The BBC has been a reliable source of information for as long as I can remember, so when I noted a reference to one of my favorite roads, I fired up my trusty pre-Pentium 286 to check it out, and found a breathtaking article, “Driving Canada’s toughest road,” by travel writer Anna Kaminski. She is talking about the Dempster Highway.

Oh, Anna, Anna, Anna. No, it’s not all that tough. The Dempster is tame. If you want real driving adventure, especially in winter, drive the Telegraph Creek Road in British Columbia. That dead-end tightrope runs from Dease Lake on the Cassiar out 70 miles to Telegraph Creek, up and down along a ridge between the Tanzilla and Stikine Rivers; it features switchback 20% grades that will give you pause even in the summer.

By comparison, the Dempster is a modern—albeit unpaved—road, completed in 1979. It runs north from the Klondike Highway in the Yukon Territory to Inuvik in the Northwest Territories, a couple of hundred miles north of the Arctic Circle, so it’s probably an appropriate topic for the depths of winter. To quote Ms. Kaminski, “The Dempster Highway… traced a decades-old dog-sled patrol route. Now a new stretch of highway… extends a further 147 kilometers beyond Inuvik, all the way to the tiny settlement of Tuktoyaktuk on the shores of the Arctic Ocean.”

The Dempster Highway crosses the Arctic Circle.

Well, yeah—true as far as it goes. But let’s talk about that dog-sled route, which ran between the gold-rush town of Dawson on the Yukon River over what you might call rough country to Fort McPherson. The Royal Northwest Mounted Police ran patrols over this route in the early 1900s, but those 350-mile treks usually ran from Dawson. In 1910, Inspector Francis J. Fitzgerald tried to lead a four-man, fifteen-dog team back from Fort McPherson.

Mistake.

The Dempster is named after the RCMP’s William “Jack” Dempster, the corporal who led a subsequent expedition to discover the fate of the unfortunate four, who gained posthumous fame as Canada’s Lost Patrol. Their tragic destiny, related in Dick North’s book on that ill-planned venture, remains a stark lesson to those who wander the northland: Carelessness can kill you.

Anna Kaminski continues, “This long, lonely Dempster Highway is one of Canada’s ultimate road trips; an exhilarating four-wheeled adventure across a pristine northern landscape.” She is absolutely correct, but four-wheel drive is not strictly necessary. Indeed, in my decades of rallying the roads of the Great White North, it was mostly at the wheel of front-drive Saabs—but only until I could finagle the creative financing of a BMW 325iX.

You don’t need all-wheel drive to rally in winter, but it helps.

Ms. Kaminski does offer a few cautions to the modern traveler: “It’s also a hard drive in a hard land… as the road is unpaved, there’s no phone signal, and there’s only one petrol station around halfway along. Anyone who drives it needs to be prepared for misadventure, as I found out myself.”

Um, well, now: her car alerted her that a tire was losing air. “I had a jack and wrench and could change a tyre, in theory. But in the end, I managed to coast the last few kilometers into Eagle Plains on a near-flat, straight into the care of the resident mechanics, who patched my car up, enabling me to reach Inuvik the same day.”

Oooh, a near-flat! Heaven forfend!

I probably should not scoff at someone else’s intimidation. It’s just that to anybody who has lived in the frozen north, anyone who has driven there in winter, or especially anyone who has rallied on northern roads, the notion that we could die out here sort of comes with the territory. I mean, it’s cold. If I remember the book, when the original Lost Patrol went missing, floundering around in drifted snow while searching for the trail, the temperatures averaged 60 below zero for days on end. (Household hint: A proper antifreeze mix is from 50% to 75% antifreeze mixed with distilled water. Pure antifreeze at -60ºF turns into something resembling rubber cement. No, I was not foolish enough to run pure antifreeze; yes, I saw the gooey results when two flatlander rallyists tried it.)

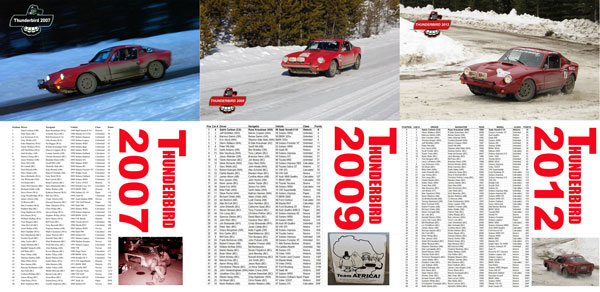

You can see why, when I set up a marathon rally that crossed the Dempster Highway, I named it the Rally of the Lost Patrol.

