With its corporate headquarters located directly across the street from the site of Munich’s Olympiapark, BMW is a natural partner for the Olympic movement. When the Games were held in Munich in 1972, BMW’s battery-powered Elektro-Auto 1600 paced the marathon and speed-walking events.

In 1996, the Olympic Games were held in Atlanta, Georgia, just two hours up the highway from BMW’s new assembly plant in Spartanburg, South Carolina. That presented BMW of North America with the perfect opportunity to sponsor the Games, supplying a fleet of cars and motorcycles for the nationwide Torch Rally as well as the Games themselves. That sponsorship resumed when Salt Lake City hosted the 2002 Winter Olympics, and parent company BMW AG followed with its own sponsorship of the London Olympic Games in 2012.

Those efforts put BMW in front of global audiences during the immensely popular Games, but they didn’t mark the limits of BMW’s Olympic effort. As sports came to rely on technical innovation and data analysis, BMW’s expertise became a valuable commodity for Olympic athletes. In 2008, BMW AG lent its Munich wind tunnel to Germany’s bobsled and luge teams, helping them increase their aerodynamic efficiency in advance of the 2010 Winter Games in Vancouver, British Columbia. The result? Three gold, three silver, and two bronze medals for the German athletes.

When BMW of North America became the Official Mobility Partner of the US Olympic Committee in 2011, the company wanted to do more than simply provide the team with vehicles. Like BMW in Munich, BMW NA wanted to lend its technical expertise to athletic performance. Somewhat surprisingly, USA Track & Field asked for help with the long jump, an event that involves nearly no equipment—just a jumper, a take-off board, and a sand pit. Despite that simplicity, world long jump records have proved remarkably durable. Bob Beamon’s world record of 29.2 feet stood from 1968 to 1991, and Mike Powell’s record of 29.4 feet had stood for twenty years when BMW began helping USA Track & Field athletes try to break it.

