It’s 2020, and this means that later this year, my 1985 325e will be 35 years old—that is, if I still have it by its production date, July 3. If you know anything about me and BMWs, it should be that the E30 sparked my interest in the brand. A decade after riding in the back of my parent’s real estate agent’s E34 5 Series, by the time I needed a car of my own, one of the first I drove was an E30 325i convertible—in Calypsorot, if you’re curious.

I didn’t end up buying that Calypso convertible, but the seeds for what would what become one of the greatest obsessions of my life were sewn. Somehow, though, it would take another nine years years and a dozen other cars (most of them BMWs) before I would finally end up with an E30 of my own.

When I first found myself immersed in the E30 world, I didn’t know the difference between a 325i and a 325e. All of the 325i (and 325is) examples I found while browsing were newer, with what looked like sleeker, color-matched bumpers, and I naturally gravitated to these cars.

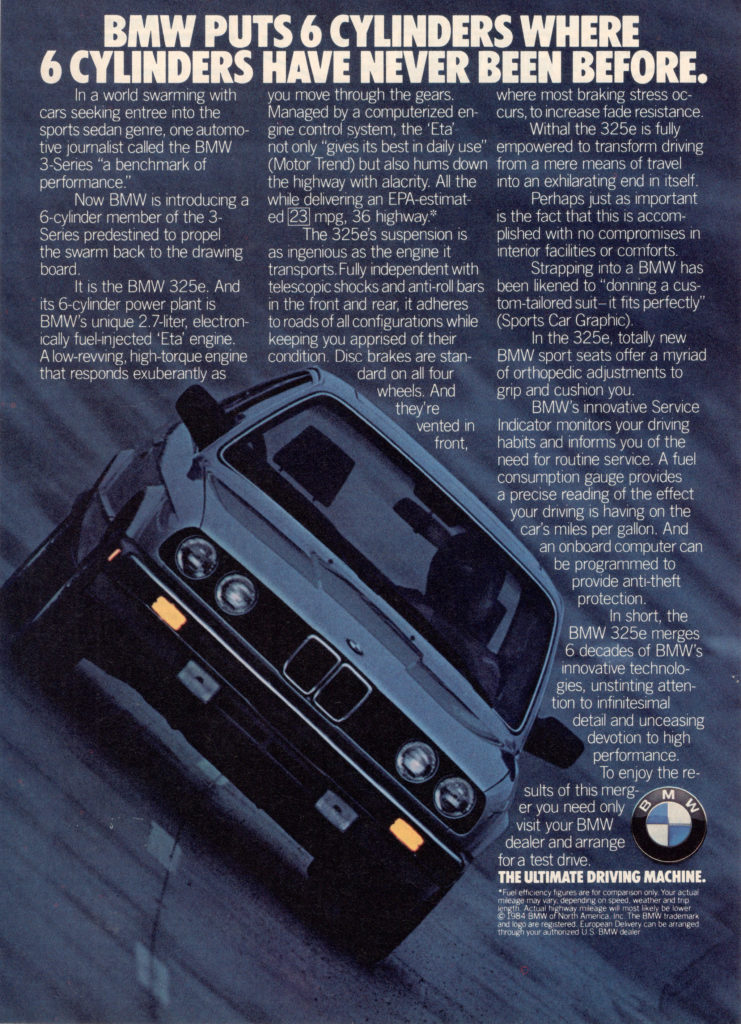

It wouldn’t take long for me to realize that the 325i superseded the 325e in the U.S., and that the latter was equipped with the more efficient but low-revving M20B27 eta engine. To indulge in a bit of a history lesson, the E30 325e was something of a stop-gap measure in the U.S. market. The E21 had been available with a six-cylinder engine in Europe, but the E30 325e was the first six-cylinder-powered 3 Series sold in the U.S.; the E21 it replaced had been available solely with a four-cylinder, first in two-liter displacement, and then with the 1.8-liter M10B18 engine. Although the M20 engine was in production, it would be a few years before that six could satisfy U.S. emissions standards—and BMW needed to make a statement with the new E30 3 Series.

