Last week I wrote about Sharkie, my 1979 Euro 635CSi, which blew a heater hose on the way to the Vintage in Asheville. (And yes, the event itself was fabulous; look for my upcoming Roundel magazine piece on it.) There was, however, one other thing that went wrong on the trip, but it was minor: As I was returning from the Z-car exhibit at the BMW CCA Foundation, and heading back on I-26 over the mountains into Asheville, Sharkie’s a/c, which had worked splendidly on the drive down, suddenly died.

As you probably know, I’ve made something of a career (a very low-paying career) out of having functional a/c in my vintage BMWs. Sharkie was the most involved of the bunch, as the car didn’t have a/c when I bought it, and as the a/c wiring on a ’79 E24 is more involved than on a 2002-era car. I found someone who was parting out the same car—an early Euro E12-based E24 with air—who sold me all of the a/c components. As I’ve written in my book Just Needs a Recharge: The Hack Mechanic Guide to Vintage Air Conditioning, what you need most for an a/c retrofit is the stuff in the cabin (meaning the evaporator assembly, the console, and any switches, wiring, and ductwork); everything under the hood—the condenser, fan, compressor, and bracket—you’re almost certain to replace with newer, better components to make things work as well as possible with R134a refrigerant.

I did all this with Sharkie, and the a/c had worked fine for several years—until last Friday, heading up that hill. In the heat and rain.

If the a/c had gradually grown warmer, the diagnosis would’ve been that the refrigerant had slowly leaked out, and there might have been the possibility that I could’ve stopped at an AutoZone, grabbed a few cans of R134a, and recharged it. (The title of my book is a joke—it never “just needs a recharge”—but sometimes leaks are so small and slow that you can get a few weeks of cold out of it before putting the patient on the table for surgery.) But because the failure seemed to happen suddenly, the odds of success of that approach were small. The only real hope for an easy field repair was if the compressor wasn’t being switched on. Of course, if the problem was in the climate-control wiring or relays, it would be a pain to fix, but in the short term I could simply wire the compressor directly to the battery.

Unfortunately, I watched the hub on the compressor’s nose go from freewheeling to engaged when a friend clicked the switch on, so that wasn’t it.

Sharkie’s console looks almost the same as it did before the a/c retrofit, but there are additional wiring and relays behind that climate-control panel so that when you turn the temperature knob to the cold region, it clicks on the a/c. The non-a/c (left) and a/c versions of that climate-control panel are shown here. You can see the temperature switch and sensor and the relays bulging behind the one on the right.

So alas, I, the yankee with the odd preoccupation with air conditioning, had to drive my shark a thousand miles home with no a/c. Oh, the pain, the pain!

Really, it was fine. It was a much cooler drive back than it was down. Other than about ten hot minutes in traffic, I was perfectly comfortable doing the “R75/2 refrigerant” thing (75 mph, two windows down). But when I got home, I did want to diagnose and fix it.

I hooked up the manifold gauge set, which is a pain because I never spliced R134a-style snap-on charging ports into the hoses; instead, I am still using the small screw-on R12-style service ports on the back of the compressor to connect the manifold gauges. So I had to either remove the air-flow meter and air-filter box (they’re on the same bracket) to get at the ports from the top, or jack up the car and crawl under it.

I did the latter.

With the gauges connected, it revealed zero pressure. I was correct: All the refrigerant had leaked out. But from where?

The hoses are screwed onto the not-exactly-convenient R12-style charging ports on the back of the compressor.

I’ve written extensively, both in the book and in these online pieces, about my use of nitrogen to leak-test an a/c system. I really don’t understand why it’s not a more widely used technique. Instead, shops either pull a vacuum (which will reveal a leak but not easily pinpoint it), or they recharge with dye and then look for where it leaks out. Pressurizing with nitrogen lets you find big leaks in seconds by simply following your ears and then using your hands, literally laying them on the components in the area where you hear the leak and feeling the nitrogen rushing out. If the leak is small enough that you can’t hear or feel it, you spray with soap solution like Big Blu and look for the bubbles.

My nitrogen tank and manifold-gauge set are aces at leak detection.

Now, when you do this in a vintage BMW like a 2002, a 3.0CS, a Bavaria, a 320i, an E12 5 series, an E12-based shark like mine, or an E28—all of which have a Behr evaporator assembly that’s riveted shut and has the evap core, expansion valve, and fan inside—you pray that you hear the hissing coming from under the hood, because if it’s coming from inside the console, you’re in for several very unhappy evenings, since the console and the evaporator assembly have to come out and then the assembly has to be taken apart to find the leak.

