It’s been a weird few weeks here at the House of Hack. There was the no-sale of my survivor 2002 “Hampton” on Bring a Trailer, followed by l’affaire Magnus Walker, which required me to execute the overdue step of bringing my M coupe and 3.0CSi back from their extended over-winter stay in my friend Mike’s big garage. These events swelled the number of cars in my driveway to a level where there’s not a lot of open asphalt left. I still haven’t heard from the new owner of the house in Fitchburg where I rent four garage spaces regarding whether she’ll leave our arrangement as is, raise my rent, or kick me out. So, as I wrote here, I feel like I’m waiting for a bomb to go off.

What’s a stressed-out guy to do? Drive.

First there was the Nor’East 02er spring gathering and drive. Things began with a hang-out at the Stevens Estate in Andover, Massachusetts, followed by an easy drive up to Woodman’s in Essex, a restaurant famed for their north-shore fried whole-belly clams. I ordered the platter, which, together with the fries and onion rings, was so heaping that it resembled a cake. It nearly put me into what my wife and I refer to clinically as a clam coma, something that must be experienced once a year. Maybe twice. But definitely not more frequently. I wanted to photograph it and send the picture to my doctor and ask, “Is this what I’m not supposed to be eating?” but I’m not sure that he would’ve thought it was as funny as I did.

Since the skies were clear, I stretched Nor’East 02er decorum and drove the E9 3.0CSi instead of one of the 02s. By sheer coincidence, my friend Andrew Wilson did the same. We parked both E9s at the very end of the parking lot, away from what we jokingly referred to as the unwashed 2002 rabble (seriously, we were just trying not to interrupt the photo). One of the event organizers, Peter Rodriques, thanked us for bringing “the ladies.”

The kick-off at the Stevens Estate in Andover: That’s Nor’East 02er organizer Peter Rodriques’ lovely ’76 Inka in the foreground.

The sweep of 02s at Woodman’s. Photo by Lindsey Brown.

Unwashed 2002 rabble, we are not amused.

The other bit of driving solace was supposed to come from my ’74 Lotus Europa Twin Cam Special (aka Lolita). I’ve written a bit about the Lotus here over the years, but there’s far more in my pieces for Hagerty and my book The Lotus Chronicles. It’s a tiny, low, weird, buzzy, crazy, completely un-BMW-like, addictive little bit of a thing, and I absolutely love it. I joke that it’s like being in an abusive relationship, but I’m the one being abused.

I hate to give it a kenahora, in the language of my people, but despite the car having sat for 40 years, it is now pretty turn-key, and the “Lots Of Trouble Usually Serious” thing hasn’t reared its ugly head. Of course, I did spend five years rebuilding the engine, and another two years giving the car a very thorough sort-out, and both of those things did have a lot of drama and expense associated with them.

So if the car isn’t breaking and dying, what’s the abuse?

As I described in the book, there are distinct stages in reviving a dead car. The most dramatic is the first—getting the engine running—but that’s often the easiest (although that certainly wasn’t the case with Lolita). In the book, I itemize thirteen distinct stages:

- Engine starts

- Engine runs and idles for several minutes

- Engine idles indefinitely without overheating or leaking dangerous amounts of oil

- Car moves two feet under its own power

- Car can be driven back and forth twenty feet

- Car can be driven around the block

- Car can be safely driven on short low-speed trips on public roads

- Car can be driven on the highway at traffic speed

- Car can pass state inspection

- Car can be used and driven like a “normal car”

- Car is comfortable

- Car can be driven on long, multi-day trips

- Car is a joy to drive

Obviously, the work involved in getting from one step to the next varies enormously car-to-car. When I bought my Bavaria in Kittery, Maine, in 2014 and towed it home almost exactly seven years ago, I joked that I’d be driving it to the Vintage in a couple of weeks, but its sort-out was so seamless that I wound up doing exactly that, and other than some hot-running issues in 90º temps, it made it just fine. But with the Lotus, due to both the long dormancy and the nature of the car, almost every one of these steps was challenging and time-consuming.

And the last one—”car is a joy to drive”—has been torturous.

Here’s the issue: If you own something like a barn-find ’54 Chevy pickup and all you want to use it for is to drag its barn-find ass back and forth to a local Cars & Coffee, that’s a pretty low bar to clear. You can clock through the steps above and take the exit ramp at “car can be safely driven on short low-speed trips on public roads.” Comfort doesn’t matter, you probably don’t care about full-throttle performance, and you certainly don’t care about handling; that’s not really a feature that was germane to the car even when it was new.

In contrast, part of the reason so many of us love vintage BMWs is that you get to have that cool 50-year-old-vintage-car experience while also having a car that does perform well. Whether you have a bone-stock 50-year-old vintage BMW or one you’ve turned into a track rat, it’s very satisfying to drive it once you make it the best version of what it is, as opposed to the rattly squirmy box of old shocks and worn-out bushings that it felt like before you do all that work.

