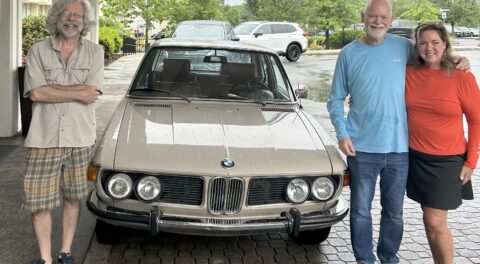

[There’s a lot going on right now at Rob’s House of BMWs, Pain, and Not Enough Space and Money. I floated the Bavaria I’ve owned since 2014 for sale on my FB page, got interest but no offers, and was in the process of listing it on Bring-a-Trailer when a lovely couple from Alabama who have bought two cars from me swooped in and claimed it. As part of putting together the provenance of the car, I did some searching on my laptop, and found this article that I wrote and submitted to Satch as a Roundel piece, but for reasons I don’t recall, it wasn’t run. So I present you, from June 2014, The Incredible True Story of Birgit the Wunder Bavaria:]

Who’s to say why we’re attracted to what we’re attracted to, why we love what we love. With cars, there are certain slam-dunks—who doesn’t love a ’63 split-windowed ‘Vette or an E-type—but take one step outside that circle and you’re into questions of personal taste. Muscle cars do nothing for me. Don’t get me started on SUVs.

But a Bavaria, well, now you’re talking.

The body code for the big BMW four-door sedan built from 1968 through 1976 that preceded the 733i was E3. The 2500, 2800, 3.0S, and 3.0Si sedans were all E3s, but in the U.S., most of the E3s sold were labeled as Bavarias. A perfectly proportioned luxury performance flagship aimed right at the heart of the Mercedes lineup, you could come very close to sketching the Bavaria, never having seen one, if you visually interpolated between the small two-door 2002 sedan and the big two-door E9 (3.0CS) coupe. The E3’s interior is absolute perfection in early 70s German industrial design, with a clean uncluttered dashboard and the same greenhouse of windows as the 2002 and 3.0CS, but with room for five and a cavernous trunk. While not being as tossable as a 2002, the E9 brings out your smile with power and torque from the legendary M30 engine, a power plant that was in production for 28 years. Bavarias languished in the market for a long time as bastard stepchildren living in the shadow of their fair-haired siblings, but they are now beginning to get their due, as they provide a similar vintage driving experience to their high-dollar family members for a small fraction of the cost. Mechanically, they’re very similar to E9s, sharing the drivetrain and much of the braking and suspension systems. Unfortunately, since they also share the bred-in-the-bone family trait of rust, it’s difficult to find a clean one. The idea of adding a Bavaria to my E9 and 2002tii to complete the set of BMW’s early 70s US cars was irresistible.

So the following Craigslist ad certainly piqued my interest:

“This is an exceptional original 1972 Bavaria. Color is Sahara with brown interior. Paint and interior are original. 3.0 liter 6 cylinder motor runs beautifully smooth. No known modifications. Originally a California car, and it shows—the body is like no other unrestored Bavaria in the East. 49k miles. $xxxx.”

The ad featured two poor pics of a car crammed into a storage area from which I could tell very little. I called and learned that the car had been owned for many years by an enthusiast in Portsmouth, NH, who’d brought it in from California and showed it at minor Northeast events. He’d passed away in the mid-2000s, and the car was put into storage. It was purchased about five years ago by the gentleman who ran the ad. He stressed that the car was a rust-free and in excellent overall condition, though not currently drivable. It sounded interesting, but the colors and breezes of a glorious New England fall tempted me into buying a $3,000 Z3 instead. That made nine cars. I reasoned my way out of following up on the Bavaria.

Until a friend of mine, Wink Cleary, posted a link to the Bav’s Craigslist ad on the Nor’East ‘02ers Facebook page, asking “Does anyone know this car?” I told Wink that, while I hadn’t actually seen it, I’d spoken with the owner, and it sounded quite interesting. “Well,” he said, “I have an appointment to see it Friday night.” I had that pang that comes from having passed on something and learning it was gone, but, hey, $3,000 Z3, right?

So, Friday night, I message Wink and asked, “Did you go see the Bavaria?” No response.

Saturday night, I messaged Wink again, “Did you go see that Bavaria?” Again, nothing.

