The older we get, the more things run together. I’m sure I’m not alone in feeling like the major stages in my life can be divided into elementary school, junior high, high school, college, and the rest of my life—which feels like an equally-accessible set of scenes of everything since college (which, by the way, still feels like last week, even though I now make noises like an old man every time I get up).

I could try to use cars to mark the passage of time, but that doesn’t really work very well, at least not with my cars. There have been too many of them (the BMW count is now nearly 70). It works better with Maire Anne’s cars, because those were the family haulers. There was the VW Westfalia camper we brought up from Austin with us (the degree to which it was unsuited to haul a baby in a car seat wasn’t really apparent until we tried to use it that way). There was my 1983 E28 533i that I tried to make work as a family car until the form-fit rear seats swallowed one of my kids’ butts like a taco. There was the 1983 Volvo 245 GLT wagon that wasn’t a bad compromise until Child #3 was born; I tried to demonstrate to everyone that sitting in the rear-facing third seat would be fun, so I parked myself there for a few miles while Maire Anne drove, and I emerged a pale shade of greenish white, saying, “We’re buying a minivan.” (Maire Anne laughed: “That was all I needed to do to get you to buy a minivan?”). There was the Toyota Previa five-speed, which we both loved but which was far from the Toyota maintenance-free ideal. There was the Mazda MPV, the acceptable but sad admission that minivans with row-your-own standard transmissions were no longer available.

The one big automotive constant across my decades has been the BMW E9 3.0CSi. Purchased in 1986 as someone else’s failed body-and-mechanical project, revived with new sheet metal attached in ’87, repainted Signal Red in ’88, it has been the black hole around which everything in my automotive galaxy revolves. It’s been around longer than any of my kids, it’s had multiple road trips to the Vintage and other events (these are the things that really burn a car into our memory), and it’ll be the last non-daily-driver I own before I die or the creditors beat down the door, whichever comes second.

The E9 is funny, though, because it was straddled by 2002s—one of them the same 2002. That is, I began my BMW life as a 2002 guy; I had a bunch of them in Austin, moved back to Boston with Bertha the ’75 2002, and had a bunch more 2002s before I bought the E9. Then, when we moved to Newton, the new house’s one-car garage had room for only the E9, so the 2002s, including Bertha, had to go.

As I have written, I sold Bertha to my friend Alex, then bought the car back 26 years later. But in the interim, there were nearly fifteen years when any other car I owned had to sit outside, so I didn’t own a 2002. I love the fact that, once the garage was built in 2005, I began buying 2002s again, and reclaimed my history as a 2002 guy almost without missing a beat—but the fact that Bertha came, went, and came back makes her sort of like an old college friend you lost touch with for decades and now see a few times a year to enjoy your shared history, even if the conversations have lost some of their snap.

But to my surprise, the second-most-long-lived car in the stable isn’t a 2002; it’s the 1999 Z3 M coupe. I just now looked at car’s title: I bought it in 2007 (I would not have predicted that). But when I saw the date, some things came back to me.

In 2005, while I was in the process of finally building a new garage here in Newton, the privately-owned company I’d worked at since 1984 was acquired by a behemoth defense contractor. I convinced myself that as long as I kept writing proposals that funded my own work, I was still in control of my destiny. And it worked—for a while.

I still had my ’82 Porsche 911SC Targa. When the garage went up, I bought my first 2002 in fourteen years, a ’73 tii. I could shoehorn one more car into the new garage over the winter. It wasn’t that I’d been lying awake and lusting after an M coupe, which was a much newer and much more expensive car than I was used to buying; it was more, I think, a subconscious slow burn.