Now, with a vintage Lotus, take all of that and magnify it. Here’s a car whose niche appeal is largely based on its performance and handling, and those flow from its light, simple, quirky design. So you want to get it right; you want to get it to the point where it drives like a Lotus.

Once I got the Lotus running two years ago and began driving it around on new tires, but still wearing its original 45-year-old shocks, it was a hoot; it’s the kind of car that, when you drive 45 mph on back roads, you feel like you’re getting away with murder. But the suspension was soft as mush, and when I took it up onto the highway, there were awful wheel and driveline vibration issues. A set of straightened wheels, coupled with rounder, higher-quality tires and road-force balancing, almost completely eliminated the vibration issues and enabled me to drive the car at traffic speeds, which was enormously satisfying.

A second round of sorting two winters ago brought a rebuilt front end, adjustable shocks, shorter front springs to lower the nose to Euro-spec height rather than the height resulting from the ridiculous boat-on-plane U.S. federal headlight specifications, and a rear-wheel alignment. With these changes, I started to drive the car harder, beginning to push it on entrance ramps and explore its reputation for being a Lotus with legendary handling rather than being fixated on the fact that it’s something fiberglass and fragile that’s going to break and kill me if I put it sideways. (Of course, the problem is that the car is both.)

The car on its first legal drive in 2019: You can see the front suspension showing a lot of ankle from the springs that give it compliance with arcane Federal headlight-height standards.

The nose is now settled down to where it should be with the new springs.

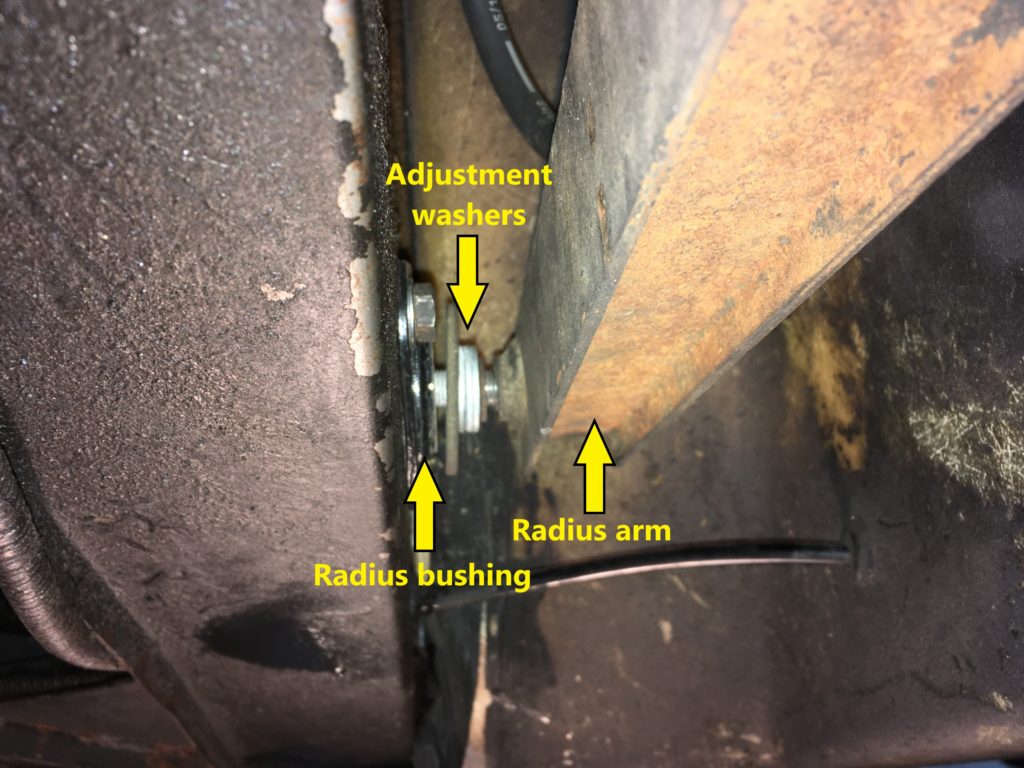

But a vexing issue emerged: On the highway at speed, the car’s lane-changing behavior is odd. Although the steering is go-cart responsive, and the car generally handles very well and very predictably, when you flick the wheel to change lanes, it feels like the nose of the car turns, and some time later, the tail follows it. At first, I was certain that this was a rear-wheel alignment issue; the car’s rear alignment is handled in a very primitive, very simple, and very Lotus way, with spacers (a technical term for washers) stacked between the rear radius (trailing) arms and rubber bushings in the frame.

