My last three pieces were about purchasing and towing home a 48,000-mile original-owner 1973 2002 that had been sitting for a decade in a barn in Bridgehampton. With the car (“Hampton”) safely in my garage, the sort-out process began.

On vintage cars, we all say that the condition of the body is paramount and mechanical condition is secondary, and that’s true, but at some point in the purchase process, you need to assess a car’s mechanical condition, or if you can’t assess it, at least somehow factor it into the car’s value to you. Cars that sit for ten years typically develop significant mechanical issues which make the importance of whether or not they “ran when parked” diminish with time. Fuel turns to varnish. Brake and clutch seals dissolve into the hydraulic fluid. Brake shoes and pads stick to drums and rotors. Oil seals harden and leak. The clutch sticks to the flywheel. Pistons and rings stick to each other and to the cylinder walls. Sometimes they unstick with use, and sometimes they don’t, and the car ceaselessly spews clouds of oil until the engine is rebuilt. The exhaust turns to Swiss cheese. Important rubber under the car such as the giubo, center support bearing, and bushings harden and crack or turn to goo. Indoor storage at non-Death Valley temperatures helps, but it certainly doesn’t prevent all issues.

Those are just the expected problems. There are also the unknowns. Why was the car parked and stored in the first place? Often it’s because something big and bad happened. If you can’t drive a car, you don’t know if the head is cracked or if the transmission synchros munch or if the rear end rumbles.

And then there’s the myriad of minor but annoying sort-out issues. If the blower fan seized from sitting (and they often do), replacing isn’t expensive, but it’s a pain in the butt. Suspension, steering, and on down the list.

It’s impossible to know how much of this is going to be the case on a particular dead car. If you simply assume the best case (that the car needs nothing), you’re a sap and will doubtlessly get kicked in the teeth by the financial vagaries of vintage car resurrection. But if you always assume the worst case, someone would need to give you the car for the numbers to make sense, and that almost never happens, so you’d never buy and resurrect anything. If you keep your wits about you and pay short money for a dead car because you’d walk away above a certain price, and the resurrection and sort-out are easy, then you do the happy dance. But if you pay too much and find the car needs literally everything, it makes you rue the day you let your lust get the better of you.

When you start doing this as a young person, you let youth’s passion rule and forget the lessons quickly and make the same mistakes over and over again. But after 30 years, some of it sinks in, and you either walk away or you don’t, and if you don’t, a number just floats into your head that is engineered to be a low but not completely unreasonable offer. What’s more, the number feels about right. Add in the wisdom that it’s not worth losing a car you’re interested in over the last five hundred bucks. With luck, you do this over the course of a few cars, and maybe you get the benefit of dollar cost averaging.

There. You now know everything I know.

The new kid gets to sit with the prom queen.

This was essentially the process I went through when agreeing on a price for Hampton with the seller. The car did appear to be in very good, original, virtually rust-free condition, but I paid a fair chunk of change for it, enough that if it turned out to have a cracked head and munched second gear and needed a clutch and all the brake and clutch hydraulics needed to replaced, I would not be happy. I did get the car running in the barn in Bridgehampton prior to purchase which ameliorated some risk, but, although I didn’t see clouds of oil smoke, all I did was run it for five seconds, shut it off, get the clutch working, restart it, move it a foot back and forth, and shut it off again—worth something, but hardly a thorough risk-eliminating evaluation. Even in going from the barn to the trailer, found that I had to wire in an electric fuel pump and trim off a fuel hose to eliminate a split that was spurting gas.

So, realist that I am, I was expecting to find that significant sort-out work was going to be required to begin driving the car. I already knew that all of the brake fluid had leaked out of the reservoir, and clearly it went somewhere. And coolant streamed out when I rotated the engine, I assumed from a bad water pump. The number of problems certainly wouldn’t be fewer than that, only more.

And then there’s the fact that the character of this car was different than anything else I’d ever bought. Owning a 48,000-mile car is a fundamental adjustment for me. I feel honor-bound to try and maintain the car’s originality, and that’s just weird. This car has a Weber and the accompanying little rectangular K&N air filter, but it also still has the brackets and cold air feed for the big round vinyl album-sized factory air cleaner. Normally I’d remove those remnants, but instead, my first purchase for the car was an original Purolator air filter housing. Similarly, it still has the EGR lines and the charcoal canister connected. Under any other circumstances, I’d rip them out in short order, but with Hampton, I just can’t.

The Weber and rectangular K&N filter and original air cleaner bracket (center), air box (black, right), EGR lines (silver, behind the air box) and charcoal filter (bottom right).

