It was a gorgeous late September afternoon at San Diego’s La Jolla Independent BMW Service. Two new front brake calipers sat on a workbench, next to pads and rotors in boxes. My beautiful Rubinrot (Ruby Red) 7 Series sat on a lift behind me while I took off a glove to check my phone. It had been about twelve hours since the car and I were to have departed on our way east, through deserts and canyons across the vastness of North America.

Instead, the big 733i was in the air, four wheels removed, with its brake system sitting on a workbench.

[Editor’s note: This article was originally published in Roundel magazine, and we encourage you to view it in print as well.]

A year before, taking a 40-some-odd-year-old, non-running 733i from San Diego to Greenville, South Carolina, in three days, solo, in time for the 50th-anniversary BMW CCA Oktoberfest would have sounded like a great (if asinine) Roadkill episode, and that’s about it. The idea that I would end up in a race against time, learning to fix the car myself, would have been ridiculous.

If this were a film, there would be a foley record scratch and a freeze frame about now, since—let’s face it—I never intended to own this car. The big Seven came into my life with a call from my good friend, enabler, and fellow E24 enthusiast Mike Perlman, who spotted a deal on a cheap E23 and asked if I wanted to split the cost. If you’ve had any sympathy for the ordeal up to this point, let it be dispelled by the fact that I agreed instantly to buy half of a 40-year-old 7 Series in Los Angeles, 2,300 miles from my home in South Carolina, based on a Craigslist ad with one photo. But somehow, for less than the cost of a set of tires, we owned a 1979 BMW 733i.

Our idiocy was made less idiotic by the trunk full of spares and documents that came with the car: delivery paperwork, photos of its bare-metal repaint and maintenance in the early 1990s, period BMW workshop manuals specific to the early E23 chassis.

Rubinrot is an inspiring color, no matter the backdrop.

BMW enthusiasts generally have lists of items to refresh when purchasing a car. This list varies from model to model, but usually includes fluids, gaskets, batteries, and bushings—a healthy range of reasonable and easy maintenance. We looked at our 733i and decided that the best course of action was, to paraphrase those shoe guys, just drive it.

After all, it drove fine; I used it whenever my job brought me to LA. Perlman drove it to work a couple of days each week, and to Los Angeles Chapter BMW CCA shows on the weekends. It made numerous trips to Santa Barbara to visit my girlfriend; it appeared in a music video. Wherever it went, our big red Seven brought pastel tones and 1970s charm to everyone it met.

Everyone, that is, except online auction site Bring A Trailer, which slapped our Seven with a rejection letter when we finally decided to list the thing.

So we kept driving it, until one day it came to rest in its Glendale parking structure and felt disinclined to restart. I think that the idea to drive the car east started as a joke, but the concept was born: With a one-week window between work trips for my media-production company, I could have the car in Greenville, South Carolina, in time for the 50th BMW CCA Oktoberfest celebration!

Perlman, to his credit, didn’t bat an eye at the plan. It definitely did him a favor; with four cars and two parking spaces in Glendale, keeping a broken Seven around wasn’t ideal. One moderate buyout and a 200-mile AAA tow later, the car was in San Diego at La Jolla Independent.

The 733i arrives at La Jolla Independent BMW Service, rife with fuel delivery issues.

For those of you who love ’80s cars and see cheap old E23s on Craigslist, let me beat you over the head with some knowledge: an early-production 733i is not an E28, an E24, or a late-M30-powered BMW. It’s a 3.2-liter experiment, a thermal-reactor-equipped E12-era headache, and La Jolla proprietor Carl Nelson never let me forget it.

When you ask shop owners around the country about Carl Nelson, they tend to say the same thing: He has forgotten more than you and I ever learned. Minutes of diagnostics with him are days for you and me. If there was a first moment of awe, it was when Nelson told me, from memory, which terminal on the Bosch combination fuel pump/main relay to jump to run the fuel pump directly (it’s 88D, if you’re reading this while stuck on the side of the road in your 733i).

