I haven’t driven my 1973 3.0CSi much during the past few years. It hasn’t seen a multi-day, multi-state road trip since the Great Drenching Event of 2013, when on the way to the Vintage in Winston-Salem I hit about 500 miles of torrential, unrelenting rain that so completely soaked the rust-prone car that I felt like I’d blown the car’s entire lifetime moisture allocation in a single day. It made me determine that unless I can see a completely clear weather forecast, I don’t want to risk the exposure—and really, you never can have an absolutely guaranteed five days of moisture-free driving on the East Coast. Since then, I’ve used the car around town and for a couple of quick overnights, but nothing more.

The sun finally came out after the Great Drenching Event of 2013.

In addition, when I have driven the car, there have been two vexing electrical issues. The first was what seemed like a hot-start problem. Sometimes, after driving the car, I’d turn the key and either hear a click and then nothing, or a faint click, or no click. I didn’t think of this as a big deal; I just needed to catch it in the act and put the time into diagnosing it.

But the other issue was a bit more troubling: The car developed an intermittent stumble. I’d be driving it, and it would momentarily lose power, then recover. It would happen quickly enough that I couldn’t watch the tachometer and see if it dropped to zero. On a vintage car, this is the classic way to tell if it’s ignition (the tach is connected to the ground side of the coil, so if the coil stops firing, the tach will drop) or fuel delivery. This car is a CSi, so it originally had Bosch D-Jetronic injection, but it had been removed before I bought the car and replaced by dual Webers. I drove it that way for fifteen years, then retrofitted Bosch L-Jetronic into it. It’s also still running on its original electric fuel pump, which had never been removed, so the stumble could be due to a number of things.

This spring, when I unpacked my garage from its winter sardine-like configuration—in which four cars are shoehorned in, with one on wheel dollies—one of the cars needed to go somewhere to keep it out of the elements, so I shuttled the coupe off to a space I sometimes use in a warehouse associated with my former engineering job. I still consult to them and keep their work truck inspected and registered, so in a quid pro quo, I sometimes stick a car in the warehouse for a few weeks or months. Because I wasn’t doing a swap of one car for another, I had Maire Anne follow me the fifteen miles up to Woburn so that she could give me a ride back.

Shortly after I pulled onto I-95, the E9 completely lost power and died. As was the case when it had stumbled, it happened so quickly that I didn’t see what the tach did. I pulled into the breakdown lane, checked that the battery connections were solid, and looked for pulled-off wires, but found none. I twisted the key and the car started immediately. I drove the ten miles up to the warehouse, but having fixed nothing, I was waiting for it to die again. Fortunately, it didn’t.

My wife documented my misfortune.

The car sat in the warehouse for a about a month. I retrieved it in July, swapping it for the Lotus Europa. I gingerly drove the coupe home, hugging the breakdown lane.

It ran perfectly fine.

A few weeks later, on my birthday, Maire Anne, Ethan, and I drove up to Essex, Massachusetts, to eat fried clams. I threw caution to the winds and took the E9. It was fine, and we had a perfectly glorious summer drive in it.

But I kept expecting the other shoe to drop. A week later, it did—and in my own driveway, when I was shuffling the cars around.

The E9 was in the front-most spot in the garage. I pulled it out to get to one of the other cars and parked it in the driveway. When I went to move it back into the garage, I twisted the key, and not only did the starter go CLICK and then stop, but I also noticed that the dashboard lights went out. “Good!” I thought. Complete failure, and in the most convenient location possible. What more could you ask for?

No-crank problems on vintage cars are almost always straightforward. If the battery is fully charged and verified as good with a battery tester, and you turn the key and hear a click and then nothing, but the dashboard lights stay lit, either the starter is bad or there’s enough corrosion on the battery-cable terminals and/or battery posts that the dashboard lights can draw their comparatively low amount of current, but the starter can’t draw its 100-or-so amps. Sometimes simply smacking the battery cable terminals with a block of wood is enough to re-seat them, break the corrosion, and get the car to start.

If you turn the key and hear nothing at all, either the spade connector has come off the terminal to the starter solenoid, the wire has broken off the connector, there’s a break in the wire leading to the back of the ignition switch, or the ignition switch itself has failed. Connecting a remote start switch from the solenoid directly to the battery is the best way to narrow it down; if you do this and the starter spins, then the problem is in the connection to the ignition switch. If it still goes click or you hear nothing, then the starter or solenoid is usually bad.