Utterly coincidentally, Hampton’s purchase occurred just after I’d made the decision to sell Kugel, my identical-looking ’72 2002tii. Why? The usual issues of money and space. I certainly didn’t set out to sell one Chamonix / Navy 2002 and replace it with another. The weekend after I returned with Hampton, I floated Kugel for sale on Facebook, and it was quickly purchased by Jim and Susan Strickland who’d bought my E28 (“the Lama”) last winter. I’ll be delivering Kugel to the Stricklands at Oktoberfest a few days after you read this. So, for a very short period of time, I have two beautiful Chamonix / Navy 02s in my garage. Occasionally, my 94-year-old neighbor is sitting on her front porch when I pull one of the cars out of my garage, park it in the driveway, throw a cover on it, then pull the other car out. I wonder if she goes inside and checks her meds.

Fill my eyes with that double vision…

Although I had a fair amount of prep work to do with Kugel for the sale (and a little for the drive), I couldn’t resist starting to sort out Hampton. I’d changed the oil and filter in Bridgehampton prior to starting it, so my first task at home was valve adjustment. This was a joy, as I love adjusting valves. And, on a newly-purchased car, it’s an intimate act, like adopting a mangy dog and giving him his first bath. The head was varnished, but nothing looked alarming.

Varnished, as expected.

The empty brake fluid reservoir turned out to be due to the reservoir’s three hoses being porous (it was pretty obvious when the fluid I’d poured in in Bridgehampton was nearly gone and the hoses themselves were wet). I replaced them.

All three of these hoses had become porous.

Next was the fuel delivery system. In Bridgehampton, I’d pulled the top off the Weber and found it clean as a whistle, and had gotten the car running by first filling the float bowl manually, then running the Weber off an electric fuel pump with a hose in a gas can, but the car had such trouble idling that I almost couldn’t load it on the trailer. Mysteriously, once I had it home, the won’t-idle problem never recurred. Maybe a plugged passageway or jet inside the Weber cleared itself. I found that the car ran fine off its mechanical fuel pump. I removed the fuel level sensor and peered inside the gas tank, didn’t see anything scary in terms of rust or sediment, used the electric fuel pump to suck the old gas out, and poured five gallons of fresh gas in from a can. Fuel-wise, Hampton appeared to be happy.

At that point, I was prepared to take the car for an inaugural spin around the block. I pulled it to the top of the driveway and let it warm up, then saw a significant amount of antifreeze streaming from the nose. Oh, right; forgot all about the water pump that was leaking in the barn.

This was a non-trivial amount of coolant.

I pulled it back into the garage and was about to tear into the cooling system when I paused and decided to eyeball the source of the leak to be certain. To my surprise, I found no coolant coming from the water pump or anything near it, and what I saw in the driveway appeared to simply be overflow from under the cap. Over the next two days I warmed the car up several times, and did not find any coolant at all. However, I have zero question that, when the car was in the barn, it leaked antifreeze when I rotated the engine by the fan blades to check if it was seized, and did it again as soon as I started it up, so this is also a bit of a mystery. It could be that, now that the water pump has spun, it’s sealing better, but that’s just a guess. On one hand, prior to any sort of a road trip, I’d be a fool not to pull every hose and scrape the corrosion off the coolant necks, and probably replace the water pump while I’m in there, but I wanted to see how the car drove and get a sense for what else it needed before laying it up.

With that, Hampton gingerly set foot on the asphalt of West Newton, its first drive on a road since 2008. First impressions were that its bone-stock suspension felt floaty and boaty compared to Kugel’s Bilstein / Suspension Techniques package, but there was no banging or thunking, and it drove quietly and shifted smoothly. But then, at almost exactly 20 mph, a loud vibration set up under the transmission tunnel. It was the textbook symptom of a bad giubo.

I pulled the car onto the mid-rise lift. I was certain that I’d find the giubo fractured into pieces, but surprisingly, it looked fine. I disconnected the front of the driveshaft to examine things more closely, as sometimes a giubo will look okay until you remove it, and then you’ll see cracks around the metal sleeves that go through it, or find a cracked ear on the transmission or driveshaft flange or an elongated hole in which a bolt is wobbling around. Nope, all that looked perfectly fine. Even the center support bearing looked okay, a far cry from my last two resurrections (Bertha the ’75 2002 and Louie the ’72 tii) where the bearing was completely detached from the surrounding rubber.

