[Note: I’ve been asked not to include shoot title or location or photos of the set, actors, or crew. Apologies if the photos don’t live up to the title.]

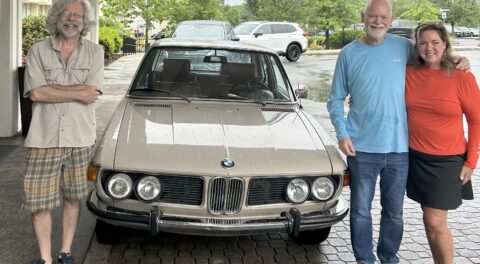

In late April, I received an email from a writer/filmmaker who read a piece I wrote about the Bavaria and wanted to know if I’d rent the car for use in a short film. I jumped on Google, and quickly learned that she was legit. We swapped a few emails and then a phone call, during which she told me the basics of the shoot. We clicked at the human-to-human and the writer-to-writer levels, and by the end of the conversation, I verbally agreed to rent her the car. She said that filming would likely occur in New York’s Hudson Valley in early June, and that she’d refer me to her producer to work out the details.

Now, I’ve loaned 2002s to folks for weddings on verbal agreements, but a film shoot is a commercial venture, so some kind of formal agreement was appropriate. The producer said that the film shoot had prop insurance, but I wanted to be certain that I was covered on my end. I spoke with Hagerty, who insures the Bavaria and all my other vintage cars, and found out what the hoops were to jump through to get a commercial rider. It was a nominal annual charge plus the film location, dates, and license information on anyone driving the car. Easy stuff.

I then did a little research on what would be an appropriate rental fee. I learned that cars used as extras in street shots fetch maybe one or two hundred bucks a day, but expensive or rare cars that are highly visible and used almost like characters in the film can command thousands. $500 per day for the Bavaria seemed reasonable to me.

But I also read posts on sites like GarageJournal that said, basically, don’t. They warned that no matter what you might have in writing about how the car is used and what they can and cannot do to it, no one is going to be as careful with your car as you are. When it is in the hands of a film crew, they are likely to do whatever they think they need to in order to get the shot, and this can result in damage. At a minimum, the posts said, you’re wise to insist that you need to be onsite at every moment.

Transportation was also an issue. The filmmaker and the producer had offered to pay to ship the car, but the logistics were challenging, because the car was in storage in the warehouse I rent in Monson on the Massachusetts-Connecticut line, which meant that I’d need to go there to pull it out and meet a shipper.

I began planning to instead bring the car home where a shipper could grab it. But the more I thought about it, the more I realized that this wouldn’t work, either, since arranging shipping isn’t like making a dentist appointment; pick-up times are approximate and are often delayed by days. Really, the only way to guarantee that the car would be there at a specific day and time was to drive or tow it there myself.

Film-shoot dates in early June and the location in the Hudson Valley were confirmed. The producer and I talked about cost. I obtained a commercial estimate for open-transport shipping of $450 each way. I figured that for me to play the part of the shipper, I’d be renting a U-Haul trailer, hooking it to my truck, hauling the Bavaria out there, returning empty, and reversing the process to pick the car up, so I multiplied the $450 estimate by four. I wrote up a simple memorandum of understanding listing the rental, shipping, and insurance-rider costs, as well as some other common-sense things like prohibiting the use of adhesives to affix cameras and requiring that they pay any additional expenses including damage below my deductible.

The first surprise was that my cost proposal went tilt. The producer called me, saying that they simply didn’t have that much in their budget.

The second surprise was when he said, “There’s a guy out here with an old Mercedes he’ll rent us for $500 for the day.” I was an engineer for 35 years, and I’m still used to thinking of things in terms of requirements. I asked, “Is a Bavaria required for the film or isn’t it?”

“Well, the author certainly wants it,” he said.

He said that they could rearrange the shooting so that they’d only need the car for one day, and asked if that would simplify the logistics and allow me to drive it out and back for $750, and added that they’d put me up if the shoot ran late enough that I didn’t want to drive back after dark. I thought about it and said that yeah, I could do that, but if it ran into a second day I’d have to be compensated, and I couldn’t drive out thinking that it was for one day but wind up staying three. He verbally agreed.