It’s worth mentioning that none of this trip would have been possible without the technicians, guests, friends, and passing experts who make La Jolla Independent unique even in the oddball world of BMW service, because this car put up a fight. Even after a new fuel pump relay (a model-specific early-E23 item), a functioning fuel gauge, and a couple of gallons of fuel got the car started, there was a lot that needed to be done. The thermal-reactor system—a super-heated liability that can crack the cylinder head—had to go in favor of a more traditional emissions setup. JP Hermes, whom you might recognize if you’re in any “Vintage BMW Parts” Facebook group, dug up the appropriate manifolds and corrected my amateur sandblasting and spray-paint work. Kaelin Thompson and Konstantin Krapiva dived into the vacuum nightmare and started to gradually reorganize the engine bay to a more efficient state.

A simple victory; the 7 Series makes it a block down the street in La Jolla, California, under its own power.

The real adventure started the morning I was supposed to leave. I like to think of it as something like the reactor-explosion scene from the miniseries Chernobyl; one of the techs had started to check the power-steering-fluid level—ten or twenty pumps of the brake pedal, a process familiar to any vintage-BMW owner with a hydroboost system—when, as pressure built, the brake master cylinder began to spew fluid. I was handed a new-old-stock (NOS) replacement master cylinder (somehow located by ESP and quickly pulled from Nelson’s deep stockpile of parts) and pointed in the direction of the toolbox: Get on it, kid.

A replacement brake master cylinder was step three of, well, more than one can recall.

Later, with my first master-cylinder replacement done, I ran the numbers: I could make it to Phoenix by six, or Albuquerque by midnight. All that was left was a fresh brake bleed, and the Seven and I would be home free. But it was not to be; when we went to bleed the system, we found the drain bolts on both front calipers seized. Dread began to dawn as I realized that we would need to order calipers, delaying departure again.

Except we wouldn’t.

If you need it, Carl Nelson has it.

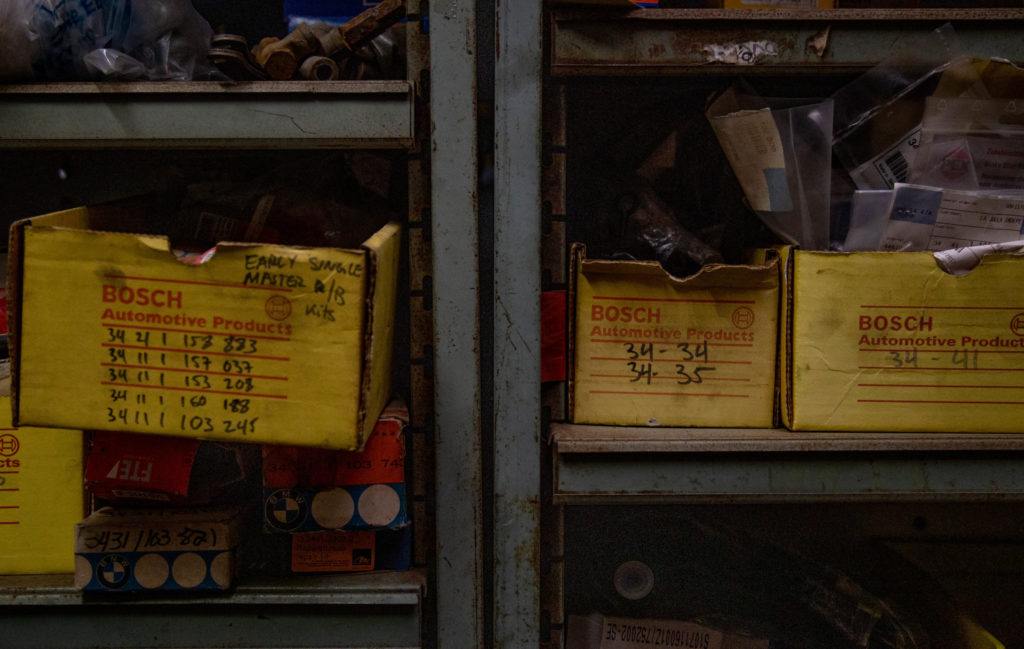

Nelson recalled a part-number category and sent me across several bays into the La Jolla Independent parts department, a series of lift-sized garage bays stacked floor-to-ceiling with Home Depot shelves and row upon row of vintage BMW parts. In the braking section (directly above rotors and pads) was a set of shiny new calipers in E23 fitment. It was the beginning of the realization that this crazy initiative might actually be possible, if only because of the awe-inspiring shop at which I found myself marooned for another night.

