The majority of BMW owners have no idea what their engines or the underside of their cars look like, because they rely on professional shops to maintain and repair their vehicles—and that’s certainly okay. But personally, I think that at least some of them are missing out on what I consider an important and satisfying part of the BMW experience: doing it yourself. Judging by the conversation when two or more BMW CCA members get together, many of our fellow club members feel the same way, and that’s great, because other club members and BMW enthusiasts in general are a great source for the technical knowledge on which many of us rely to keep our rides running without taking them to the dealer.

With a little help from our friends, and especially with the explosion of BMW-related information available online, many more of us are able to know the sense of accomplishment that comes with successfully completing something as simple as an oil change, or as complicated as a clutch-and-transmission replacement. All it takes is the aforementioned information, a safe place to work, the right tools, and the correct parts.

Most of the time.

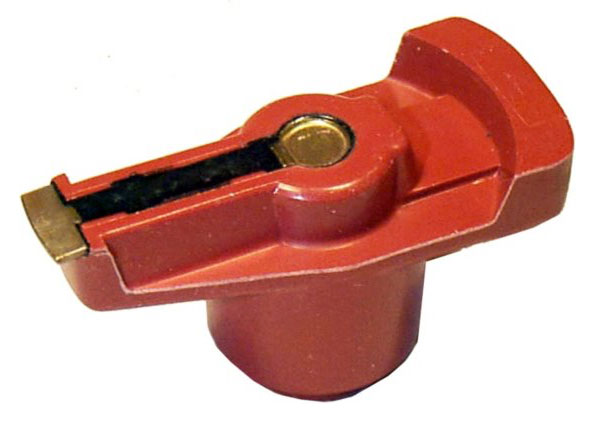

In the pantheon of car repairs I have performed over the years, I can rank them from easy to hard. I think back on one such event many years ago that would have been so very quick and easy—if I had the right part and a well-lit, warm, dry, safe place to perform the repair: I was returning home from work late one night—it actually was a dark and stormy night—when about five miles from home, my 2002 died and would not restart. It turned out that the metal contact on the rotor arm under the distributor cap had separated from the centrifugal-advance mechanism so that it no longer contacted the rotor cap; ergo, no spark.

So there I was in the dark, on the side of a fairly narrow road, and I was fresh out of spare rotors. Did I mention that it was also raining? I don’t remember why I had a tube of super glue in the car, but I was able to bend the contact back into place and secure it with the glue, and it held together long enough to get me home that night. From then on, I carried a spare rotor and cap in the car, along with a spare water pump and fan belt—and naturally, I never needed them again.

You don’t see many of these anymore.

Even with the rain and darkness, it was still one of my easier fixes. I can’t say the same for the time my E36 M3 race car blew a head gasket during my first-ever BMW CCA club race at Lime Rock.

That episode taught me about compression and leak-down tests, failed thermostats, and how to rebuild an S50 cylinder head. The garage was warm and dry, the parts were readily available, and I had the right tools—after ponying up for a couple of necessary BMW specialty items.

My most immediate requirement, though, was knowledge, which I did not have when I started the job.

A stuck thermostat caused the engine to overheat.

What I did have was a Bentley E36 manual, a BMW TIS CD, and most important, a friendly BMW expert whom I could telephone; he would walk me through the foggy parts. I know his advice was excellent, since I finished the job in 2002, and seventeen years of racing later, the engine is still running well. Yep, that was the hardest repair—and still the one in which I take the most satisfaction.

A DIYer’s best friend.

The most recent fix on my M3 turned out to be the easiest, although I didn’t think it would be at the time.

During the last BMW CCA club race at the 2016 Historics at Pitt Race, I came up out of Turn Five at full throttle. It was a right-hander in which everything was trying to torque to the left, and only the tires kept the car turning right. Nearing the rev limiter, I expertly shifted from third to fourth—

Except it wasn’t fourth. It was second.

It’s what they call the money shift—and my first over-rev in more than two decades of driving the M3. Sure, I had the clutch to the floor in less than a second, but I feared that the damage had been done, and I still didn’t know why the drivetrain had twisted, causing the missed shift. As I finished the lap under reduced speeds, the engine sounded okay, but I couldn’t escape the dread that I would soon be learning more about engine internals than I ever wanted to know.

Logistics, time, and lack of workspace prevented me from analyzing the cause of the mis-shift for some time. I suspected broken engine mounts, broken transmission mounts, a broken subframe, or a combination of those. Any of these would cost me time and money—maybe lots of money.

But when I finally got under under the car, the most incredible thing happened: I discovered that the cause of the drivetrain torqueing far enough to put second gear where fourth should have been was one missing nut on the bottom of the left motor mount. How it happened is still a mystery, since I checked the torque on the nut before the race.

The easiest—and cheapest—fix.

The fix was a new flange nut that cost under two dollars and needed only a torque wrench to install, so it was the easiest fix ever. I later put in a set of new BimmerWorld racing motor mounts just to make sure—using new fasteners, of course.

But what about the engine? According to my data acquisition, it had hit between 8,100 and 8,200 rpm for a fraction of a second, so roughly a 1,000-rpm over-rev. Compression tested okay, and a few laps around Heartland Motorsport Park working up to about 7/10ths did not raise any red flags, so last July, I rolled the dice and ran the Historics at Pitt Race again. The M3’s motor felt and sounded great, and by the end of the weekend, I had equaled my best lap times from two years earlier. I did shift with great care and precision, especially coming up out of Turn Five, but by Sunday, everything felt normal again. It was a tribute to the abuse that this particular S50B30US engine could take.

Pitt Race 2018, and the M3 ran great. It’s front row center here.

When it comes to working on your car, I guess the moral of the story is that if I can do it, you can do it. Sure, I’ve collected a bunch of tools over the years, and building and maintaining a race car will teach you a lot, but two wrenches, a floor jack, and some jack stands is all you need for an oil change.

The point is, thousands of BMW enthusiasts work on their cars not just to save money, but because it can be fun. And the satisfaction? Well, that’s priceless.—Scott Blazey

[Photos via Alex Tock, Brett Sutton, ECS Tuning, Bentley Publishing.]