Last week, using a Rube Goldberg-like contraption that involved my mid-rise lift, a scissors lift table, a transmission jack, a two-by-four-foot plywood board, four milk crates, and a ratchet strap, I pulled the transmission out of Zelda, my just-repurchased 1999 Z3 2.3i, in order to replace what I was virtually certain was a bad clutch-release bearing.

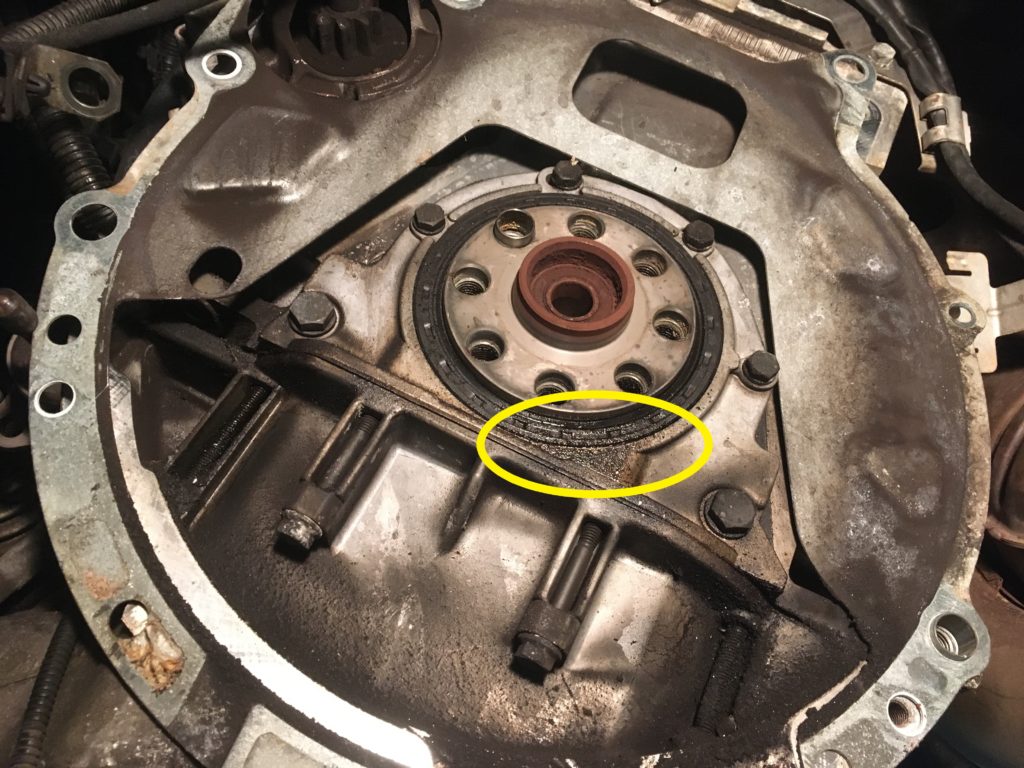

Part of my hesitancy in buying back Zelda was that the troika of the car’s generally ratty condition, the effort necessary to pull the gearbox, and the cost of the parts—particularly if I was wrong about the source of the noise—would push the car out of the worth-occupying-a-winter-garage-space zone for me. However, as soon as the gearbox was out and I looked inside the bell housing, I found that I was indeed correct in my assessment that it needed a clutch-release bearing. This hardly required anything approaching House-level genius diagnostic skills, as the bearing assembly was in three separate pieces:

Yeah, that’s bad.

So, with the transmission out and my fears that the noise might not be the release bearing and instead might be the dual-mass flywheel or the transmission-shaft input bearing vanquished, I quit for the night, secure in the knowledge that all I needed (at least on paper) was a clutch kit with a new plate, disc, release bearing, and pilot bearing. A quick online perusal showed that Luk was the OE supplier of the clutch, and that a Luk clutch kit was available for as low as $130 shipped. Reading deeper, however, I found some references to Luk’s release bearing having a lot of play; some said that the thing to do was order the proper BMW OE release bearing, or at least its OEM counterpart from Sachs. I found that Rockauto had one Sachs clutch kit in inventory for about $200 shipped. It didn’t come with a pilot bearing, but that was just another additional few bucks. I clicked and bought.

I’m unapologetic about my if-it-ain’t-broke-don’t-fix-it methodology, particularly on lightly-used cars, but I do try not to be an idiot, and few things would make me feel more idiotic than being wrong about some clutch-related part and needing to pull the transmission back out, so I inspected everything closely. And when I removed the release bearing and lever from the bell housing, I saw an alarming amount of wear on the sleeve that the bearing slides onto.

This doesn’t look good.

On closer inspection, though, I found that the ridges weren’t nearly as deep as they look in the photograph. Besides, most of the travel of the release bearing is on the part of the sleeve below these ridges (that is, the ridges were where the destroyed bearing was sitting and rattling around when the car was running and in gear). I entertained the idea of simply sanding the sleeve smooth, but I had a 44-year-old flashback to this part cracking in half on my Triumph GT6+. The sleeve appears to be a BMW-only part, but at about $48, replacing it wouldn’t deplete the taco budget, so onto the list it went.

Next was the release lever, also known as the clutch fork. I routinely reuse these, but the pattern of wear on this one appeared to be asymmetrical. Since it had been pushing a destroyed release bearing, I was concerned that because of the wear, it might not mate flush with a new one. Plus I had one of these break on the GT6 as well (of course, I had one of everything break on the GT6).