Sunday, I messaged Wink “DID YOU GO SEE THAT BAVARIA OR DO I HAVE TO GO UP THERE AND BUY IT OUT FROM UNDER YOU HAHAHAHAHAHA?” Wink replied that, unfortunately, his wife’s minivan had just died, so instead of looking at the Bav, they had to go buy a real car.

Hmmn.

So, with the passion and fervor that a second chance brings, I called the seller, reintroduced myself, re-asked the rust question, and was told again that the car was a genuinely rust-free former California car. I stowed my skepticism and planned to see it the next day.

The car was in a warehouse just across the New Hampshire border in Kittery, Maine. The owner warned me that he was in the middle of a business deal and might be on a conference call on his cell. Sure enough, when I arrived, he pointed at the phone in his hand, rolled his eyes, and let me into the warehouse. G-chunk went the big overhead lights, illuminating not only the Bavaria up on a lift with the wheels off, looking something like a levitating beached whale, but also two 2002s and at least six boats, all crammed in at random angles. The owner wordlessly handed me a drop light and went back outside to his car to finish his call.

Bavarias do not look particularly graceful on a lift with the wheels off.

Alone in the warehouse, with the Bavaria up on the lift, I could inspect the undercarriage thoroughly with the drop light. And what I saw took my breath away. Not only wasn’t there a rust hole, there wasn’t a rust bubble on the undercarriage, rocker panels, door bottoms, anywhere, just a trivial amount of surface oxidation on the frame rails and floor pans. I made a mental note on the credit side of the ledger for what appeared to be brand-new calipers on all four corners, and on the debit side for the fist-sized hole in the muffler and the failed driveshaft center support bearing.

Perfectly intact rockers.

Perfectly solid floor pans.

I lowered the lift and looked at the car’s body panels—all dusty but intact. Sahara (tan) is far from my favorite BMW color, but the body looked clean save a few nicks and chips. And the brown interior. My lord. Perfect vinyl seats (which, unlike vintage leather, wears like iron). Perfect headliner. Perfect rugs. The original bus wheel and wood shift knob. One small dash crack. All original but for a late 70s Blaupunkt cassette deck.

Yum, right?

I would neither buy nor not buy a car for its headliner, but… holy cow.

The owner got off the phone and came in. We immediately hit it off. He told me about his three 2002s (there was a third one he said he hadn’t seen in ten years in a warehouse in Chicago, a story I was dying to hear), how his business dealings were cramping his passion, how he’d just replaced the Bavaria’s calipers but didn’t have time to finish sorting it out. I mumbled in adoration of the car’s overall condition.

“Any provenance on the low mileage?” I asked. “A folder of receipts?”

“Not really,” he said. “The owner died. I bought it from his estate.” In cases like this, you try to infer the plausibility of the mileage from the condition of the car. Given the complete lack of rust and the intact interior, sure, I thought, it could have 49,000 miles. Or it could have 149,000.

“Can I hear it run?” I asked.

“Sure,” he said, “I start it every six months or so.” We jumped it, but it wouldn’t start due to the float bowls having run dry. I pulled the top off the air cleaner to give it a blast of starting fluid, and smiled to see not the original miserable Zenith Strombergs but the pair of the Weber 32/36 DGAVs that every enthusiast would install. The big straight three-liter six immediately snorted to life and settled into a nice even idle. It was, shall we say, throaty due to the exhaust hole, but there was no oil smoke, no antifreeze smell, and no Valdez-sized puddles of fluid. Damn. Rust-free and apparently has a good engine.

“What do you need to get for it?” I asked. (Pro Tip: Always ask this question. You’ll sometimes be stunned what people say.)

“Well,” he said, “I’ve been reading your stuff in Roundel Magazine forever. I love the idea of the car going to you. For you… [says a number less than $xxxx].”

My left and right brain hemispheres briefly battled as I tried to get out the next words. Right brain: “I totally want it,” I said. Left brain: “But… this will be my tenth car. I have nowhere to put it over the winter. And it’d be a crime to let it sit outside.”

“Tell you what,” he said. “Give me a hundred bucks, and I’ll hold it for you ‘till spring. You can even come up here and work on it if you want. You can change the center support bearing while it’s up on the lift.”

