A few years ago, I wrote a piece for Hagerty that was something of a spring roll-out checklist—eleven things to check out before you jump into your winter-stored ride and head down the road with Born to be Wild blaring out of the ADS speakers.

Of course, if you know me, you probably suspect that for the most part, I’m not quite that systematic. The fuel-injected cars, due to their high-pressure electric fuel pumps and fuel return lines, are pretty remarkable in their ability to prime their fuel systems in a second and fire up with nothing more than a battery reconnect and a twist of the key. In contrast, the carbureted cars typically have dry float bowls, so it’s usually a race to see if the low-pressure mechanical fuel pump will suck gas into the bowl before the disconnected-but-sitting-for-five-months battery runs down.

I’ve had my ’73 3.0CSi, my 49,000-mile ’73 2002, Hampton, and my ’74 Lotus Europa Twin Cam Special at the house all winter. I recently agreed to do some work on a friend’s 2002 before we road-trip down to the Vintage (more on that next week), so I needed to reconfigure the space in the garage, which meant starting the sleepy cars.

This was the garage all winter. That’s the red E9 under the beige cover, and Hampton under the blue one. The e-scooter is my son Ethan’s.

True to form, with the battery reconnected and the key cracked, the E9 jumped right up, ready for dinner and dancing like the elegant lady she is and always will be.

If this juxtaposition doesn’t mark the coming of spring, I don’t know what does.

The Lotus had been sitting like her entitled little teenage-drama-queen self in the primo spot on my mid-rise lift all winter, waiting for a windshield replacement that was just finished last week, and a brake master-cylinder replacement that I still haven’t gotten to. It was time for her to surrender the throne. I charged the battery the night before, reconnected it, and cranked the starter, but the engine showed no signs of ingesting and igniting fuel. This was surprising, since the car’s original mechanical fuel pump has proven to be very stout; even after a winter sit, the car usually roars to life when choked. Plus, it’s a mid-engine car, so it doesn’t have the same have-to-crank-and-crank-to-pull-gas-from-the-tank-into-the-float-bowls problem that the carbureted front-engine cars have; the fuel pump and carbs are sitting about eighteen inches from the little twin gas tanks, and gravity alone probably gets the fuel about half that distance.

I quit cranking, extricated myself from the tiny little fiberglass tub, walked behind the car, and saw gas streaming onto the ground.

