I want to like Formula E. I really do. Maybe it’s the high-pitched whirring that conjures up sound bites of the Jetson’s flying car for me, or the whisper-like silence on-track that makes me associate the cars with the subdued spirits of their F1 forefathers, but I just can’t seem to get into the high-tech street-racing series.

Just last week, while aimlessly browsing through suggested videos on Youtube, I encountered not one, but two videos comparing Formula 1 to Formula E, both of them unsurprisingly favoring the biggest open-wheel racing series in the world. As someone who was surrounded by ear-splitting machines growing up, like my grandfather’s Flowmaster-equipped ’40 Ford Deluxe Coupe-turned-hotrod, I always equated loudness with motorsport and cars in general. Later in my life, there was always something special about driving up to Auto Club Speedway during Bimmerfest and hearing the screeching exhausts of track-prepped BMWs from the parking lot—something I sorely missed when watching BMW in Formula E.

After reading and hearing the opinions of numerous enthusiasts on the matter, however, it seems as though the community still remains divided over the relatively new form that racing has assumed, even after nearly six years to learn to love it (or at least appreciate it). Maybe some of us, myself included, aren’t seeing Formula E for what it really is—progress.

Oh, what we’d give to hear the rumble of this 2000 Williams F1 FW22’s E41 V10 again.

Ok, hear me out—I wouldn’t be mad if a BMW-Williams FW26 V10 F1 car was the last thing I ever heard, but times are changing, and frankly I don’t understand why antagonism against Formula E still exists. As the years rolled on, we’ve shrunk our cylinders down from fire-breathing V12s to V6s, and almost everything in between. We’ve had powerplants both naturally-aspirated and with forced-induction, all of which had their own weaknesses at one point or another in history. Overcoming these challenges by recognizing faults is what drives innovation, and I commend Formula E for diving head-in. As they say, Rome wasn’t built in a day, and neither was an instantly-successful, radically-electric racing series.

The complete support BMW lineup for Formula E includes an X5 xDrive45e Rescue Car, i8 Coupé Safety Car, i3s Race Director Car, i8 Roadster Safety Car, and 530e Medical Car.

While the consensus seems to be that the RC-like nature of the electric engines is the main reason for disappointment in the series, it appears that some enthusiasts have other qualms about its existence, including the airfield and urban-based track layouts and locations, which seems to stifle the excitement of the sport—despite it being a street-based racing series in the first place. Some argue that the introductory driver animations are hokey, and that the power boosts labeled “Attack Mode” and enthusiast-generated “Fan Boost” created to promote overtaking and strategy among competitors, are gimmicky marketing, among other things. Others seem to be disillusioned with the overall race dynamic and that the series’ claim to be on the “cutting edge of technology” isn’t upheld by the performance of its cars, who currently have a max horsepower rating similar to that of a production-based, non-M 3 Series. What does the series really have to offer for BMW enthusiasts?

I had to find out.

Maximilian Günther behind the wheel of the BMW i Andretti Motorsports iFE.20 during the 2020 Berlin E-prix at Berlin Tempelhof Airport.

So I did. I watched a handful of races in the name of my own silly research study, and while I may not be hopping on the Formula E bandwagon anytime soon, I will admit that the sport has a certain charming appeal. Though controversial, I find that the tight racing and “bumper-car” style of driving exhibited by many drivers in the sport brings a sort of edge to the competition, especially when the mechanical likeness of all the cars is taken into consideration. The consistency between engineering allows there to be more competitive (and sometimes ruthless) driving between competitors, unlike in F1, where differences in chassis are becoming a shortcoming that is often debated and argued among fans.

I will remark that comparing F1 to FE may very well be comparing apples to oranges, however—though they are both based on the same platform, and are monetized in similar ways through marketing. That being said, the technology of both cars are widely different, and thus should be admired for those differences, not judged by them.

The i8 Roadster Formula E Safety Car is certainly on my list of best-looking BMW Safety Cars.

