Last week I dangled the possibility of moving the Bavaria along. Any action on selling it, however, rapidly got back-burnered, as I quickly encountered some things on the car that required significant lead times. Meanwhile, I had pressing issues with other cars.

The first Bav issue was that while driving it home from storage in Fitchburg, I noticed that the odometer wasn’t turning. I had no recollection whatsoever of the odometer having headed to the Great Odometer Graveyard in the Sky, and having driven the car to the Vintage in 2014 and 2015, and to Vintage at Saratoga in 2017, I would’ve thought I’d have noticed and remembered such a thing.

The Bav’s odometer was stuck at 52,103, almost certainly having rolled over once. (When I bought the car, because of its survivor vibe and its delicious interior, I entertained the possibility that the five-digit mileage was original, but an oil-change sticker I found inside the door jamb with mileage of 65,870 put that fantasy to rest.)

Seeing the odo stuck, I was curious what the mileage had been when I bought the car, so I pulled out the car’s folder and looked at my copy of the original bill of sale. It listed 49,390 miles. So according to the odometer, I’d put on 2,803 miles. Let’s see: The Vintage was still in Winston-Salem in those years, 760 miles each way… plus about 190 to Saratoga Springs… that’s a total of about 3,420 miles. So yeah, it looks like the odo bit the dust on the drive home from the second trip to Vintage, I somehow forgot about it, and there are at least 600 unrecorded miles.

I love how the Bavaria’s instrument cluster looks at home in any BMW from 1968 through the early 2000s.

So I dived into odometer repair.

Whether I wound up changing the gear myself or sent the speedometer out, I first had to remove it from the car. It occurred to me that I’d never done this on an E3 sedan before. When I did the odometer in my E9 coupe a few years ago, I was surprised that you left the cluster in place but pulled the speedometer out from the back. It sure seemed like the Bavaria’s whole cluster should tilt forward and slide out, as it does on most modern cars (and on a 2002), but after dropping the steering-column panels and fishing around behind the cluster, I couldn’t find any knurled nuts holding it in place. I knew that I had an ancient Haynes 2800/3.0 manual kicking around somewhere, but I couldn’t find it.

I poked around in the E3 section of e9coupe.com and found one reference to a set screw; to remove it, you first have to pull off “the grille.” The grille? What, you have to go in through the nose of the car?! Obviously I was missing something. But when I looked on top of the cowl covering the cluster, sure enough, there was a grille. I was astonished that I never noticed it before, and even more surprised when I pulled it off and found that under it was the original speaker for the car’s radio. You learn something new every day.

The grille. Definitely not in the nose.

A speaker. Ha! Who knew? The set screw holding in the cluster is in the foreground.

With that, and the steering wheel removed, and the speedo cable undone from the back, the cluster was tilted forward. I unplugged the connectors, and the cluster was out of the car in minutes.

Voilà!

I undid the four screws holding the speedometer to the cluster and was soon holding the errant gizmo in my hand.

Is this how heart surgeons feel?

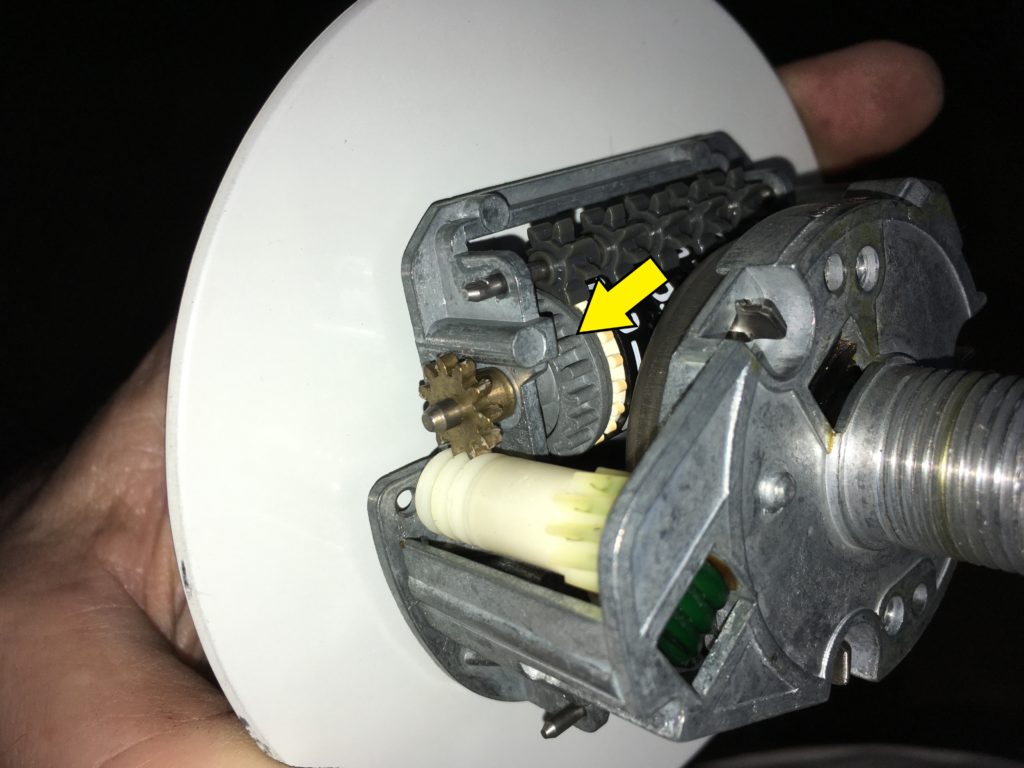

I’ve repaired quite a few odometers. How easy they are depends which gear is bad, and whether replacing it requires pulling the needle off the face of the odometer and withdrawing the guts. The only one on which I had to do this was the one in the E9 (my ’73 3.0CSi), and although I got it done, it was sufficiently harrowing that I’d rather pay a professional to do it as opposed to tangling with it again. The gears for the E3’s odometer weren’t click-and-buy on Odometer Gears’ website (odometergears.com), so I messaged owner Jeff Caplan. Shortly thereafter, he called me on the phone and talked me through which gear was easy and which was a pain.