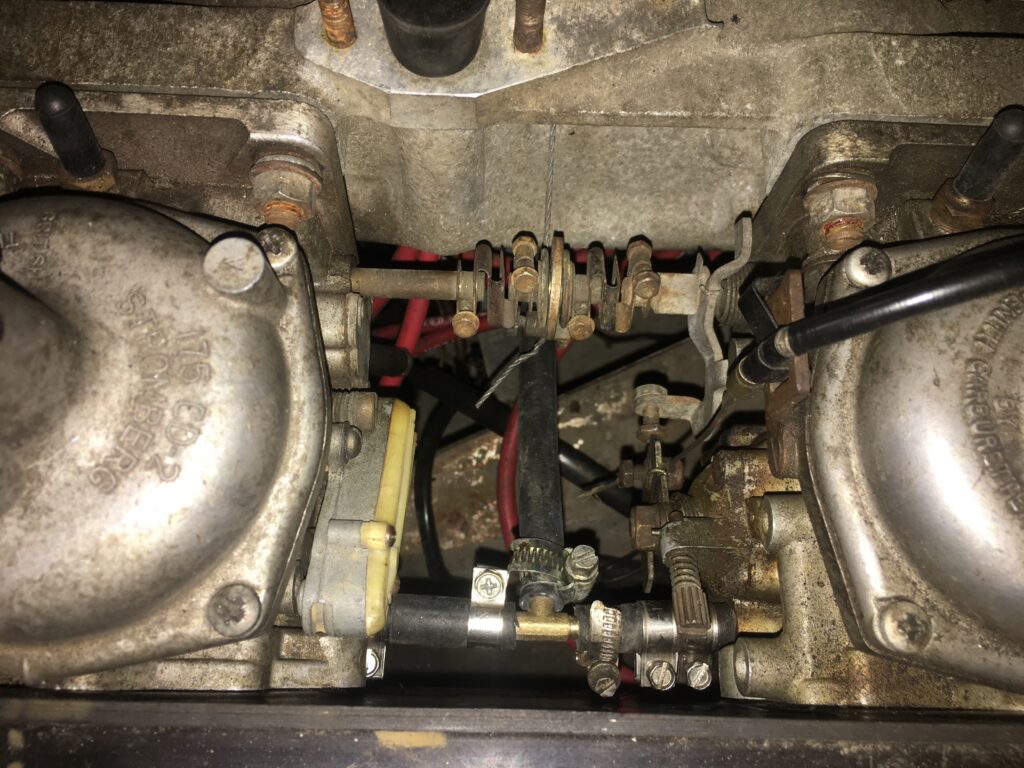

It turned out that the deluge was coming from two of the hoses on the tee fitting between the dual Strombergs. I’d used 10-11-mm “high pressure” hose clamps on all the fuel-line fittings, meaning instead of a worm drive that engages slots or ridges on the clamp, there’s a conventional screw that pulls together two tabs that stick up at a right angle to the clamp. Unfortunately, when I tightened the leaky clamps, the two tabs pulled together without staunching the leak. I believe that the problem was caused by my using a barbed tee fitting when I got the car running four years ago, and over time, the barbs bit into the inside of the hose, effectively loosening it and causing two of the clamps to run out of adjustment room.

This brass barbed tee fitting seemed to be the source of the leak. You can see where I replaced two of the high-pressure-style clamps with worm-drive clamps.

When I went to replace the leaky un-adjustable clamps, I realized that I could slide off the hose on the feeder line to the tee, but not the feeder hoses to the carbs. The fuel line running to each of the Strombergs is maybe an inch and a half long; there’s not enough length to be able to pull the hoses off. I must’ve installed these hoses when the carbs were off the car, slid the clamps on them, squeezed the carbs on either side of the tee fitting, installed the carbs on the manifold, and then tightened everything up. Fortunately, I was able to use a worm-drive-style clamp by unscrewing it all the way so it opened up, passing it around the hose, and tightening it.

Before I actually joy-ride the Lotus anywhere, I’ll give the fuel-delivery system a thorough inspection to see if anything else is amiss, but in this case I didn’t need to drive it anywhere, I just needed to de-throne the car from the lift and shuffle it to the back of the garage.

The next task was moving Hampton out of the space in the back of the garage. I had all sorts of plans for Hampton over the winter, but never got to them, so the car was as I’d left it last fall, which actually wasn’t a bad place. After all, I’d pulled out the EGR valve— which I suspected was the source of a vacuum leak that might’ve been the cause of lean running and which indeed broke in half on removal—re-jetted the carb, then took the car on a wonderful and long-deserved road trip to Vermont.

However, Hampton has had a long-standing problem with hard starting. Whenever I think I’ve fixed it, it does the Randy Quaid in Independence Day “Hello boys, I’m BACK!” thing. That, combined with the usual vagaries of a 50-year-old carbureted car that’s been sitting since November, meant that I wasn’t in the least surprised when the car ate up starter cranks like a teenager wolfing down pizza.

I popped off the air cleaner and looked down the carb throats while I worked the throttle. The accelerator pump wasn’t squirting—clear indication that the float bowl hadn’t filled up yet. I’ve sometimes resorted to temporarily splicing a little electric fuel pump inline to prime the system, but this time I elected for a couple of blasts of starting fluid. It worked perfectly; little Chamonix Hampton came to life.

But what’s that smell? Oh, crap.