Okay. Well then. Having seen the ad, talked with the guy, driven up there, verified that the car was completely rust-free, heard it run, and been given this option to put only a hundred bucks at risk for over-winter storage and a potential place to wrench, how are you supposed to not do that? You’re not. You walk away from that, and every bit of car karma will break the other way for the rest of your life. Hondas will eat valves. Camrys will crack subframes. So I did what any one of you would do—I gave the guy a hundred bucks and began bragging that I’d just bought a rust-free ‘72 Bavaria for Subaru money.

Over the winter, I did some web-sleuthing. It’s a small vintage BMW world after all, and the simple act of searching on a car’s VIN often reveals surprising things. However, I had no luck on the VIN, and a search for the deceased owner’s name and “Bavaria” yielded but a single hit from 1991 on a [now-defunct] E3 web site [SeniorSix.org] saying how much he was enjoying the Webers and the new radiator. HTML immortality is such an odd thing.

I ordered a new center support bearing, thinking I might take him up on the offer to work on the car on his full-height lift (I have only a mid-rise lift at my house). Then I thought, gee, to replace the bearing, the driveshaft has to come out, and to do that, you have to drop the exhaust, and the muffler has a hole in it; the smart move would be to buy a new exhaust too. Then I learned the exhaust is a dealer-only item which, front to back, costs nearly a grand [and is now unobtanium].

And then I suffered a precipitous reduction in my hours at my real-world job. Suddenly, the Bavaria—whim-able money when I was working full time—represented real coin.

I worked on other car projects over the winter, always conscious of containing costs. In mid-May, I heard from the Bavaria guy. “So… when do you want to pick up your car?” A fair question. With too many cars and not enough income or space, I entertained walking away. Then I thought, no, my reasoning was probably sound. I’ll rent the U-Haul transporter, drive up there with the Suburban prepared to pick it up, and if I see a deal breaker, I’ll just forfeit my deposit.

When I got up there, the car was down off the lift and sitting outside on dry-rotted tires and steel wheels with cereal bowl hubcaps. In the sun, I noticed some overspray on the paint. Closer inspection revealed some spots of black primer under the hood, and some non-original welds holding on the nose. It was likely the car had been cracked in front at some point, and the nose, hood, and fenders replaced. Still, the work appeared to have been fairly well done. As it had in the dead of winter, the car started immediately when I turned the key. And seeing that interior in the sun… the car still gave me a great vibe.

I thought, yes, I’m being careful, yes, I’m being responsible, but yes I’m totally going home with this car. To pass on it would be the irresponsible act. I gave the owner the money. I even had the completely audacious thought that I might drive it to The Vintage—the BMW event in Winston-Salem being held in 12 days. I put the car in gear and eased it onto the trailer.

This eleven-year-old score still feels sweet.

And that’s when I noticed—no power steering, no power brakes. My Vintage dream fell earthward, like Icarus (“Gee, this car was much easier to sort out than I expected”—said no car guy ever).

But I then got to engage in one of the satisfying rituals of picking up a car—the call to Hagerty insurance. The conversation, which I swear I am not making up, went like this:

“This is Rob Siegel. I have several cars on a policy with you. I just bought a ’72 BMW Bavaria and I want it covered for the tow home.”

“Okay, Mr. Siegel, will the car be garaged at the same location as the others, same usage?”

“Yes.”

“What agreed value do you want?”

“Um, [spitballs a number slightly more than $xxxx].”

“Just a moment… Mr. Siegel, the annual increase to your policy will be $31.”

“I LOVE you guys!”

Now, even though we say it’s “condition condition condition” with cars—that what matters is the body, the paint, and the interior, and that the mechanicals are comparatively unimportant—that doesn’t mean it’s quick, easy, or cheap to sort a car out mechanically. Despite the Bav being completely rust-free, I was taking a boatload of risk buying it without driving it, and to have the first lurch onto the trailer reveal a lack of power brakes and power steering was not a good sign. New E3 power brake boosters are unobtanium, and rebuilds are expensive.

The Bavaria immediately looked at home in my driveway with the 2002tii and the E9. I began referring to them as “The Nixon-Era Triplets.”