Then the third surprise: “Is this car a standard or an automatic?”

“Standard.”

“We’re not sure if the actress can drive a stick. Do you have another one that’s an automatic?”

I wasn’t sure whether to laugh or scream. “The only automatics I have are the truck and the RV.”

But because I liked the author and was intrigued by her asking so specifically for a Bavaria, I agreed—subject, of course, to their verifying that the actress could, in fact, row gears.

So we both signed the memorandum of understanding that set everything in motion. I triggered the commercial rider with Hagerty (a big $50 plus-up to my annual bill, passed on as an expense), and arranged access with the owner of the Monson warehouse. Initially he said that he could meet me there early Monday morning, but he wound up having to go on the road. Fortunately. he was willing to give me the combinations to the gate and the building.

I agreed to be at the photo-shoot location in the Hudson Valley by 9:00 a.m., so I loaded the trunk of the E39 with Bavaria spare parts as well as things like jumper cables and starting fluid—I hadn’t driven the Bavaria in months—left Newton before 5:00 a.m., and headed for Monson.

It was a little spooky being in the 275,000-square-foot warehouse all by myself with the lights out (the owner said that turning them on would be difficult to explain, offering. “Honestly, if you think you’ll be in and out of there quickly, it’d just be easier to use a flashlight”). I have one of those flashlight headlamps, so I strapped it on, uncovered the Bavaria, reconnected its battery, and with about twenty seconds of periodic cranking, the float bowls of the Weber 32/36s filled up and the car settled into a lumpy idle, which smoothed out as it warmed up. I locked the warehouse and headed for the highway.

The Bavaria heads for the Hudson Valley.

Unfortunately, as soon as I was under way, I caught a whiff of the unmistakable sweet smell of antifreeze. Damn! I stopped and checked the car thoroughly, but didn’t find any dripping or wetness, but I could see through the translucent overflow tank that the coolant level was a bit low. I pulled into the first open convenience store and bought a gallon of pre-mixed coolant.

Fortunately, over time, the smell dissipated. I watched the temperature like a hawk and stopped several times to verify that the level in the overflow tank wasn’t dropping, but whatever was causing the problem didn’t become acute. I relaxed enough to enjoy the drive out the Mass Pike, over the Berkshires, and down the always-beautiful Taconic Parkway.

I arrived at the shoot location and met the author and the crew. They loved the car. A lot of time was spent trying to get a shot where the cover was pulled off the car in a very photogenic way. First they tried it like a magic trick, then like a sideways version of a nightgown sensuously dropping over shoulders, but it kept snagging on the edges of the drip gutters. I used electrical tape to make little ramps so the gutters wouldn’t catch the cover. This actually worked, but then the cover snagged on the antenna, the wipers, and the mirror. It was a little lesson in the tradeoff between getting the shot you want versus keeping on schedule.

The car waits to be uncovered.

It was then time for the actress to drive the car. The filmmaker told me that unfortunately, she’d learned that the actress’ manual-transmission skills were rudimentary at best.

I decided to see for myself. “Tell me about your manual transmission experience,” I said.

“I have driven a stick before,” she said, “but I don’t do it often.”

“When was the last time you did it?” I asked.

“Yesterday.”

Out of decorum, I did not ask if “yesterday” was the only time she’d ever driven a stick.

“I won’t burn out your clutch,” she said.

I thought about it. “Good answer!” I replied.

There was a twenty-minute window before filming was scheduled to start, so I took her out for a short lesson on the gravel driveway where most of the filming would occur. She did okay, not unlike my kids when they were learning. Her main problem was releasing the clutch too quickly, which is way better than feeding too much gas. The gravel driveway was fairly forgiving; when she let off the clutch too fast, the rear wheels just kicked up stones. I showed her the trick of using the handbrake to get started on a hill, but this is something that takes a lot of practice.

I was keenly aware that I was in an awkward position, since saying no would’ve ground things to a halt. At some point, you make a gut-level decision about these things. The Bavaria is not a high-dollar car. It’s not precious to me in the way my E9 is. The actress’s clutch skills were passable. The car’s transmission and clutch are pretty stout. Nearly the entire shoot was going to be on gravel. I could fault the producer for not having checked the actress’s experience, or having bent the truth if he had, but here we were.