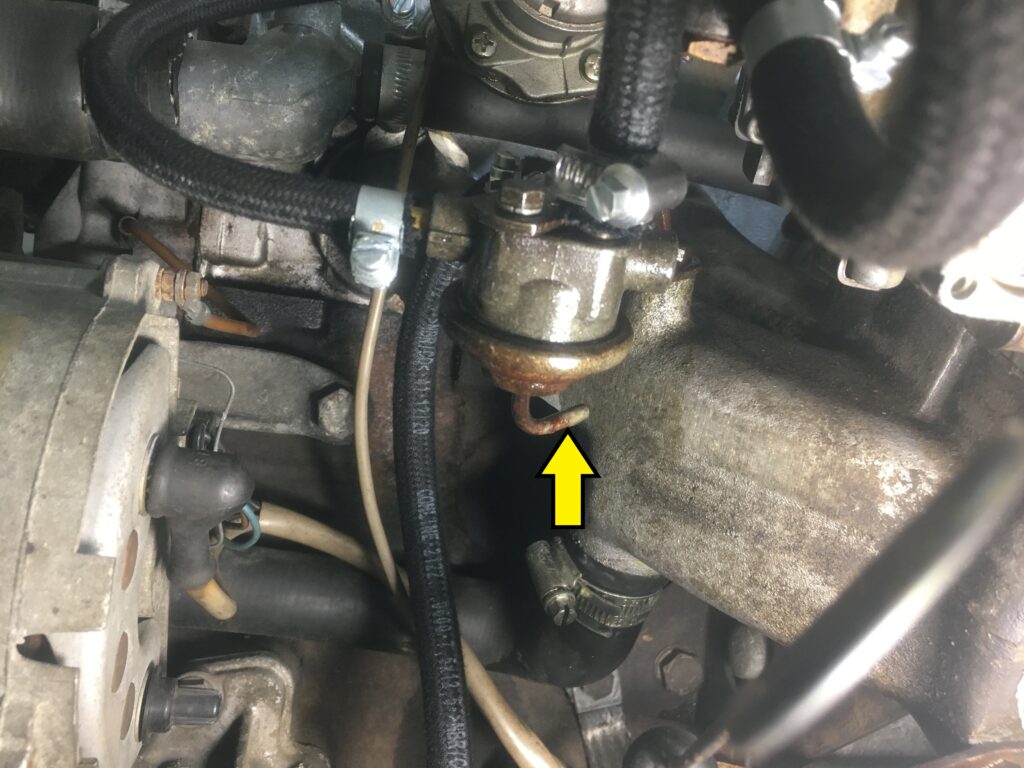

I looked and saw gas spurting out of the fuel return valve, also called the fuel recirculating valve. This was surprising for several reasons. Few 2002s still have their return valve, since its function of returning unneeded fuel to the tank is integrated with the original two-barrel Solex carb, and when the Solex is replaced with a Weber 32/36, as most of them have been, the valve is usually jettisoned. When I bought Hampton four years ago, it was a very original car, but it did have a Weber on it. I never really gave any thought to the incongruity of the Weber with the return valve present. When I removed the EGR valve last fall, I left the recirculation valve in place, but removed a few defunct vacuum lines.

The fuel was spurting from the port at the bottom of the valve, where a vacuum line had once been connected. Whether the line had been previously leaking but the fuel went into a plugged-up vacuum line, I’m uncertain.

The still-connected fuel return valve (center).

The vacuum port underneath the fuel return valve (arrow), where gas was unexpectedly streaming out.

This time I bypassed the return valve entirely, feeding the fuel pump output directly into the Weber. I still need to plug up the return line to keep fuel from spilling if the tank is full and the temperature rises, but with that, Hampton seemed quite happy to motor out of the garage and take his first spring drive.

At this point, I noticed that its inspection sticker was expired. A quick check revealed that everything was functional, so a trip to the local service station and $35 later, the car was legal again.

Not a bad day at Chez Hack.

I still need to launch the five cars in the rented warehouse space in Monson on the Massachusetts/Connecticut line into spring. I also need to choose one of them to drive to the Vintage in a month. Gee, if only I had some kind of checklist to keep me from getting into trouble…,—Rob Siegel

____________________________________

Rob’s newest book, The Best of The Hack Mechanic, is available here on Amazon, as are his seven other books. Signed copies can be ordered directly from Rob here.