The specs for the Twin Cam call for a surprisingly large amount of rear toe-in (1/4″ to 1/2″ total toe). I read that the earlier Europas have a more neutral spec (zero to 1/4″ total toe), and that it had been changed due to Ralph Nader’s Unsafe At Any Speed-induced concern about oversteer. By adding and removing washers, I’ve varied the total rear toe-in all the way from 1/2″ to near zero, and it feels a bit less laggy at zero.

The Europa’s odd washer-based rear alignment.

Before the rear-wheel alignment (which was part of the big slug of over-winter work two years ago), the rear wheels were actually toed out, and I wondered if what I was reacting to was having changed it from incorrect-but-familiar to correct-but-unfamiliar. A lot of automotive diagnosis starts off with the question, “What changed?” The problem, however, is that that’s not always helpful. I asked myself over and over whether the car exhibited this behavior before I changed the rear alignment, and the answer was, “First it had mushy 45-year-old shocks and bent wheels and cheap tires that vibrated at over 50 mph, and then it had decent wheels and tires but still had 45-year-old mushy shocks, so I don’t think I wrist-flipped the steering wheel to change lanes, but who knows?”

I hadn’t driven the Lotus since setting the rear toe to zero a few weeks ago, so I took it out for a highway spin a few days ago, and nearly convinced myself that if I wasn’t aware of the history of the lane-changing lag, I wouldn’t feel that anything’s amiss.

But then I drove the other BMWs at the house.

Both of the stiff cars—the M coupe and Louie the ’72 tii with his recent Bilstein HDs, H&R progressive-rate lowering springs, and fatter sway bars—executed snap-of-the-finger lane changes. Even the softer cars—the 3.0CSi, the E39 530i, and the Z3—changed lanes without a hint of feeling like the nose and tail are executing two separate maneuvers.

I’ve been back and forth on a Lotus forum with folks about the problem. The majority opinion seems to be that I’ve either gotten the rear alignment wrong or there’s some other weight-shift issue, like bad engine mounts, causing the problem. I’ve double-checked both and don’t see anything amiss.

I thought about what else it could be.

In the round of work I did two winters ago, I also replaced a leaking rear seal on the side of the transaxle. Doing so requires removal of the large finned nut that holds the seal and goes around the stub axle. This nut also pre-loads the bearing, which affects the side-to-side play of the stub axle. The instructions for replacing the seal are to mark both the nut and the transaxle case (you can see the white mark and a little punch in the middle of it in the photo), count the number of turns to unscrew the nut, replace the seal, and then reinstall the nut the same number of turns and leave it with the marks lined up. I tried to do this, but broke the nut while pressing out the seal. I procured another one, but its threads were not cut the same as the original one, so the marks were useless. According to the manual, the procedure for setting this right involves removing the transaxle, pulling off the cover, and directly measuring the crown wheel and pinion backlash with a dial indicator. I didn’t want to do that then, so I tried to do it by feel.

Last week I found that there was a substantial amount of side-to-side play in both rear wheels coming from both stub axles. I was very excited to find this, since it seemed like it could clearly be the root cause of the lane-changing lag that I was experiencing. I tightened the finned nut and removed most of the play, drove the car, and was surprised and disappointed to find that there was very little change.

The finned transaxle nut holding the seal.

Now, a big part of my whole Hack Mechanic ethos is the idea that you’re so often prevented from fixing things elsewhere in life, but when working on cars, you can diagnose and solve problems completely (e.g., I can’t fix healthcare, but dammit, I can replace my windshield-washer pump! Look at that baby squirt! This is soooooooo great!), so it’s especially irksome to me when I can’t completely fix a problem. I hate the idea of either pulling the transaxle to directly set the pinion backlash with a dial indicator or paying real money for a professional rear-wheel alignment, when I don’t in fact know whether either will solve the problem.

I had another idea. I floated the idea on a Europa forum that the fact that I’d replaced the front springs with shorter and stiffer ones but had left the rear ones stock could be the cause of the problem. The consensus was that this didn’t seem likely (the front springs were only slightly stiffer), but I tried something: Since the shocks are adjustable with just a twist of a screw, I set the rears to the stiffest possible setting and drove the car again.

Lane-changing still doesn’t feel as seamless as it should, but it’s now noticeably better.

Maybe next winter I’ll let Lolita spend some time on the lift, pull out the transaxle, set the pinion lash correctly, and replace the rear springs as well. But for now, I think I’ll let things be, stop obsessing about it, and try to enjoy the car.

At least until it abuses me again.—Rob Siegel

Signed inscribed copies of Rob’s new book, The Best Of The Hack Mechanic: 35 years of hacks, kluges, and assorted automotive mayhem from Roundel magazine, are now available for pre-order here and will be available on Amazon by the end of the month. His seven other books are all available on Amazon, and signed copies can be ordered directly from Rob here.