But with the E9’s dashboard lights going completely out when I tried to crank the starter, the problem could only be an intermittent electrical connection, on either the positive or negative side, to everything in the car.

I undid both battery connectors from their posts and cleaned and re-seated them. No change.

I unbolted the end of the negative cable from the block and cleaned it with a file. I did the same with the end of the positive cable that went to the starter. No change. So where was the problem?

Then I looked and saw something I’d repressed like a bad memory. I knew it was there, but never wanted to deal with it.

Every car has at least two connections to the positive battery terminal. The thick one is the high-amperage cable that leads directly to the starter motor (or, rather, to its solenoid); the second, thinner cable powers everything else on the car. This one usually splits off three different ways, going to the charging input from the alternator, the fusebox, and other unfused connections on the car. In addition, on vintage cars that have had electrical augmentations for aftermarket things like power amplifiers and big relay-operated radiator and condenser fans, those things are typically attached directly to the bolt on the positive battery terminal with a ring connector and given their own in-line fuses.

When I bought my E9 34 years ago, it had already been subjected to some creative electrical splicing. There was a bundle of wires, including a thick wire that was connected to the positive battery terminal with a ring connector, leading into a cylindrically-shaped mass of electrical tape. The offending mass hung down to the right of the battery, just out of sight. I remember squeezing it, feeling that it was hard and uniform inside, assuming that it was some sort of a barrel connector, and deciding to leave it alone.

And leave it alone I did—until now.

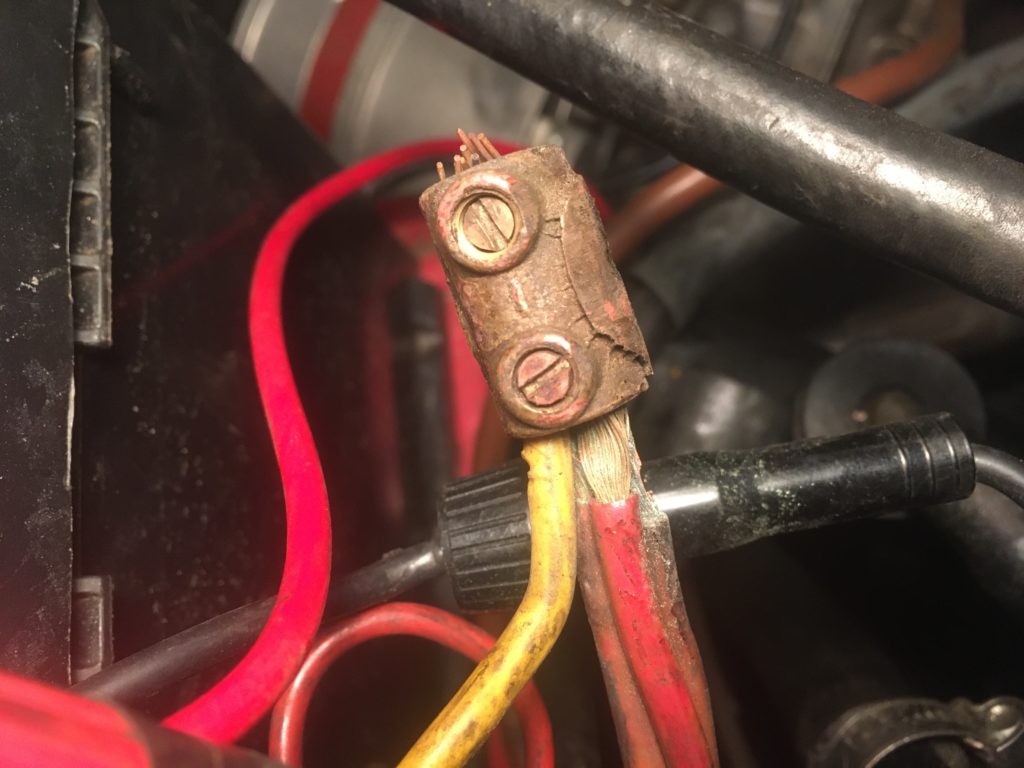

I disconnected the negative battery cable so that I wouldn’t short anything out, peeled back the electrical tape, exposed a brass barrel connector—or what had once been a brass barrel connector— and tugged on the wires.

One of them slid right out. Gotcha!

Yeesh. The car’s entire electrical system was running off this.