I winced occasionally, but she did okay. If anything, the film crew thought that the little gravel chirps looked cool.

One of the driving shots was slated to use a “hostess tray”—a large apparatus that hangs on the passenger door and holds a film camera aimed at the driver. I inspected the hardware and noted that it used four round discs, each about two inches in diameter, to brace the tray against the door skin. It looked like each needed a rubber pad much larger than the ones that were on them. The cameraman admitted that they’d normally use big, thick rubber squares, but they didn’t have any. “We’ll mount the whole thing on a furniture blanket, then put towels under each of the discs,” he said.

“I need to judge it for myself,” I explained. I put the furniture blanket on the door sill, began to lift the hostess tray onto it, estimated that it weighed at least 35 pounds, put it back down, and simply said no. They strapped the hostess tray onto a rental car instead and got the shot by driving alongside the Bavaria.

Strapping this to the Bavaria was a hard no. It went on a rental car instead.

Nearly everyone on the crew treated the Bavaria with a lot of care. The glaring exception was a young crew member who put both her clipboard and clapperboard (the thing where you go “Scene 4, action!” and slap it closed) on the trunk lid. The filmmaker immediately corrected her. She nodded distractedly, but didn’t remove the items.

I walked up to her and gently said, “You can’t lay anything, especially hard objects, on the paint of a car like this.” She removed them but made no apology. I let it go. The filmmaker witnessed this, walked over with concern, looked at the trunk lid, pointed to a long, faint superficial scratch, and asked, “Was that already there?”

I said, “I’m pretty sure, yes.” And I was.

It all worked out—well, almost all. In terms of broken bits, the only thing that went wrong was that after the shoot of the final scene, the author and actress reported that something had broken on the rear door. I inspected it and found that the plastic piece connecting the armrest to the door had cracked. They were livid and apologetic, and offered to pay for it. I didn’t have a cow over it—it’s a 50-year-old piece of plastic on a rear door that probably hadn’t been pulled closed from the inside for 40 of those 50 years. When I arrived home, I searched online for the piece, found that it’s only available in black (part number 51411815236), but that Coupe King sells a little bracket that sits inside it and reinforces it. I added the $65 cost for a pair of brackets to the car-rental invoice. I’ll glue the piece back together, mount it with the bracket, and never look at it or think about it again.

Whatever.

It was after dark when the shooting ended, and I had no desire to drive the almost four hours it would take to get to the warehouse, swap cars, and drive back home, so I took them up on their offer for a room for the night. In the morning I drove east—the Bavaria’s clutch apparently no worse for the wear—retrieved my E39 from the warehouse, and headed home.

To me, the main thrust of this whole endeavor was saying yes to a person who wanted to use the Bavaria for something cool. I try to be someone who says yes. And the logistics and the modest risks notwithstanding, it wasn’t difficult to say yes, despite some things that weren’t entirely clear at the outset and a few surprises on the set.

Really, sometimes you can make things as simple or as complicated as you want. I take a certain amount of pride in probably being the only person on the planet who could’ve provided her what she asked for and who didn’t bail out or blow a gasket over what were, in the big scheme of things, fairly minor issues.

However, the fact that you’re likely reading this and going, “Are you freaking nuts? I would never let someone do that to my car!” means that if someone asks to rent your car for a movie shoot, you should say no. And that’s okay. But if you do choose to do something like this, and have your car insured with Hagerty, know that there’s a very straightforward mechanism within your policy to cover the car. Other insurers probably do as well, but be sure to call and ask.

And yes, if it’s a car that you care about, I agree with the advice I read that you should absolutely require to be on the set at all times to monitor, and if necessary, veto what they’re doing with your car. I was originally prepared to drop the Bavaria off for a three-day shoot. Seeing what happened when I was on the set, I now realize how risky that would’ve been.

And yes, next time I’d make sure that the actor or actress really knows how to drive a stick. Knowing what I know now, would I rent out my E9? That’s easy. Are you freaking nuts?—Rob Siegel

Rob’s new book, The Best of The Hack Mechanic, is available here on Amazon, as are his seven other books. Signed copies can be ordered directly from Rob here.