BMW, who has been involved in Formula E since the ABB FIA Championship series’ inception in September 2014, acts as the Official Vehicle Partner of the series and has been providing safety cars like the i8 Roadster and i3 for six seasons now. It wasn’t until the 2018–2019 season that BMW joined works outfit Andretti Racing to compete under the BMW i Andretti Motorsport name, with competitive racers Alexander Sims and Maximillian Günther behind the wheel.

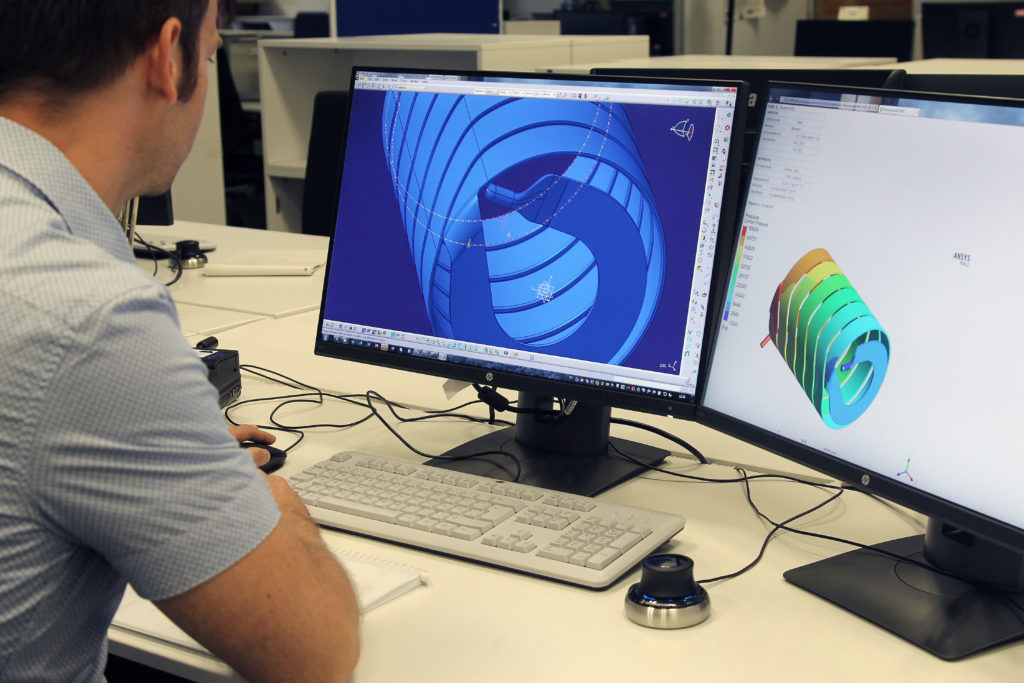

Entertainment factor aside, Formula E has proven to be a powerful tool for the German automaker in advancing their knowledge of electric technologies, something that has captivated me more than the racing itself. With the brand’s ever-evolving electrified image and upcoming iNEXT and electrified lineup debut, the decision puts BMW at the forefront of engineering. Motorsport has and always will be a proving ground for new technology, and BMW’s commitment to pioneering the electromobility of the future has already rewarded them with numerous technological insights, like the range limits of new battery cells running at peak performance.