Step one in a sort-out of a long-dormant car is a fluid change. Running a car for any length of time without knowing how long the oil’s been sitting in there gives me the heebie geebies. While the car is up, I’ll change the transmission and differential fluid with Redline, since it’s not unusual to find cars where these fluids smell like they’ve never been changed. I’ll typically judge if the brakes and cooling system are functional before I purge their juices, since if these systems need to be opened up to replace any component, there’s no sense in purging them twice (in the Bav’s case, the brake fluid had been renewed as part of the caliper replacement). I’ll inspect the cooling hoses and fuel lines, giving them all a squeeze. If they’re leaking, I’ll address them immediately; if they’re soft and pillowy or rock-hard, I’ll order new parts and move on for now. I’ll also look at the antifreeze to see if it’s obviously discolored, and I’ll rock the fan back and forth to feel if the water pump has any obvious axial bearing play. The Bavaria passed all these tests.

The Bavaria “assumes the position.”

Of course, the other fluid of consequence is gas. On cars that sit, the gas turn to varnish and the gas tank spontaneously generates a stew of rust. You can drain and drop the tank and clean it out, or you can remove the sending unit to inspect for rust and risk it not sealing when you reassemble it (been there), or you can take the easy way out and run the engine for a bit, then remove and slice open the fuel filter and see if it looks like it’s trapping metal mud, and if not, assume you’re good. I did the latter, replacing some original 42 year-old cloth-braided fuel lines.

The center support bearing was completely detached from its bracket.

Once fluids are addressed, I adjust the valves. On a vintage BMW engine, this also gives a chance to verify that the banjo bolts holding the oil distribution pipe are tight. If these loosen, oil doesn’t reach the front cam lobes, sometimes resulting in wear so severe that the valves may barely open. But all looked good.

Now, on to play the hand I’ve been dealt. There’s a filter hidden inside the power steering reservoir. If the filter has never been changed, it effectively turns to stone and prevents hydraulic boost. But when I opened the reservoir, I found it completely dry of fluid. Oh, I thought, I know the name of this tune—it’s empty because the system is leaking. I’ll fill it, and it’ll pee all over the garage. Still, it’s what you need to do to find the leak, so shoving a basin beneath it, I filled the reservoir, started the car, turned the steering lock to lock, and… it worked perfectly with no leak. It can’t be this easy, I thought. Surely it’ll leak out in the next few hours. Or days.

Nothing.

Okay, then, power brakes. Again, try the easy stuff first. The hose connecting the booster to the intake manifold looked original, with one end frayed. I thought it could pose a potential intake leak, so I cut it off clean. I then tested the hose’s one-way check valve by removing it and blowing into it in the direction it should allow air to pass. It didn’t. I thought, I wonder… and turned the valve around and blew. It worked. It had been installed backwards. With it reinstalled correctly, the car had power brakes.

Right. I’m liking the vibe of this sort-out. Let’s knock off the center support bearing, drive this puppy, and see what it really needs. Normally, knowing the exhaust has a hole in it, you’d just take a Sawzall to it and install a new one, but because I hadn’t yet solved the issue of the thousand-dollar exhaust, I didn’t want to destroy it. I tried to disconnect the resonator from the headpipes and muffler, but the whole thing was one solid rusted mass. Fortunately, no part of the Bavaria exhaust goes above the rear subframe, so I was able to drop it intact. I replaced the center support bearing, put the driveshaft back in, and thought let’s just reinstall the exhaust for now so I can get the car inspected, perhaps then drive it to a muffler shop. I looked at the hole in the muffler, and thought, hmmmmn. I measured it, drove to Home Depot, bought a section of chimney pipe, cut it to size, clamped it around the muffler with four big hose clamps, and re-installed the exhaust.

This really was pretty bad.

And the chimney-pipe trick worked so well that I used it years later on the muffler on my E9.

Poof. The car was drive-able. The tires were still rolling dry-rotted danger, but the sorting-out process involves taking small steps and seeing what the car does. I drove it around the block, first gear, tap the brakes, yup it stops, first to second, come to a stop, do it again. Astonishingly, there wasn’t anything glaringly wrong with it. The clutch worked. It revved easily and shifted smoothly. It steered and stopped straight. There were no screeches, klunks, or rattles. In fact, the car was almost eerily quiet. Compared with my Bilstein’d and sway bar’d E9 and tii, it was a bit floaty and boaty, but I loved it. And the feel of the big early 70s German interior was everything I remembered.

