The year was 2012. The place was the parking lot of the Hawthorne Inn in Winston-Salem, North Carolina, the host hotel for what was still called Vintage at the Vineyard. The head gasket in Paul Wegweiser’s 1972 2002tii (aka the F-Bomb) had blown on the way back from dinner.

Wegweiser and fellow mechanic extraordinaire Ben Thongsai replaced it in the parking lot of the hotel in an hour and 56 minutes.

That lightning-fast time was amazing, but just as remarkable was the fact that they began disassembly before they even had a replacement head gasket in their possession (one miraculously was crowd-sourced). With the repair in the hands of these two gifted professionals, your Hack Mechanic was a third wheel, relegated to holding the flashlight and twisting paper towels into makeshift Q-Tips for Paul to clean the oil out of the head bolt holes in the block.

The crowd erupted in cheers when Wegweiser restarted the car. It was a remarkable event, half repair and half performance art, and remains the benchmark for on-the-road vintage-BMW repairs.

The stuff of legend.

None of that will happen with Louie.

As I wrote about here, my main winter BMW-related project is going to involve some R&R on the head of Louie, the ’72 tii that I bought five years ago and did the whole Ran When Parked adventure with. The head gasket isn’t blown and the car currently runs fine, but I have three reasons for preemptively decapitating it:

First, when I bought the decade-dead car in early winter 2017 and resurrected it during the week-long adventure in Jake Metz’s pole barn in Louisville, there was a difficult-to-seal oil leak from the valve cover. It took me a while to see that the head actually was cracked—not through a combustion chamber, but through a boss at the left rear corner into which a valve cover stud threads. This was why the valve cover wouldn’t seal: Tightening the nut on the stud just made the crack yawn open wider.

Someone had tried filling the crack with blue RTV, so clearly a previous owner must’ve been aware of the issue, and it’s reasonable to assume that the cracked head and an accompanying estimate to deal with it may have been the reason why the car was parked. I did several long road trips in the car, but the crack caught up with me on the way home from the “Icon” exhibit at the Foundation. It worked its way through to the outside of the head, and oil began dripping onto the exhaust manifold. A field repair with J-B KwikWeld held it together, and I’ve continued to drive the car—but really, the head needs to be removed and brought to a professional to ascertain whether it can be properly repaired or needs to be replaced.

The smoking crack.

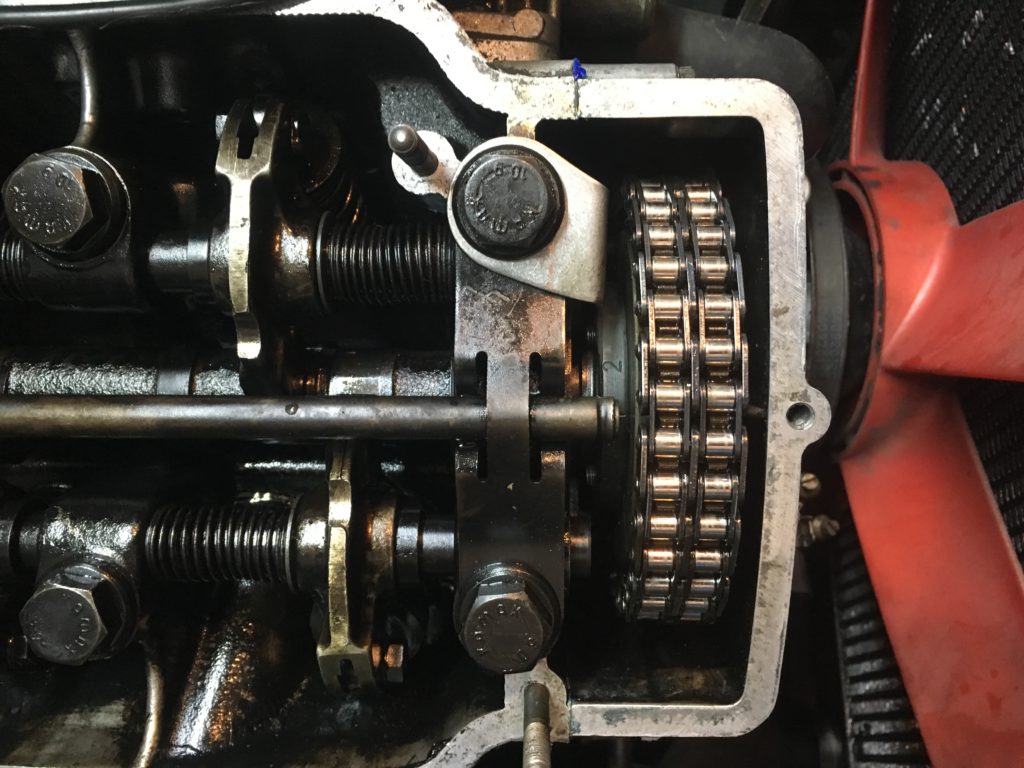

Prior to the “Icon” trip, I discovered that the plug in the end of the intake rocker shaft had worked its way out and was threatening to swan-dive into the timing chain. I addressed the issue by installing a special angled bracket held on by one of the head bolts, but it really should be fixed properly by replacing the rocker shaft.