It’s a $30 part. I added it to the list, along with the $10 plastic pivot pin that it rides on.

The fact that the wear wasn’t symmetric troubled me.

When I’d disconnected the driveshaft during transmission removal, I’d inspected the giubo. I initially thought that it looked fine, and planned to re-use it, but now I gave it a closer look and noticed cracks forming around some of the bolt holes. I was surprised at how pricey giubos from anything resembling a reputable manufacturer have become. For $48 I ordered a Febi part.

The giubo was reusable in an emergency, but not worth it otherwise.

A couple of my Facebook friends chimed in on the issue of the dual-mass flywheel (DMF), which, let’s all just agree, is about the stupidest part ever designed for a car. I mean, what the hell? Let’s take a flywheel—a solid hunk of metal that normally lasts the lifetime of the car and is engaged by the starter motor at the ring gear on its circumference and spins the crankshaft and is pressed against by the friction surface of the clutch disc and the only thing that ever goes wrong with it is if it needs to be resurfaced due to excessive clutch wear—and turn it into a normal-wear-and-tear part that costs a thousand bucks from BMW ($400 from Luk). The rationale is that the dual-mass flywheel helps eliminate chatter and vibration, but the symptom of one going bad is—and you have to love the bizarro-world nature of this—CHATTER AND VIBRATION. Don’t get me started. Niagara Falls! Slowly I turned….

The meshing teeth of the inner and outer pieces of the dual-mass flywheel.

Having found the destroyed clutch-release bearing, there was zero question that it was the source of the chainsaw-like noise I’d been hearing, but that didn’t mean that the DMF might not also be bad. I read online that BMW’s recommendation is that the DMF can be re-used for one clutch replacement if its rotational play doesn’t exceed five teeth on the ring gear, and if there’s no discernible axial play. The rotational play was three teeth, and I didn’t feel any axial play at all, so I planned to reuse it.

I did, however, see a little bit of discoloration on the friction surface. I thought that this could indicate a little oil weeping out the rear main engine seal, but I didn’t see any oil at the bottom of the bell housing, so I was prepared to leave well enough alone.

Finally, there was the issue of the pilot bearing (the bearing in the end of the crankshaft that the tip of the transmission input shaft rides in). I stuck my pinkie in it and rotated it, and didn’t feel any roughness or play, but even I wouldn’t pull a transmission and replace a clutch without renewing the pilot bearing. To remove it, you either need a dedicated pilot-bearing puller or to try one of the methods of packing the recess behind it with something incompressible, like grease or soap or balled-up Wonder Bread or wet paper, and then putting a metal dowel through the middle and smacking it with a hammer. In doing the latter, you’re relying on the physics that the incompressibility of the packing material means that that when you smack the dowel with a hammer, that pressure has to go somewhere, and the somewhere hopefully is that it pops the entire bearing out of its recess.

For the record, I have never—ever—had this work. The pilot bearings in every one of my cars have been too tight. Once I tried it with grease, and all it did was shoot grease in my face. Another time it worked just well enough to pop the plastic cover off the bearing and have the grease extrude through it like a tube of toothpaste being stepped on. I’ve always relied on borrowing a bearing puller or renting one from AutoZone, but my local store no longer had one that fit the narrow bearing opening. So I ponied up and finally bought a proper OTC 1170 two-arm puller and slide hammer. Amazon charges $70, but they had one in an open box for $42, and I jumped on it. As cost-conscious as I am, and as infrequently as I need to pull pilot bearings, I do love knowing that I have tools like this in the toolbox. But even with the proper tool, I still had to smack the crap out of the slide hammer to get the bearing out.

The OTC 1170 pilot bearing puller completes the serious-car-guy tool inventory.

I’d hoped that with its long arms, the OTC puller could pull the pilot bearing out without my needing to remove the flywheel, but unfortunately that wasn’t the case; the bend in the arm hit the flywheel just before the notch reached the back of the bearing. My impact wrench zipped the flywheel bolts right out. I’ll just have to fabricate a bracket to hold the engine still while I torque the bolts back in (or find the bracket I made 38 years ago that’s lost somewhere in the depths of the garage).

With the flywheel removed, though, I could see a little wetness at the bottom of the engine’s rear main seal. The new clutch probably would be fine without replacing the seal, but together with the discoloration on the face of the flywheel, it felt silly not to address it. The seal and the paper gasket for the plate that hosts it are only about $25 for the pair, so one last order went in.

Just a hint of a leak. You’d change this, too, right?

Together with a few odds and ends like exhaust gaskets and nuts, the total outlay for the clutch-related parts was about $350.

I thought that I’d have all these parts by now, but with slow holiday shipping, exacerbated by a substantial snowstorm, not everything has arrived; I’m still waiting on the pilot bearing and the clutch fork. Of course, the beauty of a winter project, particularly on a roadster, is that there’s absolutely no rush. Still, maintaining that one-thing-per-night momentum is a good thing. Here’s hoping that the gods of winter shipping will deliver me the goods before I find some other must-have car that usurps Zelda’s garage space, or need to reconfigure the garage to make room to fix the snowblower.—Rob Siegel

Rob’s latest book, The Lotus Chronicles: One man’s sordid tale of passion and madness resurrecting a 40-year-dead Lotus Europa Twin Cam Special, is now available here on Amazon. Signed copies of this and his other books can be ordered directly from Rob here.