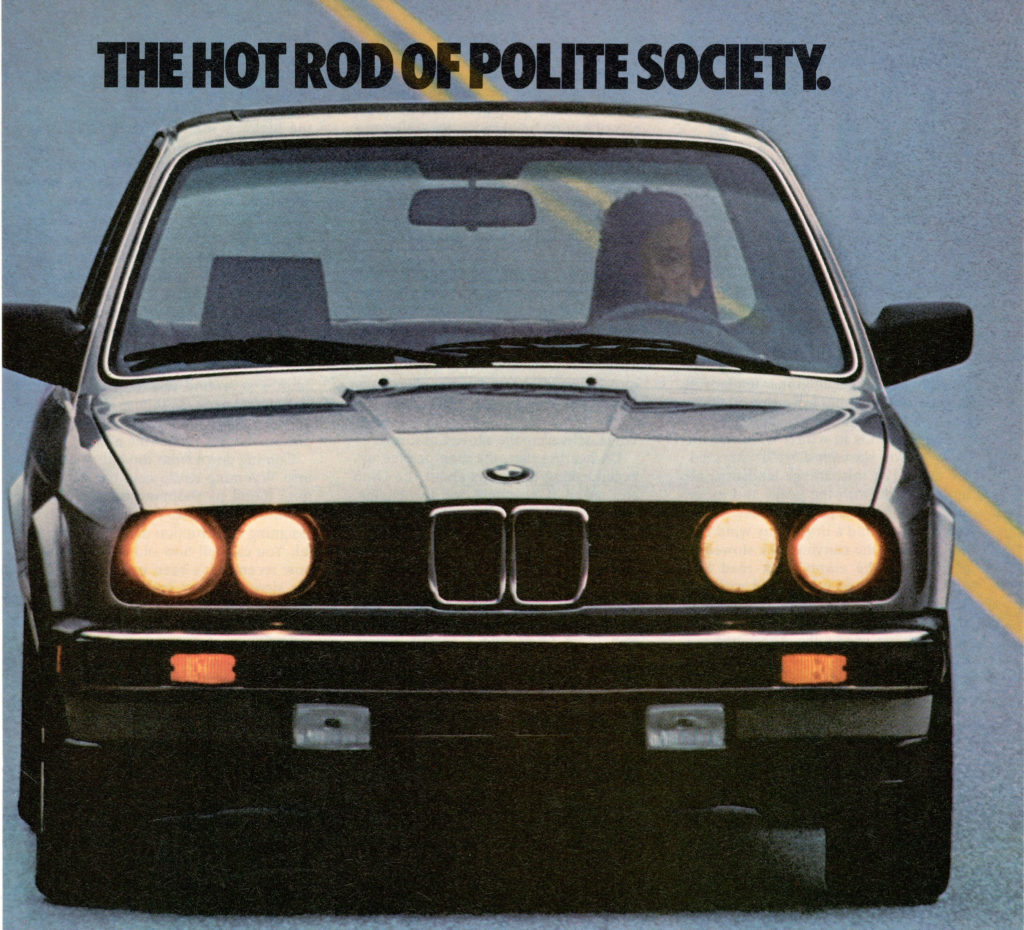

May 1982 marked the start of U.S.-market E30 production with the M10-powered 318i, long viewed as the underdog of the U.S. model range. Production of the U.S. 325e started in July 1983, after the 318i had already been around for a while, familiarizing the public with the E30 shape. Now the car carried a 318i badge, but retained the M10B18 engine, this time with updated Bosch L-Jetronic fuel injection, and period BMW marketing material shows that the arrival of a six in the 325e was obviously an event.