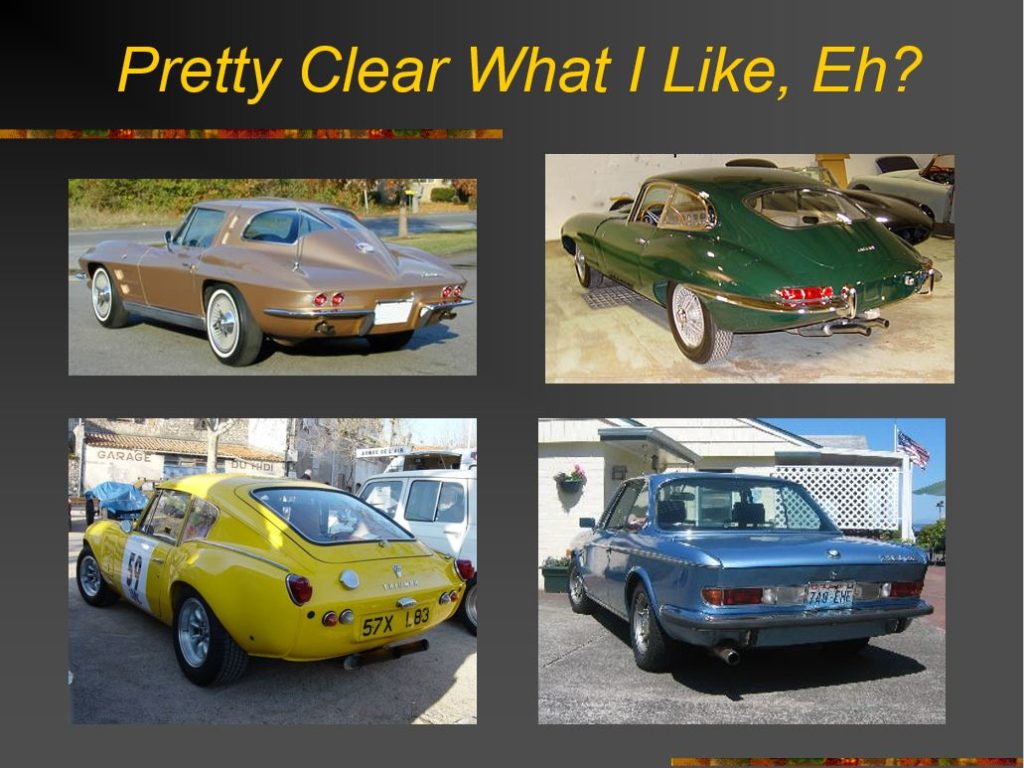

I remember putting together my first CCA chapter talk to give in Memphis, Tennessee. I talked about how I have lusted after cars from the time I was five years old and could recognize cars like split-window Corvettes and E-Type Jaguars, and how I bought my first car, a Triumph GT6+, because it looked like a little E-Type. I combined those with the E9 I owned, and concluded that what they shared was that they were all great watch-them-drive-away cars.

I like interesting butts and I cannot lie.

The obvious extrapolation, or so I said, was that the next car would be an M coupe. I even included a slide about it in the presentation.

It was apparently my destiny.

But really, I was kidding. It wasn’t anything I’d lie awake obsessing about.

Then, however, I saw an M coupe with a $14,500 asking price in The WantAdvertiser, back when looking for cars by reading ink printed on pulp was still a thing. The car was on the Massachusetts-Rhode Island border. I drove down there the snowy cold dead of winter 2007 to check it out. It was a ’99 (S52 engine), silver with a black interior. The owner seemed an unlikely guy, a financial analyst in Boston who was not a CCA member and who did no high-performance driving events. He’d bought the car because he fell in love with the shape, and daily-drove it 4o miles each way into Boston’s financial district. It was not a great winter car, however (like, duh), so he’d just signed a lease on a new E90 328xi.

The M coupe looked great, and mysteriously had an AC Schnitzer badge on the back that he knew nothing about. But he warned me that it had bent wheels and blown shocks.

The just-purchased M coupe rests in the recently-built garage.