The bad one on mine was the latter, of course, so age having imparted wisdom, I boxed the speedo up and sent it to Jeff. I had it back in about a week and reassembled the cluster. Thanks, Jeff!

This was the gear that was bad.

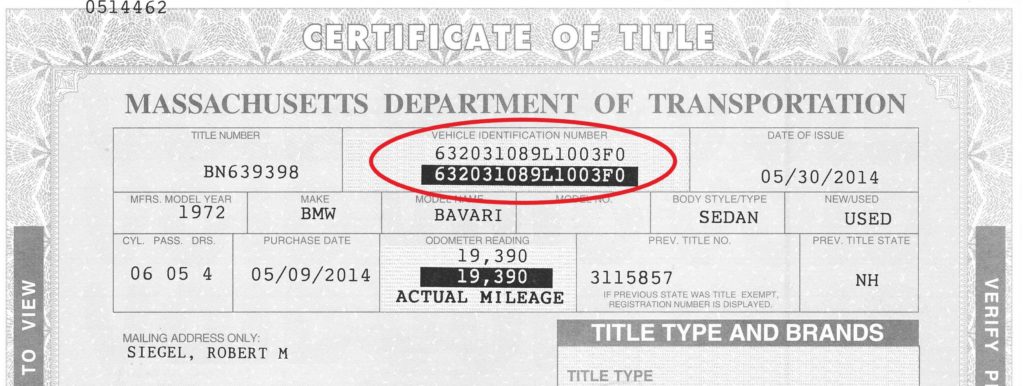

The other odd thing that put the brakes on any inkling of quickly writing up an ad for the car was that while I had the car’s folder out to look at the original bill of sale, I also looked at the title, and saw something I’d never noticed in the seven years I’ve owned the car: The VIN is completely wrong.

Like any other 1970s-era BMW, the Bavaria has a short seven-digit VIN (3103284). Instead, what was listed on the title appeared to be a modern post-1981 long seventeen-digit VIN, but if you count digits, it’s actually only sixteen. I checked the car’s registration, and found that the VIN is wrong there as well.

What? On a 1972 car?

But wait; there’s more. If you look beneath the VIN at the mileage, you’ll see that it reads not 49,390 miles, as it says on the bill of sale, but 19,390 miles. So clearly whoever entered my registration information into the registry computer that day got his or her wires crossed not once, not twice, but three times. Even if I’m not going to sell the car soon, obviously I should correct the title.

Unfortunately, even though the major slug of COVID-19 appears to be past and things are returning to normal, the Massachusetts Registry is still only processing things like requests for title changes through the mail. I downloaded the form, read the instructions, and found no instructions at all on correcting VIN errors. However, it does say that you need a notarized affidavit to change the mileage. The title of the form is “Amend/Lienholder Maintenance/Duplicate Title Application,” so really, it’s mostly for address changes, loan payoffs, and lost titles.

Then I remembered that decades ago, I had a VIN error on a title, and I recalled that there was a process that requires the car to be inspected by a police officer. The Amend Title form doesn’t refer to this; you just have to know it. I verified that the Bavaria’s four VIN stamps (on the engine-compartment sheet metal, the riveted VIN plate over the fender, the steering-column cover, and the engine block) all matched, downloaded the “Proof of Visual Inspection” form, then drove the car the mile to the West Newton police station.

The officer wasn’t at all familiar with German cars, and was initially suspicious that there wasn’t a VIN tag on the door jamb, but when I mentioned the long/short VIN thing, he nodded, said he recalled the issue on an old Nova he once owned, examined the Bavaria’s VIN tags, and signed off on the form. I then sent all the paperwork (including, as required, the original title, which gave me the heebie-jeebies) to the Massachusetts Registry of Motor Vehicles.

I was planning to put the Bavaria up on the mid-rise lift and photograph the undercarriage while I wait for a corrected title, but temperatures in Boston crept over 90 degrees and I made a snap decision to begin a long-desired a/c retrofit to my ’72 200tii, Louie—so not only did the Bav not get the prime spot on the lift, it’s currently boxed into the corner of the garage by an explosion of air-conditioning parts.

And then my E39 530i—ostensibly my daily driver, except that I don’t really daily-drive anywhere, at least not in the commuting sense—died.

And then I began the annual early summer ritual of resurrecting our little VW Eurovan-based Winnebago Rialta RV so that Maire Anne and I can go to the beach.

As far as the Bavaria goes, none of this is a bad thing. But at least when I drive it again, the odometer will work correctly. And it can be at peace knowing that it has a stately, mature, and proper seven-digit VIN, instead of unintentionally committing automotive identify fraud as some young post-1982 whippersnapper.—Rob Siegel

Rob’s new book, The Best of The Hack Mechanic, is available here on Amazon, as are his seven other books. Signed copies can be ordered directly from Rob here.