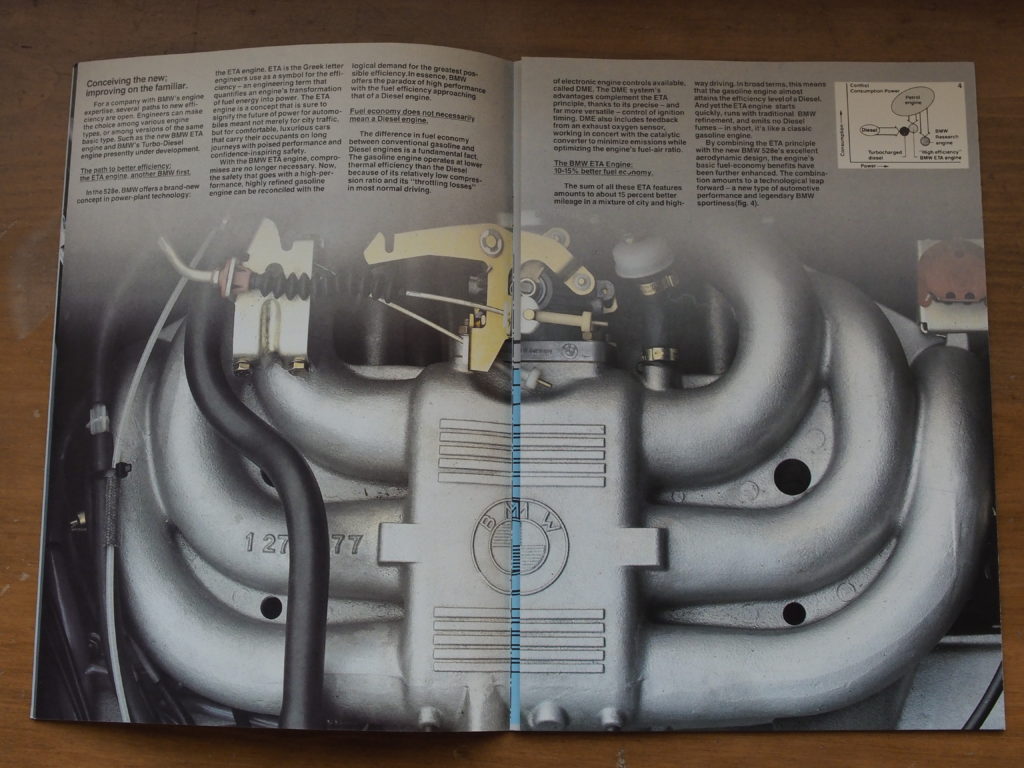

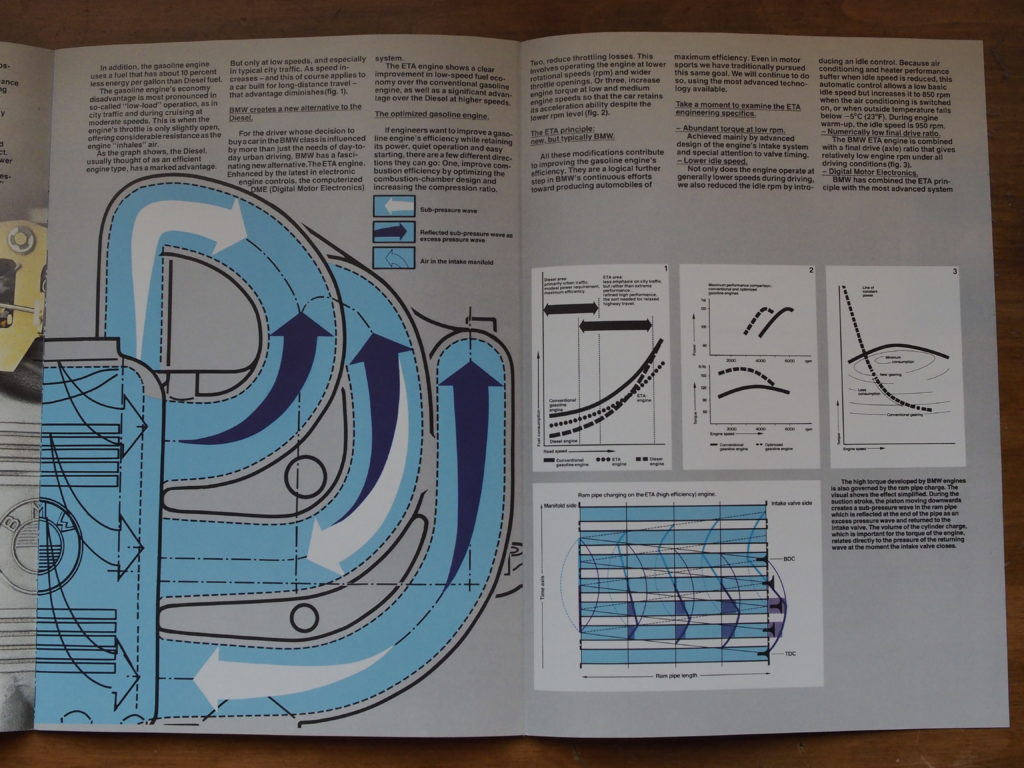

The M20B27, according to BMW brochures and other ephemera from when they were new, explains that the engine was designed with efficiency in mind. Although the redline arrived early, at just 4,800 rpm (or as low as 4,750, depending on your source), for non-super-eta engines, additional revs weren’t needed, as significant torque—170 pound-feet for U.S. cars (not much less than the S14B23 of the E30 M3)—arrived at 3,250 rpm. Never mind the fact that the regular M20B27 in the U.S., with 9.0:1 compression, made only 120 horsepower at 4,250 rpm; when shifting the slick five-speed at 4,000, that was all that you really needed in the 325e.

When it was time for me to dive back into the E30 market with some degree of seriousness, I was several years removed from my first drive in the Calypso convertible, and somehow I gravitated to models that it seemed no one else wanted. Big bumpers? Sign me up! I was searching for a project 318i; something about having an early E30 with one of BMW’s oldest and longest-produced engines drew me in. The E30 was one of the last BMW models sold with the M10, a special engine which had helped put the company on the map when two-liter versions were fitted beneath the hood of the 2002. Having approximately one-third the power of my N55-powered 135i also sounded like fun—we all know that there are few things more innately enjoyable in life than driving a slow car fast.

