe; inside those clamps are the sleeved rubber bushings. They’re slit so that you can slide them around the sway bar and then put the clamps over them. The rubber units often last the life of the car, but in extreme cases they can wear through allowing the sway bar to rattle, or bang against the clamp or the subframe. The clamps are held on with bolts with 6-mm Allen heads on the bottom and nuts on the top. They can be a bit of a pain; when installing thicker sway bars, it is often maddening to get the clamps back over the bushings and far enough down that the bolts go far enough through the holes to get the nuts on them. I’ve squeezed the clamps down with slip-joint pliers.

Long bolts go through the metal eyelets at the ends of the sway bar, securing it to the control arms. At the tops and bottoms of the bolts are a pair of little sleeveless bushings that allow the bolt and the nuts on the end to be tightened and the sway bar to move as the control arms go up and down. There are two on the top and two on the bottom, on both sides, for a total of eight. These aren’t pressed into anything, so they’re trivial to remove and install.

One of the front sway-bar bushings and the clamp holding it.

The two little rubber donut bushings at the top of the sway-bar end link: You can see one of the two on the bottom where the bolt passes through the lower control arm.

Extra credit: Idler arm bushing: I said I was going to talk about suspension bushings. The idler arm bushing is part of the steering, not the suspension, and it doesn’t fit my definition of a bushing as a rubber anti-vibration component, but I’m going to include it because it showcases the very issue I’m trying to raise about there being many components that affect a car’s tightness. 2002s don’t have rack-and-pinion steering like modern cars; they instead have a steering box on the left side of the engine compartment. An arm comes down from the box and connects to the center link (also called the drag link). On the right side, the steering box arm’s movement is mirrored by the idler arm, which pivots on a nylon sleeve referred to as the idler bushing. Replacing it is a pain, as the nut holding the idler arm must be removed, the arm slid out, the bushing driven out of its recess, and a new one driven in. But if this bushing is worn out, it can be the source of both banging and steering play.

Removing the bolt holding the idler arm.

The two rear shock-tower bushings are slightly cone-shaped rubber bushings that snap into the holes at the tops of the rear shock towers (the rear fender wells). A metal sleeve goes through the middle of the bushing. The top of the shock absorber goes through it, flanked by washers. If the bushing wears out, the metal sleeve can contact the shock-tower housing and make a metallic banging. If the whole thing simply becomes loose, you can hear more of a dull thud. Removal and installation of the bushing can often be done by hand.

A rear shock-tower bushing with the top of the shock protruding through it.

The two rear subframe bushings, as their name implies, hold the rear subframe to the body of the car. They’re about the size of soup cans, and have a metal cylinder on the outside with an integrated bracket that bolts onto the rear subframe. Inside the housing is a rubber bushing with a sleeve. A bolt comes down through the sleeve from under the back seat. The entire housing, bracket, and bushing are generally replaced as a single unit, but I believe that there are sources for just the internal rubber (or urethane) bushing if you want to press the old one out. It’s possible to replace these bushings without removing the subframe, but to do so, you need to drive the central bolt upward, which isn’t easy because the top of the bolt is a tapered splined fit, and after 50 years, it doesn’t want to come out.

A rear subframe bushing shows the integrated bracket (on the left side of the metal housing) where it bolts to the subframe.

The eight rear trailing-arm bushings are in the two joints holding each of the two rear trailing arms to the rear subframe. At each attachment point, a pair of bushings are installed, with one pushed in from the left side, the other the right. Because of this, they generally don’t require a press like a tightly fitting bushing, such as used on the radius rod or control arm, where the bushing has lips on both ends.

The left rear trailing arm attached to the subframe: Yellow ovals show the two attachment points. (Not my car. You can tell, right? Powder-coated components. )

Closeup of one of the four pairs of rear trailing-arm bushings.

It is difficult, but not impossible, to unbolt the rear trailing arms from the subframe, tip them, access the bushings, push the old ones out, and install the new ones. However, most folks (including me) advise that the better approach is to drop the entire rear subframe as a unit and replace all the bushings—meaning the two rear subframe bushings and the eight rear trailing-arm bushings. Many people combine this with sandblasting and powder-coating the subframe and trailing arms. That’s not my jam, but you do you.

Because the rear bushings are further away from the heat and oil of the engine, I’ve never seen them get gooey and as badly deteriorated as the radius-rod and control-arm bushings in the front can get; I’ve only seen them crack. And even then, I’ve never seen them get so bad that they’ve been the primary cause of an annoying thunk or clunk. This is part of my energy behind pushing back against the whole “It’s the bushings” thing.

The ten rear sway-bar bushings are essentially identical to those on the front.

Unless you want to get into minutia such as the rubber bushings that secure the air cleaner on a carbureted car, or the ones that isolate the electric fuel pump on a tii, that’s it.

A word on urethane bushings: In my humble opinion, don’t (okay, that’s five words). All of the bushings listed were originally rubber, and most of them, with the possible exception of the front strut-tower bushings, are now available in polyurethane. Urethane bushings are harder and less compliant, and they tend to squeak. I’ve never used them for anything other than thicker aftermarket sway bars, and there, only because there appears to be no choice; beefier sway bars usually come with urethane bushings for both the clamps and the ends. The urethane bushings at the ends are fine, but the ones under the clamps eventually squeak over every little bump unless they’re lubricated at regular intervals. I absolutely despise them, but I’ve looked for a source of rubber bushings for 22-mm front sway bars and have never been able to find them.

Conclusion: Sure, have a look at the bushings. And if any of them are awful, replace them. But there are so many things on a 5o-year-old car that can thunk, clunk, and rattle that intoning, “It’s the bushings” is unhelpful; it’s the “That’ll buff out” of noise advice. I’ll say it again: If you’re sorting out a 2002 you just bought, or are looking to buy one, really, what you want is a tight car, and that’s a function of steering components, shocks and struts, springs and their rubber perches, nothing in the engine compartment banging, all the trim, bumpers, grilles, and mirrors being held on securely, the little 90¢ door-lock rod grommets not being worn out, the doors and trunk shutting securely, and on and on.

So the next time someone on a forum says, “It’s the bushings,” challenge him or her. Ask, “Which ones?”—Rob Siegel

____________________________________

Rob’s newest book, The Best of The Hack Mechanic, is available here on Amazon, as are his seven other books. Signed copies can be ordered directly from Rob here.