I did a quick check of the electrical system. If the alternator and regular are working correctly, a voltmeter should show about 14V across the battery when the engine is running, but the car put out only 12V, indicating either a bad alternator or regulator. This is an old-school car with an external regulator, so I tried replacing it first. A spare regulator got me 14.2V. Done.

I had some original alloy wheels off a BMW 3.0CS that look the bomb on a Bavaria, but their tires were only marginally better than what was on the car. Fortunately, 195/70R14 rubber is cheap, and for $250 The Tire Rack sent me a set of Sumitomos. Once the new non-homicidal rubber was mounted on the alloys, the car could be driven further than just around the block. I took it up onto the highway one exit. It had plenty of power through all four gears, but the temperature climbed rapidly past the 2/3 mark. This was not surprising, as vintage BMWs typically need a new radiator, water pump, fan clutch, and thermostat to be dependable (and, no, replaced in 1991 doesn’t qualify as “new”). I got it home, drained the coolant, popped the thermostat cover, and found the thermostat was encased in semi-hardened green coolant snot. Further, the thermostat itself was wrong. Because these M30 engines had such a long production run, there’s a lot of mixing and matching of ancillary engine components. There’s an early and a late thermostat, and an early and a late thermostat housing. Both thermostats will physically fit both housings, but if they’re mixed and matched, the thermostat won’t open and/or close correctly. It turned out that, in addition to the green goo, someone had installed the late thermostat in the early housing. I replaced it with a correct 71-degree early thermostat, flushed the coolant, removed every hose, scraped all the corrosion off all the coolant necks, buttoned it up, and tried it again. Repeating the one-exit test, it ran between 1/3 and ½ up the gauge, so I drove it about 30 more miles. It stayed cool.

This was nasty.

Holy shit. This car was much easier to sort out than I expected. I waited for lightning to strike me dead. It didn’t. We’re going to The Vintage. I began calling her Birgit The Wunder Bavaria.

Now, there’s a chapter in my book called “How To Make Your Car Dependable (well, more dependable).” In it, I strongly recommend prophylactically replacing the entire cooling system of a car on which you wish to depend. But, with less disposable income to throw around, I thought I’d try doing it a different way with the Bav and not drop $800 on parts I had no direct evidence were needed. What’s the worst that’ll happen? The car dies and I bail on the trip. When I mentioned this to Maire Anne, she raised an eyebrow, paused, and said “I’m surprised” (nice to know she listens to my automotive babbling). I adopted this same pose with the ignition, inspecting the components but not replacing a single part. The car did have torn boots on the lower control arms, but nothing was loose, and new parts weren’t orderable within my time frame anyway, so I ran with what I had. I did, however, order a new water pump to have with me on the drive down, and I packed spare used ignition parts, a fuel pump, and even a spare battery (the small one from my tii) in case the alternator died.

Having crossed the Rubicon, I felt honor-bound to give the car a quick exterior wash and interior wipe. While falling well-short of a detailing, she transformed quickly from just-out-of-storage wallflower to looking ready for her coming-out party. As I was wiping down the door jam, I found a 1980 service sticker from a California shop, providing some documentation of the car’s purported California provenance. Unfortunately, the mileage listed on the sticker was 60,000, showing that the odometer isn’t 49,000 miles, it’s 149,000. In a sense, this was the last petal falling from the flower of the original ad (the others being that the car had been hit, had been repainted, and had been modified). But it really didn’t matter, because after living beneath the car for ten days, it was, in fact, every bit as rust-free as I’d thought (said no car guy, ever, until me). And, while cleaning out the trunk, I found a Haynes manual, the back page of which listed certain service events, including, to my sheer delight, “engine rebuild 123,010 miles.” Sheesh, I thought, no wonder the engine runs so well.

The rest of the sort-out was small stuff. I readjusted the Webers’ aftermarket linkage to allow the second barrels to open. The left front wheel bearing was loose enough that, rather than worry about it, I replaced it. I swung for the fence and tested the a/c by pressure-testing the system with nitrogen, but to no one’s surprise it was leakier than O.J. Simpson’s alibi. I then addressed some cosmetics that bugged the hell out of me. The car had the wrong center grille, so I borrowed the one from my 3.0CS (yes, I used my $30,000 car as a parts car for my $xxxx car). The cigarette package-sized group of four window switches kept falling out of the door card. I extended the tabs holding them on.