Highway crews in the Yukon and Northwest Territories carry on a kind of an informal competition, I think, seeing who can groom their sections of the road to the greatest perfection—which can be deceptive. The smooth, white snowpacked surface, generally free of traffic, can lull the senses. I was on cruise control on the Dempster in the early ’90s—cruise control, really!—measuring distances for the rally, when I noticed a herd of caribou off to my right. They weren’t exactly stampeding, but they were definitely maintaining a good trot, and heading straight for the highway. Now, this was in the Bad Dog, my BMW 325iX, with all-wheel drive on Michelin Alpins, so I was already at a pretty substantial rate of knots when I saw the caribou, so I knew that stopping was out of the question; my only hope was to floor the Bad Dog and hope that I reached their crossing point before they did. Of course, a stock 325iX has 167 anemic horsepower, and about enough torque to wind up a rubber band, so it’s not like I suddenly shot down the road, accelerating from Already Too Fast to Stupid; I just kept my foot on the floor and eased as far to the left as I could while umpteen thousand caribou hoofed it toward a collision and my speed oozed its way higher and higher.

Just so you know: Caribou herds can range from 20,000 to more than 300,000 animals. You really do not want to hit even one.

And I didn’t—but it was close: The leaders of the herd were indeed scrambling up the bank onto the roadway as I flew by. Mercifully, all I could see in the mirrors was the opaque white cloud of snow kicked up by my passing.

The Bad Dog was the perfect choice for playing in the Arctic.

I had several other adventures on that trip, mostly benign, including being run off the road (not the Dempster, but the Campbell Highway north of Watson Lake) by a careless Yukon DOT truck—which taught me the importance of quality. The Bad Dog and I were uninjured, but our misadventure deflated a tire. No problem, I thought, because like Anna Kaminski, “I had a jack and wrench and could change a tyre, in theory.” Fortunately, the DOT guy hung around after apologetically pulling me back up onto the road, because when I applied my eighteen-inch breaker bar and Chinese impact socket to the wheel bolt, the socket shattered in the cold like a crystal Champagne flute. The loan of a 17-millimeter DOT socket got me on my way, and when I reach Watson Lake I chased down a Snap-On truck driver and demanded that he sell me a 17-millimeter deep impact socket, price no object.

I still have that Snap-On socket. I kept the fragments of the shattered one, too, as a reminder.

The problem with learning things the hard way is that sometimes you have just one chance to get it right. I still have no idea how I survived the Great Moose Slalom on the Cassiar one night. In the dead of winter, snow had been piling up for months, the walls on the sides of the road growing higher and harder as the plowing crews came through. I entered one of these frozen canyons at about two in the morning, only to find a startled moose dead ahead of my high beams. Again, there was no way to stop, so the only option was to zig left and hope the moose stayed where he was, and then zag back into some sort of control before hitting the ice wall on my left. But just as I got the Bad Dog straight, I realized that I was heading for another moose, this one preferring the left lane, so yank the wheel again, this time a quick right-left, stay there stay there stay there and hooray! Another moose-cone dodged.

I suppose that the lesson I learned from that one was to never stop driving the car. It seems that I go to the brakes only as a last resort, instinctively preferring to drive myself out of trouble. Sometimes it works.

The Dempster taught me another great lesson, which I tried to pass on to drivers in the Rally of the Lost Patrol. I told them of the blinding whiteouts that can occur when the wind creates a horizontal blizzard in the White Mountains. “There are times when I couldn’t see the front of my hood,” I said, but I could tell that they weren’t really listening. They had no fear; they were rallyists. They were men—the kind that laugh at danger.

Proper attire is a key to Arctic survival.

That rally began in Seattle. Several days later, we were on the Dempster Highway, and I drove ahead to set up a timing control—in the White Mountains section. There I sat, and waited… and waited. The rallyists were late, all of them. I began to worry.

Finally the cars arrived, all in a flock, and their drivers had gained a new respect for the harsh realities of nature. The wind had indeed picked up, created a whiteout so severe that the cars had to slow to a walking pace—each car following the one in front at a distance of about two feet, and the lead car following a man on foot. He was wearing a bright red parka, the only visible object in a sea of milk.

Visibility is sometimes iffy.

Anna Kaminski’s adventures did not end with her near-flat tyre. “Just as I passed the Dempster-Klondike junction, I got a strong whiff of petrol,” she writes. “I watched in disbelief as my fuel tank emptied within seconds, and the car came to a halt as the engine died—yet another reminder of the obstacles that the Dempster may throw at you. There was no phone signal, and as I stood on the Klondike Highway some 40 kilometers east of Dawson City, my car abandoned, it was possible that potential rescuers would not drive by for hours. However, within minutes of my breaking down, a Good Samaritan picked me up. As he drove me to my guesthouse in Dawson City, I realized that this had been part of the Dempster’s charm all along: that whenever I’d come close to disaster, fortune smiled on me.”

You know, Anna, I could probably say the same thing—unlike the members of the Lost Patrol. They had no luck at all.—Satch Carlson