Now, when you find something like this, there’s a question of how to deal with it. It had to be fixed and made functional and safe, but how much improvement should I try to effect? Should I also try to make it less cringe-worthy? I decided that since the car was now sitting not in the garage but out in the driveway, the immediate goal had to be to get it back together and make the car driveable, and if I had to revisit the repair again at some point, that was fine with me.

The wires wouldn’t reach all the way to the battery, so some sort of splicing connector was needed. I rooted around in my electrical box, but didn’t find another connector even close to being large enough to join that many wires together. I puzzled it over for a bit and decided to simply re-use that brass barrel connector. I cleaned the inside with a wire brush, cut the lightly-corroded ends off all the wires, stripped them of a bit of insulation to expose fresh copper, and rolled the ends tight with my fingers. I considered coating the ends with solder, but thought that this was best left for a more permanent repair in the future.

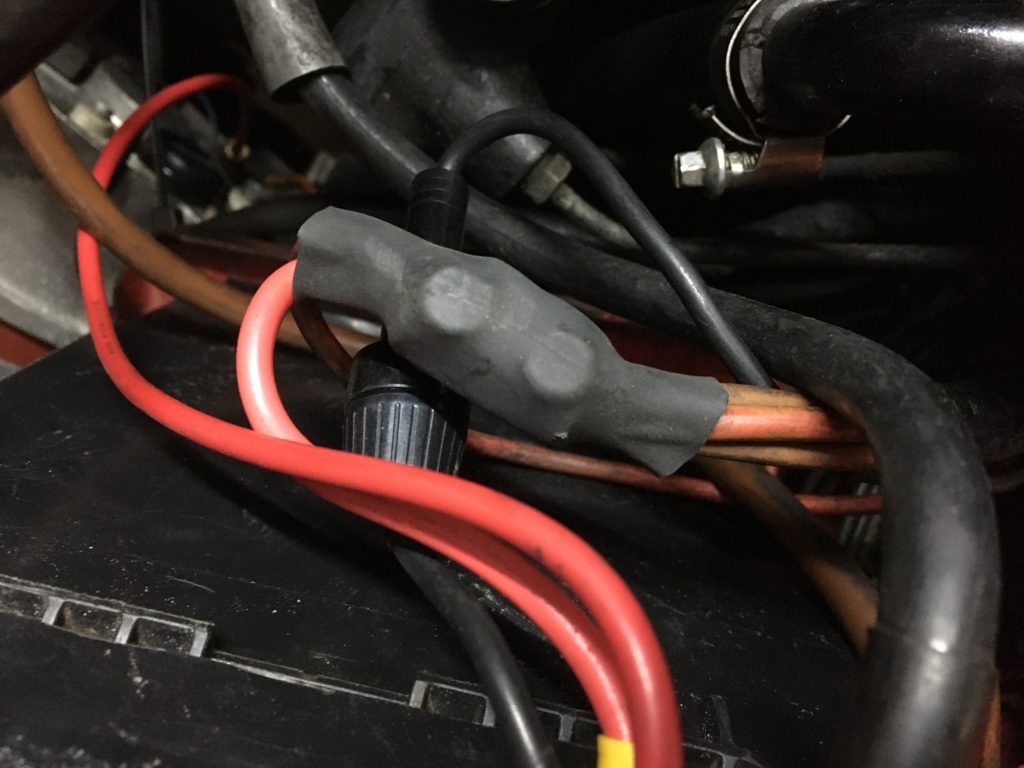

I packed the wires back into the brass barrel connector, tightened the screws back down, and gave the wires a hard tug. Nothing pulled out. Then I slid on a piece of heat-shrink tubing and shrank it down with a heat gun.

Much better.

At some point I’d like to neaten up the engine compartment a bit, and as part of that project, I may revisit this electrical kluge. But for now, I completely solved the mystery, it’s fixed, it’s safe, and it enables me to drive my favorite car without the nagging feeling that the boogie man is going to jump out of the closet and drag the car back into the breakdown lane.

I do love this car.Of course, this means that I should drive it somewhere farther than just to Essex for clams.—Rob Siegel

___________________________

Rob’s most recent book, Resurrecting Bertha: Buying Back Our Wedding Car After 26 Years In Storage, is available here. on Amazon. His other books, including Just Needs a Recharge: The Hack MechanicTM Guide to Vintage Air Conditioning, are available here on Amazon. Or you can order personally inscribed copies of all of his books through Rob’s website: www.robsiegel.com. His new book, The Lotus Chronicles, will be available in September.