Yes, I used my E9 as a parts car for my Bavaria. Just this once. Okay, it happened more than once.

The 800 mile drive down to The Vintage began at 5 am in rainy weather, so the car ran cool. But as the skies cleared and the temperature hit the high 80s, the water temp did in fact exceed the pucker threshold of 2/3 of the way up the gauge when I tried to hold 65 mph up hills. My caravan companion Tom Samuelson offered that it took him multiple tries to get all the air out of his cooling system and wondered if that could be the source of my woes. I cracked open the Bavaria’s coolant bleed valve but nothing came out. Surmising that some corrosion might be plugging it, I carelessly inserted a small screwdriver, dislodged the clog, and was greeted with an antifreeze geyser. I was fortunate it didn’t take my face off. Kids, don’t try this at home. But a surprising amount of air did come out. Unfortunately the bleeding it made no difference; the car still hovered around 2/3, a skosh higher if I pushed it. Which is to say that it ran like every Bavaria ever made, even when they were new.

I DID need to baby it on the drive down. That’s me and my friend Tom Samuelson. Photo by Ethan Siegel.

After the hot running and the lack of a/c, my other major complaint from the drive was the seats. Period-correct German seats are a thing of beauty, but the springs and 42-year-old horsehair are a recipe for discomfort. I have Recaros in my E9 and my tii, but putting them in the Bavaria would break up the harmony of the original interior. I took a Tempur-Pedic back pillow with me for lumbar support, but by the time I arrived at The Vintage, I was sitting on it to keep the springs from injuring my butt. Next time, a back and a butt pillow.

The Bavaria attracted quite a bit of attention at The Vintage. Even friends who’d heard the general outlines of the purchase were stunned by its condition. There were about half a dozen E3s there, including a professionally-restored one that was a rolling advert for the shop who did the work, but mine was the cleanest survivor car.

The Bavaria at home in the parking lot of the Hawthorne Inn. Photo by Ethan Siegel.

Perhaps it was the car’s vibe that attracted the guy in the chicken suit in the hotel parking lot. From the photos, it looked like Bavaria Lust. I have no other explanation, and those who witnessed the assault have remained strangely quiet about the incident. I guess you had to be there. Seriously. And I was sound asleep at the time.

My friend Paul Wegweiser DID put the license plate on the car, but to this day he swears he knows nothing about the guy in the chicken suit.

Yeah, it apparently got weird.

[The next day, I was greeted by the now-legendary Great Bavaria Feathering Incident, which was the handiwork of Paul Wegweiser, and which lives on to this day here on YouTube.]

The air temperature on the drive home was cooler, so I could keep my foot planted up hills without exceeding the 2/3 mark on the temperature gauge.

With Birgit home, I’ve ordered a triple-core radiator to address the hot running issues, and begun the process of upgrading the a/c. There’s a certain relief that the car doesn’t in fact have 49,000 miles on it; I’d feel honor-bound to maintain a high level of originality right down to the red cloth-braided a/c hoses and the lousy York compressor. With 149,000 miles, I can go for functionality with a clear conscience. And I’ve returned the aluminum center grille to the E9. Wouldn’t want to make the queen of the roost jealous.

I have absolutely no doubt that, if I stumbled upon a rust-free split-windowed ‘Vette or an E-type for $xxxx, I would be so insufferable that my car guy friends would vie for the right to beat me to death with a timing light. But that’s just not going to happen. Buying the rust-free easy-sorting Bavaria and successfully driving it 1600 miles to and from The Vintage was the perfect storm of timing, underappreciated classic, hard work, and dumb luck that makes hope spring eternal and keeps folks like us hitting Craigslist like one of those old ladies at the slots in the casino at 4am.

But, honestly, I’m out of money and out of space. I promise. This has got to be my last car.

Meant no car guy ever.

—Rob Siegel

[Stumbling upon this eleven-year-old unpublished article article was a surprise. Next week, I’ll write about the preparation and sale of the car. The juxtaposition of my “promise” above with the fact that the main reason I’m selling the Bavaria is because the car count has crept up to the unsupportable number of 14 is both bittersweet and funny as hell.]

____________________________________

Rob’s newest book, The Best of The Hack Mechanic, is available here on Amazon, as are his seven other books. Signed copies can be ordered directly from Rob here.