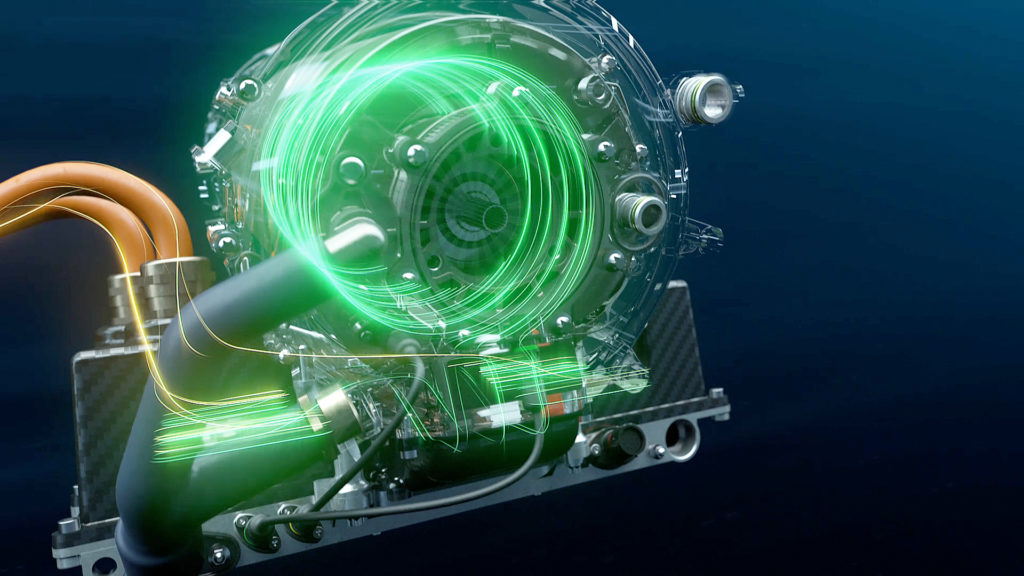

BMW’s eDrive01 electric drivetrain, found in the iFE.20’s predecessor, the iFE.18.

Though FIA regulations dictate that all vehicles are equipped with the same-spec battery, aero, and battery components, the teams are responsible for things like the powertrain itself which plays a crucial role in promoting on-track successes. The current, second generation (Gen2) BMW car, referred to as iFE.20, boasts a minimum weight of just under a ton at 1,984 pounds, and bears the title of the first racecar ever constructed from renewable textile fibers sourced from flax, which marks a move away from the carbon composites we are used to seeing. The single-seater road-going spaceship is good for a 2.8-second zero-to-60 time and 174 mile-per-hour top speed, courtesy of its max power setting of 335 horsepower. Compare that to the 369 horsepower 2020 plug-in hybrid i8, and you’ll learn to appreciate that “low” power figure a lot more.

Putting an emphasis on efficiency, the iFE.20 Gen2 car also has a 98.5% efficiency rating—a number that will influence the productivity and performance of BMW’s production electric vehicles for years to come. It is even rumored that the Gen3 cars, which could now be debuted later in the 2022/2023 season due to the global pandemic, will benefit from a lighter battery, lighter chassis, and an estimated max output of 804 ponies coming from regenerative braking, 469 of which will be used for normal racing. In theory, limiting the negative effects of the heavy battery handicap would allow the racecar to be lighter and therefore go faster, but it would require a larger power output to induce regenerative braking that would compensate for the energy loss during a standard 45-minute race.

This is exactly what I’ve come to admire most about Formula E—the challenge. The process of engineering and maturing technology like this in such a short time frame is what makes the series intriguing to me; interest owed less to the actual racing itself. I’ve found that I see the appeal to the series more when looking at it through the lens of an engineer, or in my case, an engineering student, as opposed to just another spectator. A change of perspective does wonders, and maybe you’ll see the sport in a different light if you focus on the technology and where it’s going. Racing is racing, and BMW’s current positions in both the 2020 driver and team championship standings are proof that the brand is making good progress in that respect.

I’m by no means saying to stop recording IMSA, DTM, and GT series on your T.V.—I know I certainly won’t. What I am saying, though, is to keep on eye on Formula E. One day, it may be the new norm, and rooting for a supersonic 900-horsepower single-seater BMW as it overtakes the competition may captivate you more than you ever thought possible.

The concept and idea behind the series is there, and in the coming years, the execution will be even better. The sport’s dynamism will allow it to adapt to the continuity of sustainability and environmental practices, allowing us to enjoy racing far into the future. The potential for greatness is there, and I have high hopes for the future of motorsport, and the production-based alternative-fuel technology it will pioneer. With more and more new manufacturers flocking to the series every year, it’s likely that BMW will face even more competition in the coming years, something that will surely enhance competition. Maybe it’s time I opened up my mind to the future of racing—with baby steps, of course. I won’t be forgetting the sound of an M54 bouncing off the rev-limiter anytime soon—and you can count on that.

Behind the scenes of BMW’s Formula E electric powerplant construction.

That being said—what are your thoughts on Formula E? What would you like to see the series implement in the future, and how would you like to see BMW i Motorsport evolve in the process?

[Photos courtesy BMW AG, LeMay Car Museum.]