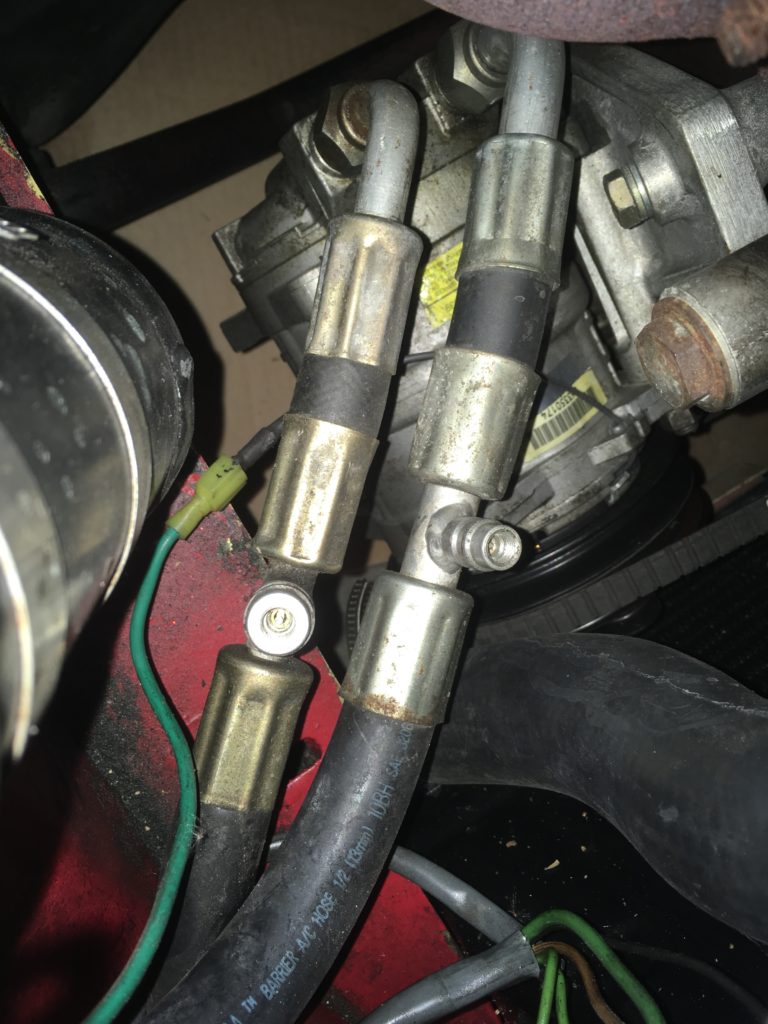

Fortunately, the hissing came from under the hood, and I quickly found that the fitting for the hose on the discharge side of the compressor had completely loosened, perhaps due to vibration from my having hammered on Sharkie for 2,054 miles. I tightened the fitting, pressurized the system to 100 psi, let it sit overnight, and verified the next morning that it hadn’t budged an iota. Done.

It was the nearer of these two fittings that was completely loose.

Well, maybe.

The system is tight, but the episode reminded me that relying on those R12-style ports on the back of the compressor really is a pain. In addition to the poor access, these screw-on fittings always discharge a fair amount of refrigerant when you unscrew the hoses from them, whereas the snap-on R134a fittings are as tight as a drum. Those really are better in every respect except their physical size, which is why you can’t simply use R134a adapters on the back of the compressor. If you do, you can fit one R134a charging hose, but not both.

One R12 charging fitting on the back of the compressor has an R134a adapter.

While the system is still empty of refrigerant, I think I’ll scope out installing the proper charging fittings in an easily accessible location. On my last a/c retrofit (the Clardy system into Louie, my ’72tii), I used compressor-hose fittings with charging ports integrated directly into them, but on the shark, there’s just not enough room.

My test-fitting of the charging-port-on-the-compressor-fitting in 2017: It barely clears the block. And that’s before you even put the charging hose on it.

On other cars, I’ve spliced the fittings into the compressor hoses, but on the shark, the air filter is right in the way.

R134a-style charge fittings are spliced into the hoses of my 3.0CSi.

Rather than do this in haste, I think I’ll look at it for a bit, figure out what’s best, and order what I need. And while I’m doing that, I can address the heater-core bypass issue I mentioned last week and install the kind of bypass valve I used in my E9 years ago.

After all, it’ll be a while before the next road trip in hot weather. A guy needs winter projects to look forward to.—Rob Siegel

Rob’s new book, The Best of The Hack Mechanic, is available here on Amazon, as are his seven other books. Signed copies can be ordered directly from Rob here.