A few weeks ago, I wrote about the taxonomy of automotive passion, and spoke of how if you encounter a car whose exterior lights your fire, and that excitement continues into the interior, and when you drive the car, you love it and connect with it at the gut level, you get hooked hard. This is exactly what happened with the M coupe. The silver trim rings around the dashboard instruments and the oval rear-view mirror were unexpected retro design elements that meshed beautifully with the largely traditional BMW dashboard. I piloted the car carefully to the nearest highway, got on the entrance ramp, and mashed the accelerator pedal: Bent wheels, seized shocks, and all, I found myself doing 90. My reaction was immediate and visceral: Oh my god oh my god oh my god I am going to do whatever is necessary to buy this car.

We agreed on $12,500. I wound up taking out a bank loan, which was unheard of for me. I was a nervous wreck during the two weeks it took for the paperwork to go through, thinking that someone was going to steal my M coupe out from under me.

None of this made any sense. The M coupe and the 911SC were, in certain ways, similar cars; owning both at the same was ridiculous and unjustifiable. Except that that’s what I wanted to do, and now I at least had the garage space to do it.

As a bit of money freed up, I paid off the loan. I never found anything in the car that justified the AC Schnitzer badge, but it was part of the mystery of the car, so I left it on there. Silver with a black interior is, I believe, the most common color combination for M coupes, and thus it gets dissed and downrated as part of a desirability scorecard, but in my opinion, the car’s shape is so unusual that it doesn’t need to be pumped up with a zingy color, and silver downplays and de-accentuates it in a very effective way. The same is true of the black interior; I’m sure that if I had a Dakar Yellow car with a matching two-tone black-and-yellow interior, I’d love it, but silver/black is just a very easy color combination to live with.

I loved this dashboard and console from the get-go.

I used the M coupe as a daily driver for the 4.5-mile commute I had for several years, but when Massachusetts changed its insurance-related laws, allowing cars that were newer than 25 years old to go on an agreed-value classic-car insurance policy, I put the M coupe on my Hagerty policy along with the E9 and the 911SC in order to save money. Officially, that meant no more commuting to work in it. The car had 95,010 miles on it when I bought it. It now has 106,612. So I’ve put 11,602 miles on it in thirteen years—not a lot of use.

One of the reasons the car has been so lightly driven is that when I took it from Boston to New Jersey for a business trip almost ten years ago, I discovered that the bolstered seats that look so supportive are in fact too stiff; the foam on both the seat base and seat back don’t conform to my back the way the vintage Recaros in my 1970s cars do. Unless I use Tempur-Pedic pillows both behind my back for lumbar support as well as under my butt for comfort, after two hours of driving, I’m in a lot of pain. And the heavily bolstered nature of the seats makes it kind of awkward to use two pillows—not like in my Bavaria, where the big, flat burgermeister seats give you lots of room for them. For this reason, the car hasn’t seen the kind of epic road trips that the 2002s, the E9, and the Bavaria have.

These seats are, surprisingly, a problem. At least they are for me.

But I do absolutely adore the car. With that oft-photographed fat planted butt, it’s a look-back-at-it-after-you-park-it car, as any car that you love should be. And it’s completely unlike anything else I own—or have ever owned. Its 5.3-second zero-to-60 time may be tame by modern standards, but it feels blazingly fast to me; it’s certainly as fast as I ever need a car to be.

Due to the car’s inheriting the E30’s trailing arms instead of the E36’s central-link rear suspension, the handling doesn’t have the head-into-a-curve-too-hot-and-it-autocorrects-for-you feature. Instead, hard cornering requires attention; the rear end is certainly capable of coming around if you head into an entrance ramp too hot. The suspension is stiff without being molar-jarring. The shifter is so tight it spoils me when I drive the vintage cars.

As long as I’m not in the car for hours at a stretch, it’s always an absolute blast to drive. I may have never taken the car on a proper road trip, but there is one straight stretch of Route 2 on the way back from Fitchburg where, in 45 years of driving it, I’ve never seen a speed trap, and I do briefly wind up the car there to license-suspending speeds I would not attempt in any of my other cars.