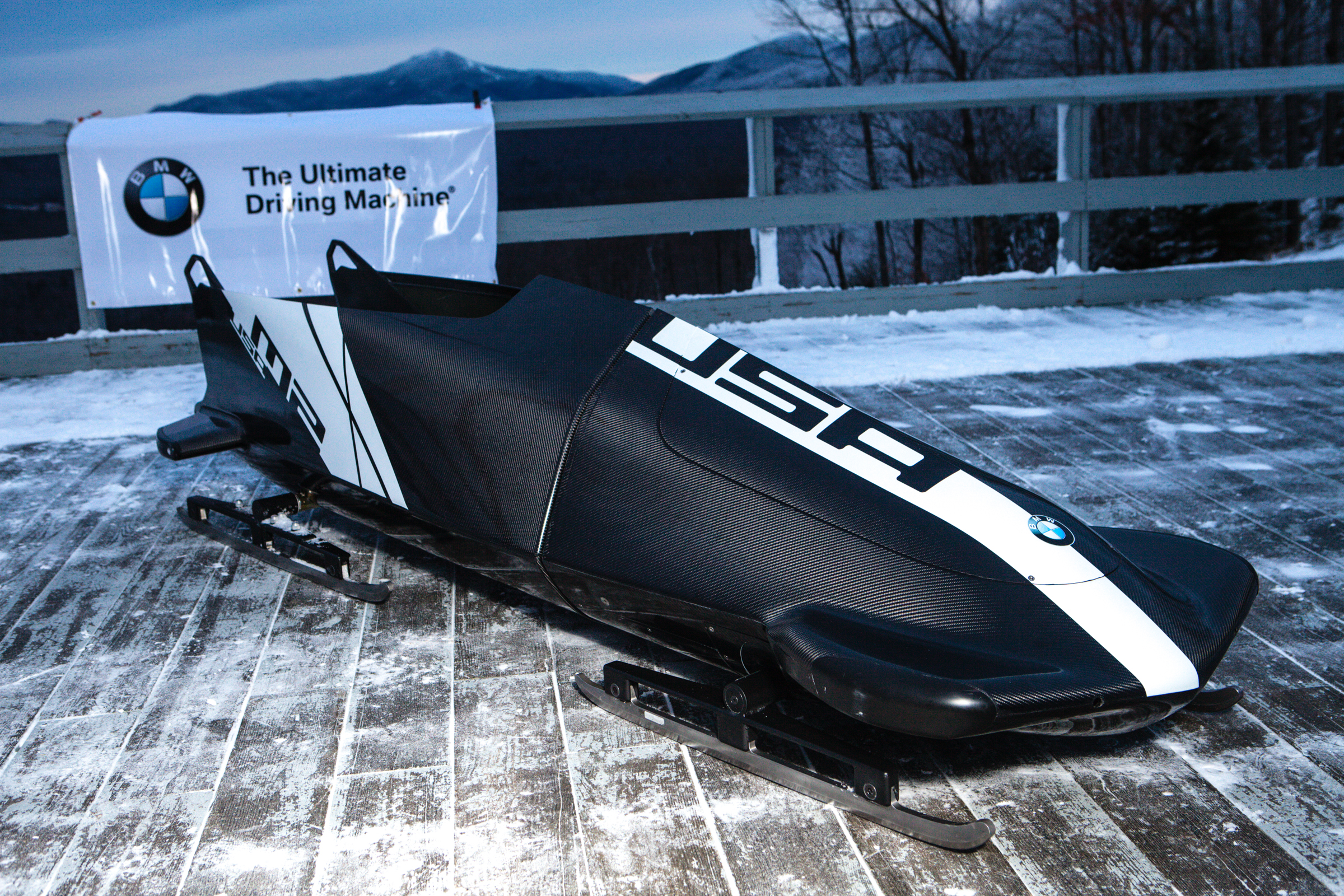

20 Dec. 2012: BMW unveils and tests the M2 2-man Bobsled at the Olympic Sports Complex in Lake Placid, N.Y. (Photo/Todd Bissonette)

Technique and training play an outsized role in an athlete’s success, and long jumpers were accustomed to analyzing their form using film or video. The utility of that method was limited, however, as it couldn’t tell them their speed down the approach or at launch, and neither could it precisely analyze their take-off angle.

Enter the BMW Technology Office in Palo Alto, California, where advanced technology engineer Cris Pavloff decided to apply the camera techniques used on BMW’s cars to prevent accidents. Rather than a single camera angle, this equipment provided a “stereo” view of an athlete in motion. Initially, this resulted in an information overload, which Pavloff solved by having the athlete wear a white cap that could be tracked by the cameras. That made the data usable—and in real time.

“The feedback this tool is able to provide during a practice, as opposed to days after, will enable me to make minor adjustments in my jumps that could equate to significant performance gains,” said Bryan Clay, who won the Olympic gold medal in decathlon at the 2008 Games.

Alas, Clay didn’t make the US Olympic Team in 2012, but American Will Claye won a bronze medal. Claye didn’t break the world record, however, and neither did the athletes who took gold or silver ahead of him. As of this writing, Powell’s 1991 long jump record still stands.

Pavloff and the BMW Technology Office provided similar “stereo-vision” technology to USA Swimming, which used it to analyze a swimmer’s dolphin kick within the 15 meters that swimmers are allowed to remain underwater after the start. Swimming is always a strong sport for Team USA, and the American athletes came home from London with 16 gold, eight silver, and six bronze medals.

In advance of the 2014 Winter Games in Sochi, BMW DesignworksUSA would apply its technical expertise to build a two-man bobsled for the US Olympic Team. “This is a uniquely challenging project for BMW, yet is as close to automotive design as possible,” said Michael Scully, then the Creative Director for Global Design at BMW DesignworksUSA in Southern California. “That allows us to utilize our race car experience combining aerodynamic design, new materials, CFD (Computational Fluid Dynamics) testing and evaluation, and wind tunnel testing for a non-automotive vehicle.”