But when I wiggled the CSB, I found that there was some play in the bearing. More than that, the rubber around it appeared to have taken an off-center “set” from the decade of inactivity. Figuring that the driveshaft vibration must be due to the CSB or the shaft itself being badly out of balance, I unbolted the driveshaft from the differential, pulled it out, and set about changing the CSB.

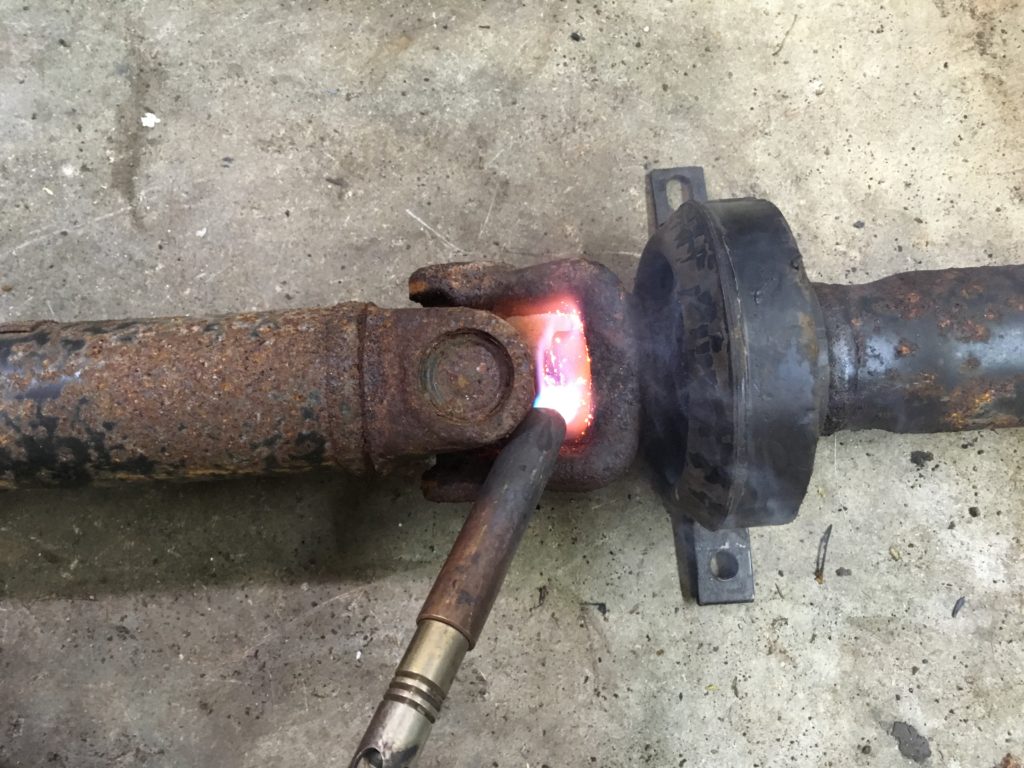

As I and others have described, you need to mark both halves of the driveshaft so you put it back together balanced, use a torch to heat up the nut holding the halves together and break the grip of the Loctite, hold the driveshaft still with a bench vise or a pipe wrench, then use a narrow 15/16″ wrench on the nut. I wind up standing on both the pipe wrench and the driveshaft, and putting a section of pipe on the ear of the 15/16″ wrench to get enough leverage.

When removing the driveshaft coupling nut, heat is not just your friend, it’s your lover.

Holding the driveshaft with a pipe wrench.

The driveshaft, separated.

But that’s just the beginning. Once the driveshaft has been separated, you still need to pull the old center support bearing off. You can try using a puller, but all that does is rip the rest of the CSB assembly off the bearing itself. I generally wind up gently tap-tap-tapping the bearing off with a hammer while rotating the shaft around so the bearing doesn’t get cocked.

The detritus of the CSB removal party.

Once the CSB was off, I needed to order a replacement. I immediately came face-to-face with that “originality” issue. A new OEM CSB is available from BMW, either through the dealer or vendors like Maximillian, but it’s expensive; list is $250, street price is about $218. Aftermarket parts are as low as $15. You can spend an evening reading on bmw2002faq and other sites about how most dealer parts aren’t manufactured by BMW and are instead sourced from a 3rd party and then bagged and boxed. You can also read about which CSBs from aftermarket suppliers have a poor reputation and which appear to be pretty good. You can make up your own mind, but I’m simply not willing to pay ten times the price if there’s no indication of commensurate quality. I ordered a Febi (who may well be supplying the OEM parts) CSB for less than twenty bucks and installed it. I was, obviously, delighted when I drove the car and the vibration at 20 mph was completely gone.

