American designer Chris Bangle joined Opel in 1981 after graduating from the Art Center College of Design in Pasadena. In 1985, he was poached by Fiat, where he designed the radical Fiat Coupe, the last car on which he drew every line.

Review by David Lightfoot

In 1992, Bangle was appointed chief of design at BMW. In the early Aughts, he led design efforts for all of the BMW Group brands, including BMW, Mini, Rolls-Royce, BMW M, Designworks USA, and BMW Motorrad.

Bangle left BMW in 2009 and moved to Clavesana, Italy, where he founded Chris Bangle Associates with his wife, Catherine. The New York Times called him “arguably the most influential auto designer of his generation.”

Throughout his career, Bangle carried a notebook with him at virtually all times, making notes and cartoon-like drawings in them. This book is filled with his comments and drawings, gleaned from decades of these notebooks.

The book is organized into 102 two-page chapters, almost all of which are 50 to 75 percent text and 25 to 50 percent cartoons/drawings used to illustrate his points. Available in hardcover in Italian (purchased from LibreriaInternazionaleHoepli for €23.75) or in English as an eBook ($25.99 from Amazon, or free with Kindle Unimited), this is a book unlike any car design book I’ve seen before, but I guess we should expect nothing less from Chris Bangle. I like the bite-size chapters, perfect for reading in bed.

Bangle was very controversial during his time at BMW, and the book shows him to be a very cerebral guy. He draws on a lot of history, art, architecture, economics, literature, and surely dozens of other fields. He made me think; sometimes I didn’t have the faintest idea of what he was really talking about, and many of his references went over my head—but most of the time I understood his points. This does not mean, however, that I always agreed with him. But I give him credit for always pushing the boundaries of car design.

One of my favorite chapters was about the GINA concept car. You may remember its fabric body over a movable framework, causing the car to mimic some of the movements of a human body, with the fabric acting much like skin. Bangle says that “GINA is Protestant but in a Catholic environment,” meaning that material properties are universal (Catholic), but their use cases are adapted to the individual need (Protestant, at least according to Methodists). It should be noted that Bangle did pre-seminary studies, intending to become a minister, prior to changing course and going to Pasadena.

While almost all the chapters cover just two pages, in several cases there are multiple chapters on a single topic—for example, the materials designers use has changed over the course of Bangle’s career. Thus, four chapters on Clay, Plaster, CAS (Computer Aided Styling), and virtual reality.

There are two series of chapters on how to view a car design. One series is about PSD (Proportion, Surface, Detail). At BMW, several designers developed an approach to viewing design proposals, including taping off a spot for the board members to view them; then the design staff would try to convince the board to use this approach, while the board members would do whatever they wanted.

Another series of chapter deals with “The Walkaround” used to evaluate a design. This deals with front, back, side, and plan views, plus viewing the design from varying distances and in different lighting conditions.

There are a couple of chapters that are completely unexpected. One includes the lyrics to a song that started with staff at Fiat, with subsequent stanzas from Bangle, all sung to the tune of “My Way.” Another off-the-wall chapter deals with insights from Bangles’s son, Derek, who spent a couple of summers working on the BMW Munich factory’s production line. At each station on the line, there are two teams; they do their task in 60 seconds and break for 60 seconds, while the other team does the same task on the next 3 Series, then does the same task again—all day long. Derek put doors on 3 Series cars.

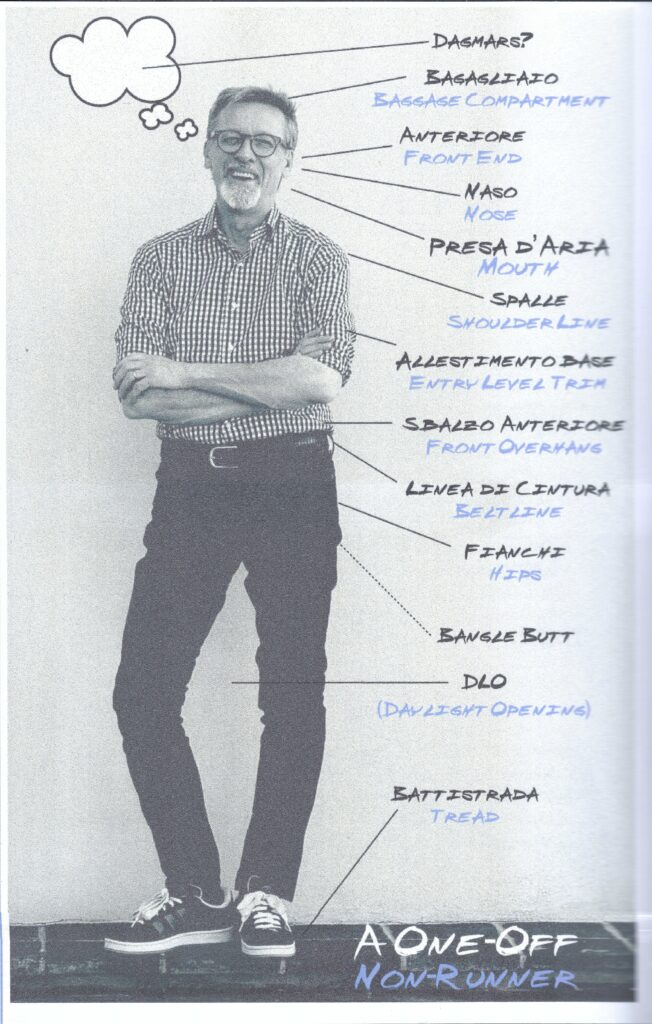

While the book is jam-packed with his small drawings, there is only one photo: an image of Bangle with a bunch of funny labels, including one pointing to the real Bangle Butt.

While there are no photos of cars in the book, there are plenty of insights into Bangle’s work at BMW, including some of the controversies and the politics of getting designs approved by a company dominated by engineers. In the end, he comes off as a savvy guy who left BMW too soon; he should have stayed longer and been more recognized for his successes.

Bangle also comes off as a person who would probably be fun to hang out with. I’d love to hear one of his cartoon-punctuated lectures on design. I recommend the book highly. It is a very pleasant, thought-provoking read. You’ll appreciate the work of car designers in general more, and the effect Bangle had on BMW and car design specifically.