I never cease to be astonished by how little the car really is. Like the Z3 roadster it’s based on, the M coupe’s length is 158.5 inches, barely over thirteen feet. That’s eight inches shorter than a 1972 2002. Its diminutive size is beaten only by my Lotus Europa, which is one inch shorter and even lower.

I swear that this is an unretouched photograph.

The Lotus is more exotic, but there’s no question that the M coupe kicks its butt in every measure.

Maintenance-wise, the M coupe has needed very little. After I bought it, I had the wheels straightened and put Bilsteins at all four corners. The driver’s-door window regulator also needed to be replaced. A few years later, just to be safe, I did the full-on prophylactic assault on the cooling system, replacing the radiator, expansion tank, thermostat, water pump, and all major hoses. In 2010 the throwout bearing began acting up, necessitating a clutch replacement, which was a pain. A few years ago one of the calipers started seizing, so I rebuilt it.

My main complaint about the car is that, even after rebuilding it, the glove box is a source of minor rattles. But that’s pretty much it.

The cars all get moved around quite a bit between the spaces in my garage at the house and the four spaces I rent in Fitchburg, 50 miles west of here. Vehicles I plan to work on gravitate to the house. Because the M coupe is both the newest of the enthusiast cars and the one in the best condition, its needs are minimal, so it often sits out in Fitchburg for months.

I go through waxing and waning stages of infatuation with many of the cars. The Lotus got and continues to get a lot of my attention since I roused it from its 40-year-sleep eighteen months ago. It’s one thing to resurrect a long-dead car, but quite another to resurrect it so it performs like, well, like a Lotus, and doing so has been unbelievably satisfying.

The suspension refresh in Louie the ’72 tii, and the long drive I took in it on the Nor’East 02ers Jeff Taylor Memorial Tour, further cemented my relationship with that car. I hadn’t spent much time with the M coupe over the past few years, and when I find myself not using a car, I ask myself questions about whether I should keep it. I flirted with selling it several times (I have a Facebook friend who is relentless in his reminding me that he has dibs). M coupes have been on many lists of sure-fire appreciating classics, but my car’s value, as a silver/black ’99 S52 daily driver with 106,000 miles, wheels in need of refinishing, and a few quirks from its two previous owners, is never going to command the big money that low-mileage S54 cars are bringing; it’s market value is probably under twenty grand.

Still, in these times, who couldn’t use twenty grand?

What’s kept me from putting it up for sale has been the fact that when I sold my 911SC ten years ago, three months later the value of air-cooled 911s went crazy, and I’m convinced that the same thing will happen if I sell the M coupe.

I’ve recently had a short-term space crunch due to my keeping a friend’s ’73 tii in my garage while I help him sell it on Bring a Trailer, which required me to move the cars around. About a month ago, I brought the M coupe back from Fitchburg to free up a garage space out there, because it’s the one normally-garaged car that can sit outside in the driveway in Newton for a few weeks without my feeling like I’m committing an oxidation-related automotive crime. So it’s been here for me to take for pleasure drives and for running errands.

To absolutely no one’s surprise, I’m in love all over again. There’s a reason why I’ve kept the clown shoe for thirteen years while dozens of other BMWs have come and gone. It’s a unique car that deserves all of the hype that’s been slathered on it. As I wrote in the January 2008 issue of Roundel, “I now can say without hesitation that this is a vixen of a car, a dirty mistress who sticks her tongue in your ear and unbuttons your trousers in full view of polite company and doesn’t care.”

Screw the expectations of value. They’re no longer a factor in whether or not I keep the shoe. It’s simple: I love this car. It’s staying. Maybe I’ll spray its entire interior with Tempur-Pedic foam and drive it to Banff with Maire Anne. Now, that’s something I’d remember.—Rob Siegel

Rob’s latest book, The Lotus Chronicles: One man’s sordid tale of passion and madness resurrecting a 40-year-dead Lotus Europa Twin Cam Special, is now available here on Amazon. Signed copies of this and his other books can be ordered directly from Rob here.