Effective, but less than optimal.

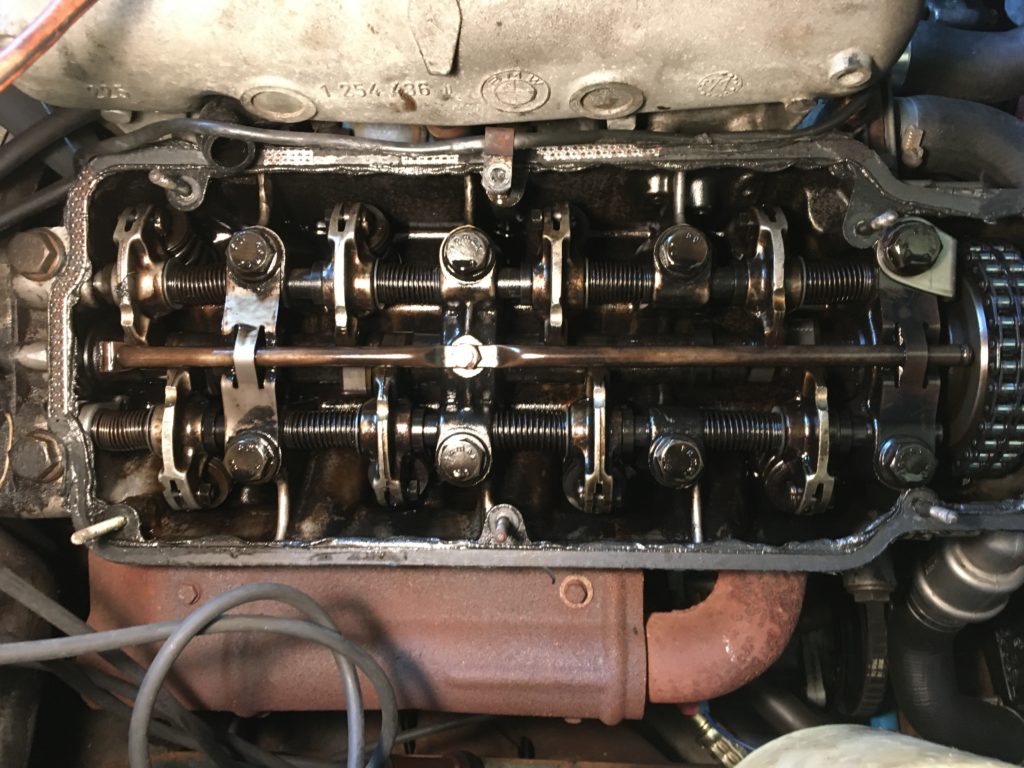

Second, while, incredibly, the car runs fine, exhibits absolutely no trailing-throttle smoke (the textbook sign of leaky valve-stem seals), and shows no coolant in the oil, the high level of black varnish indicates that this head has never been off this engine. As Wegweiser’s parking-lot adventure with the F-Bomb (and similar recent head-gasket failure in a different 2002) show, head gaskets on vintage cars do fail, especially if the car is wailed on regularly.

On some heads, when you pull off the valve cover you’re greeted by something shiny and clean, indicating recent work. This is not one of them.

One of the joys of a vintage car like a 2002 is that the lack of electronics and emission controls makes head-removal straightforward: Set the engine to top dead center, pull out the distributor, undo the nuts holding the exhaust-manifold studs to the downpipe, pull the front coolant hoses, remove the upper timing cover and gear, undo any electrical connectors and fuel, air, and coolant hoses from the intake manifold, remove the head bolts, and lift the head with the intake and exhaust manifolds still attached. That’s pretty much it.

Of course, on a 50-year-old car that’s never had its head off, any of those things can drag you to a halt. Sometimes it’s the nuts on the downpipe; the corners can round, or they can have a death grip on the studs to the point where they snap. I’ve had this happen often enough that I soak the nuts in SiliKroil, then heat them with a MAPP-gas torch and apply a little beeswax before hitting them with the impact wrench.

This time their removal was trouble-free.

A likely source of delay—but not today.

Despite Wegweiser’s and Thongsai’s one-hour-and-56-minute decapitation and re-capitation of the F-Bomb, pulling the head off a tii is a bit more challenging than doing it on a carbureted 2002, since you need to deal with the injection system. The thin plastic injection lines have to be unscrewed from the injectors, and to reach them, the intake manifold’s plenums need to be removed. Plus, most ’72s like mine have the plastic intake plenums. These proved to be so crack- and leak-prone that BMW quickly superseded them with metal plenums. The plastic plenums snap-fit onto rubber O-rings on the manifold. They don’t come off easily, and a cold garage in winter isn’t exactly the environment to make the plastic pliable. I had the heebie-jeebies rocking them side-to-side to pull them off, but I think that I managed to do so without cracking them.

Plastic intake plenums off. So far, so good.