By noon the next day, with new calipers, rotors, and pads, and with new fluid pumped in, the car was finally set on the ground. With all the brake work, we hadn’t even started the engine since getting the car running and coaxed onto the lift.

This would prove to be a mistake.

This time it was a green glint from the corner of the radiator—unrepairable, at least on my schedule. The group gathered around the Seven, eager to finally be rid of its incessant repairs, knew that this was a departure-killer. Of course the radiator was early-E23-specific. But again, Carl Nelson surprised us: He had one radiator that had been sitting, by his recollection “for thirty years”—another NOS unit, buried under piles of shipping boxes and cooling systems for every BMW imaginable. Sure enough, it was specifically a 1978–’79 Genuine BMW 7 Series radiator, dusty but complete.

If there’s a radiator in there, Carl Nelson will find it.

I dived back into the project as the sun set. Time was running out; my leisurely six-day trip across the American West had turned into a three-day Cannonball Run. Every hour I spent working now was one less hour I could sleep between driving legs. Finally, at 8:00 p.m., working under the overhead shop lights, we got the car started again, this time for good. As we ran through the systems, things started to finally look up. The brakes felt great; the power-steering pump was grumpy, but functional; the car held its temperature, even with the air-conditioning on.

We had brought the Seven back to life and located rare NLA and year-specific parts, and the farthest I had to walk to do it was down the street for lunch.

The 7 Series is joined by a more colorful companion.

That is, until our second startup, when the A/C disappeared, replaced by heat from the defroster. One of LJI’s visitors that evening was Australian BMW collector and expert, Michael McMichael, who broke the news to me carefully: Unlike other cars of the era, the E23 used a vacuum system to operate the HVAC, and if any single vacuum bladder failed, it would default to heat via the defrost vents. Despite the general agreement that the car had “60-2 air conditioning” (60 mph, two windows down), Nelson paused and examined the cowl.

As it turns out, that complicated vacuum system funnels into an air valve visible in the engine bay—an air valve that can be fooled by other sources of vacuum, like the blocked-off vacuum lines we had cleaned up two days before. With engine vacuum running into the HVAC valve, the system was tricked; it was still limited to the defroster and under-dash vents, but the air coming out of those was icy cold. Carl Nelson had hacked the system, and that was good enough for me.

A hastily-fastened radiator hose becomes a quick-release overflow valve leaving San Diego County.

After all that, the drive itself seems underwhelming. It certainly didn’t go entirely smoothly; a lower radiator hose, fastened by Yours Truly, blew off 50 miles into the drive, resulting in a return to LJI and a coolant flush, and there were idiosyncrasies here and there. But the M30 up front hummed like a single-engine propeller motor, its three-speed automatic holding desert highway speeds with confidence. Gradually my tension melted away, replaced by the highway bliss that a BMW always provides.

The 7 Series has always been a spectacular road-trip car. The E24 and E28 Fives are comfortable in a mechanical sense, but in the Sieben, there’s an added element of ease and isolation that reminds you that this is something finer, refined and elegant. It’s one of the few truly classic cars that feel so sturdy and isolated inside, and even with the air-conditioning pumping through half the available vents, it was the most comfortable I’ve ever been in a car built before 1990.

The 7 Series, smug and victorious, at the BMW CCA National Headquarters in Greenville, South Carolina. Photo by Tucker Beatty.

True to form, I made it to South Carolina in three days, with overnights in New Mexico and Louisiana. The longest day was the second, covering 1,184 miles in seventeen hours before pushing through on the third to roll into my driveway at midnight.

I’ve driven to O’Fest before, including a run from Boston to Monterey in 2016. By mileage and time, that was a longer drive. But this trip captured so much more of the spirit of the BMW CCA; it was adventure in the purest sense, made possible by a community to which I will be forever grateful. The magic of the BMW CCA is the way it brings together knowledge and ambition, putting the enthusiast in contact with brilliant minds that can make a dream possible—even if that dream is a stupid, stupid idea.—David Rose

[Photos courtesy David Rose, Tucker Beatty.]