I was specifically searching for an E30 318i sedan with a blue cloth interior. Alpine White and Polaris Silver Metallic were my top two exterior-color choices, but I would take anything in one of the period gray or blue tones, such as Arctic, Basalt, Baltic, Cirrus, or Cosmos Blue, or Delphin Grey—and I wasn’t ruling out the more exotic colors like Bahama or Safari Beige. I had seen a handful of cars that met my criteria pop up for sale the years, all for incredibly reasonable prices, but when it came to buy, I spent months searching and found nothing worthy of consideration. Of course, I had been running concurrent searches for various other models I would consider—like the 325e—so as not to box myself into the market. But this wasn’t bearing much fruit, either.

Until I ran across my current E30.

That’s the 1985 BMW 325e five-speed coupe that I’ve owned for the last few years. Ranked just below my desire to have an M10-powered E30 was owning an eta. I am not sure what it is about the “e” on the end of the model designation proudly displayed on the trunk lid, which BMW re-used for their Efficient Dynamics campaign about a decade ago, but I always wanted one for its rather unique technical aspects. I wouldn’t have minded a 528e, either, but after owning two E28 535i sedans, I knew it was time to take the plunge on an E30.

I didn’t have to spend much to acquire my 325e, because it was a project when I bought it. The registration was expired, and I had feeling that if I took it in for a smog test, it would fail. It came with a laundry list of items I would spend the next few years addressing, like a mismatched hood, non-functional climate control, and an alternator with a failing rotor shaft bearing, among countless other little things we would never tolerate in a modern vehicle.

Both of these work in my 325e.

Within days of purchasing my 325e, I had an array of parts on order, including a new exhaust and catalytic converter, along with a number of other items necessary to make it roadworthy once again. I also had a fresh set of tires mounted, and the next few years saw everything from rust repair to the successful conversion and recharging of the A/C.

I’ve owned and bonded with a lot of different cars over the years, and the experience is always varied. With my 325e, it’s been fun all along; none of my work has seemed like a waste of time, even the projects that have taken a bit longer than originally planned. My time in the garage with the 325e has never become frustrating due to stuck bolts or broken plastic tabs, either, even though both of these have surely occurred. There’s just something rewarding about it, and when I tally things up, I feel that all of the sweat equity I’ve put into the car has been returned to me in spades, in the form of a fun, reliable, driving car that I always look forward to firing up. While it may not have been too far off from the junkyard when I purchased it, I’ve been able to transform it into a respectable daily driver, something I find immensely satisfying.

Of course, while my old 325e has working climate control—including cold A/C—a decent stereo, body panels that match in color, and a dependable driving record during my ownership tenure (knock on wood), I calculate that it has at least 300,000 miles, with character in the form of a cracked dash and beat leather on the driver’s seat, among countless other examples of its history. Although it’s a solid driver that I thoroughly enjoy, and it’s probably worth getting into for another enthusiast for a least a few more years, it would take a full nut-and-bolt restoration to really dial it in.

A BMW 325e was driven to victory at the 1986 IMSA Firestone Firehawk Endurance Championship at Watkins Glen by Ray Korman and Ron Christensen. The car helped to secure both the driver and manufacturer championships as well.

Even today, I could make the case for the 325e being my only vehicle. It’s got everything I need: seating for five (if you really, really need it), a trunk that swallows up a few sets of golf clubs, a nice big greenhouse that yields excellent visibility not found on any modern car, and all of the amenities I depend on when driving. Most everything works on my car, thanks to my efforts.

But driving the 325e is what I really love. Winding the M20B27 out through second and third is nothing short of serene (by the end of either gear I’m usually speeding on whatever road or freeway I happen to be on), and although the car sits on worn-out suspension with aging steering components, it’s still intoxicating to take through a properly cambered curve. It still makes enough torque to chirp the rear tires going into second at speed, which really keeps me interested in it: Extracting near full performance capability from the 2.7-liter long-stroke engine is a near daily occurrence when conditions permit.

So if the E30 325e is all I really need in a car, and if my specific high-mileage beater has treated me so well over the years, why am I considering selling it? The answer is simple: The 325e isn’t my only car, and although I’ve done well to divide my attention among my three-car fleet in terms of maintenance and washing, it’s the actual driving-and-use part of the triangle that has fallen short. While my E30 has seen more use than any of my other cars this year, that’s come at the neglect of my other cars, which have sat.

I grew up with big-bumper BMWs lining the sun-drenched streets of my neighborhood. There’s something about them that I will always desire.

But while some would see the decision to move on and save money in terms of insurance, fuel, and upkeep costs, enthusiast-car ownership almost never adheres to any known form of practicality, reason, or logic. I could easily sell my E30 and focus on my other two cars, both of which are semi-modern and ready to cross the continent at a moment’s notice, but I know that I will always miss the E30 if I let it go, and that I will yearn for another vintage BMW until I’ve got one leaking oil on the driveway.—Alex Tock

[Photos and scans via Alex Tock, BMW AG, Korman Autoworks.]