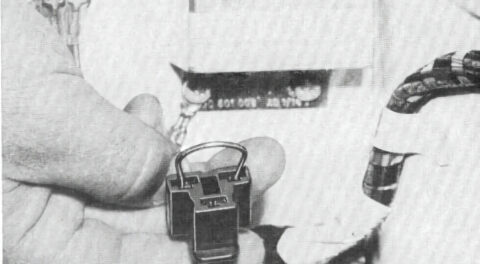

The main problem I had was with the connection of the throttle body to the linkage. There’s a pinch collar that attaches the shaft that comes down from the “tuna can” on the throttle body to the rod that comes up from the bottom and pulls the linkage elements that move the arm on the Kugelfischer injection pump. Inside the tuna can, the shaft is permanently attached to the underside of a half-moon-shaped cam that, in turn, opens the throttle plate. To pull the head off, you need to loosen the bolts on the pinch collar, unbolt the throttle body from the intake manifold, and draw the upper shaft out of the collar.

The pinch collar connects the linkage rod to the shaft coming down from the tuna can.

Decades ago, the first time I pulled a tii head, the upper shaft was stuck in the pinch collar. I wasn’t sufficiently gentle in the application of torque, and snapped the half-moon cam clean off the top. Not surprisingly, I’m now hyper-aware of this whenever I need to pull a throttle body off a tii.

The attachment of the shaft to the cam inside the tuna can.

I found that I couldn’t separate Louie’s upper shaft from the pinch collar, and I didn’t want to force it, so instead I just swung the throttle body, still attached to the linkage, over to the left and out of the way. It’s visible at the top of the photo below. You can also see what looks like a shredded valve-cover gasket, but instead this is the remnants of Permatex “The Right Stuff” sealant that I used to get the thing to stop leaking when I couldn’t tighten the valve-cover gasket down due to the crack in the boss with the stud.

Close to lift-off.

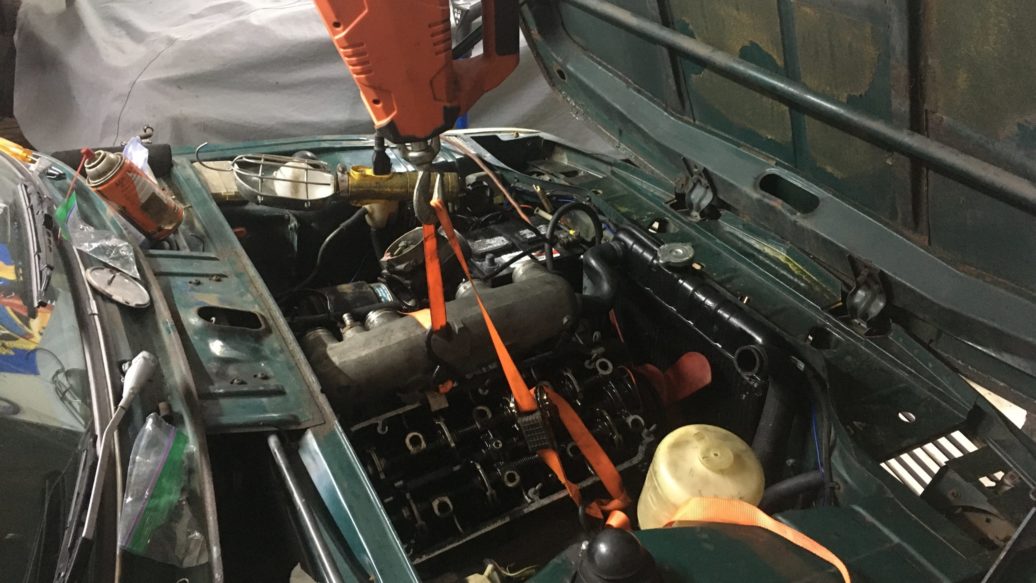

It’s pretty easy to lift a bare head off a 2002 block, but if the manifolds are still attached, it’s more than my 63-year-old back can deal with, so these days I employ my little Warn PullzAll electric winch. I have a hook sunk into a cross-piece which in turn is lag-bolted to two joists in the ceiling. The fully-assembled head with the manifolds on it probably weights about 40 pounds; it’s not like I’m lifting an engine. I’ve used the arrangement many times. The video can be seen here.

Of course, it’s long been said that any sort of a hoist or winch is a device to test the tensile strength of whatever you’ve forgotten to unhook, and I had in fact forgotten one thing: the heater hose on the back of the head. This is especially ironic, since I earlier advised, “Pull the front coolant hoses.” Fortunately, my oversight didn’t cause any damage.

And… off.

So: Louie is decapitated. It took longer than half of Wegweiser’s and Thongsai’s one-hour-and-56-minute job, and doing the necessary rejuvenation on the head and then reattaching it will take considerably longer than the other half of 1:56. It’s not the stuff of legend. But it’s what needs to happen.

When it’s done, though, you do have my permission to erupt in cheers.—Rob Siegel

Rob’s new book, The Best of The Hack Mechanic, is available here on Amazon, as are his seven other books. Signed copies can be ordered directly from Rob here.