However, to drive Hampton further than around the block, continue the sort-out, and stay out of trouble, I really needed to register it. I had the New York title from the original owner, but there was a question: How much of the value of a 48,000-mile original-owner car tied up in the “original owner” part, and does that go away if, when I sell it, it’s purchased from me and not the original owner? The woman I bought it from certainly thought the “original owner” part was a big deal, and that’s part of the reason why she was surprised when I wouldn’t go for a profit-sharing arrangement where I sorted out the car for her, helped her sell it as her original-owner car, and we split the money.

When a car is registered in Massachusetts (or, I imagine, any state that issues titles regardless of the age of the car), you turn in the previous owner’s title and get a new one. But I realized that I could do what I did with the Lotus and register the car in Vermont, the advantage here being that that would let me keep the paper copy of original owner’s title.

The more that I thought about it, the more I decided that it didn’t really matter. It wasn’t her original title anyway; she’d bought the car in New Jersey in 1973 and re-titled it when she moved to New York in 2004, so, although it’s part of the provenance, it’s not that big of a deal. But more to the point, I’d bought it, so it was no longer an original-owner car. I’d already made that bed when I bought the car outright instead of entered into a profit-sharing arrangement with her, and now the proper thing to do was to lie in it. Yes, theoretically I could simply not register it at all, and, in the spring, sell the car on an “open title,” but that’s kind of shady, and it meant I couldn’t legally drive it. The older I get, the more risk-averse I am, and the more I fall on the side of spending the money and driving the car without looking in the rear view mirror worrying if I’m about to get pulled over and my registration and VIN checked.

As I’ve written, Massachusetts assesses a 6.25% sales tax not on what you paid, but on the NADA low book value of the car (which, for a 1973 BMW 2002, is $11,600). I decided that I should just run down to a MA RMV, write the check, and be done with it. I had some time one morning, so I went to the RMV. They’re usually pretty good; you wait in a triage line, then take a number, and once it’s called, it’s usually just a few minutes. And despite the bad reputation of most RMVs, the people at the windows are usually very helpful and courteous.

I swear I am not making up the fact that I got a Massachusetts RMV clerk with narcolepsy. Seriously. He kept nodding off in the middle of the transaction. I was standing at his window for nearly 15 minutes while he entered numbers into the keyboard, dozed off, and continued.

When he was done and told me the amount, to my stunned surprise, it was lower than I’d expected. I didn’t ask questions. But once I was outside, I looked at the receipt. He’d charged me sales tax not on the book value, but on what I’d actually paid. I didn’t think this was even possible. It was totally worth the extra 12 minutes.

Legal!

With plates in my possession, I checked the inspection-related systems. I needed to replace a bad horn, but that was it. It passed inspection easily.

By that afternoon, I was driving Hampton around Newton like it was a real car. There are still some small vibrations, likely from flat-spotted tires, and I haven’t yet driven the car at highway speeds, but, man, so far so good. Incredibly, the brakes feel just fine, not at all like they’ve been sitting for ten years (the benefits of indoor storage). It’s not pulling to one side due to stuck calipers or plugged flexible lines. The clutch feels a bit high, though it isn’t slipping. There’s a very small hesitation at even throttle. That floaty boaty feeling in the likely-original suspension is partially due to a front strut that feels like it’s blown or very weak. And of course, until the door lock grommets are replaced, it sounds like the doors are packed with loose coat hangers. But that’s about all that stuck out. A video can be seen here.

So, on the happy-dance-to-what-did-I-just-do scale? Total happy dance.

And yet… “What did I just do” encompasses not only buying Hampton, but selling Kugel, the ’72 tii I’ve owned for nine years, the car that’s on the cover of my first book, road trip veteran of MidAmerica 02Fest, Oktoberfest, and the Vintage. It’s difficult to imagine driving Hampton to, say, the Vintage in Asheville, since much of the car’s value is in its sub-50,000 miles, and I’d roll over that on one trip.

So I sold a well-sorted ’72 tii to pick up a nearly identical-looking car that I basically can’t drive? Siegel, what are you thinking??

Actually, that’s a good question.—Rob Siegel

_________________________________

Rob’s new book, Resurrecting Bertha: Buying Back Our Wedding Car After 26 Years In Storage, was just released and is available on Amazon here. His other books, including his recent Just Needs a Recharge: The Hack MechanicTM Guide to Vintage Air Conditioning, are available here on Amazon. Or you can order personally-inscribed copies of all of his books through Rob’s website: www.robsiegel.com.