Scully chose to build the sled not in the usual fiberglass but in lightweight carbon fiber. BMW had more expertise with carbon fiber than most auto manufacturers, having elected to use it for the chassis of its i3 and i8 automobiles as well as the America’s Cup yachts BMW built for Oracle Racing. As in other disciplines, carbon fiber’s light weight would allow the bobsled chassis to situate weight in the ideal position to optimize performance, though most improvements would be gained through aerodynamic efficiency. In this area, Scully’s team was able to compare data from CFD testing with that generated in the wind tunnel, correlating the two data sets to ensure accuracy and reduce drag from specific components.

20 Dec. 2012: BMW unveils and tests the M2 2-man Bobsled at the Olympic Sports Complex in Lake Placid, N.Y. (Photo/Todd Bissonette)

While the chassis was getting the high-tech treatment, so was the bobsled’s steering mechanism. Though the driver controls the sled via a rope attached to the front runners by D-rings, BMW NA’s IMSA race team, BMW Team RLL, improved the steering mechanism to which the ropes are attached, and lowered it for better weight distribution.

“The cool thing about our new BMW sleds is that they really smoothed out the steering mechanism,” said driver Elana Meyers Taylor, who’d raced a pre-BMW bobsled to a bronze medal in the 2010 Games. “If that motion is really jerky, a lot of friction is created as the sled moves across the ice, which makes it hard to have a good, smooth line and time. But BMW has really worked hard to make it a smooth mechanism, which allows us to make mistakes and still be fast. It’s given us the opportunity to compete week after week at the highest level.”

The BMW-built bobsleds raced for the first time at the 2013 World Cup in St. Moritz. Although they didn’t triumph outright, they scored second-place finishes for Meyers Taylor and Katie Eberling, and Steven Holcomb and Curt Tomasevicz. (Prior to BMW’s involvement, Holcomb had driven Team USA’s four-man bobsled to a gold medal at Vancouver in 2010.)

At Sochi for the 2014 Winter Olympics, Meyers Taylor and Lauryn Williams raced to a silver medal, while Jamie Greubel Poser and Aja Evans took bronze. “When I come down the track and knew I’d made mistakes, I realized I would have to be happy with the silver medal,” Meyers Taylor said. On the men’s side, their compatriots Holcomb and Steve Langton scored another silver medal—the USA men’s first in 62 years—racing their BMW-built bobsled.

BMW of North America continued to partner with Team USA through 2016, and DesignworksUSA made another big effort to improve the team’s performances in Rio de Janeiro. This time, the impetus came from Team USA’s Paralympic athletes.

“I went to BMW Designworks to help pitch the idea of building a racing chair for the team,” said Paralympic wheelchair racer Josh George, who’d won a gold medal at Beijing in 2008. “Five minutes into our very first conversation, they were rattling off ideas. I’d never gotten to work with a group of people that wholeheartedly dove into my world and were able to offer productive, insightful feedback. It was amazing.”

That was necessary, said Designworks Associate Director Brad Cracchiola. “We needed to know about the intricacies of the sport. There are thirteen rules and regulations that cover the design of a racing wheelchair, and we would have to work with those as well as find out what worked well for the athletes. It looks fairly simple, but it’s far more technically complex.”

As Scully’s team had with the bobsled, Cracchiola’s team used BMW’s racing experience to maximize the aerodynamic efficiency of the chair and the athlete. Instead of the traditional aluminum or titanium tubes, they crafted the chassis in carbon fiber, which increased stiffness, reduced weight, and improved aero performance by allowing components to be formed in different shapes. As they would a racing car, they also molded a carbon fiber seat to each athlete’s body, giving them maximum security and perfect alignment when they hit the wheels with their hands to gain forward momentum.

RIO DE JANEIRO, BRAZIL – SEPTEMBER 14:Tatyana McFadden of the United States competes in the Women’s 5000m – T54 Heat on day 7 of the Rio 2016 Paralympic Games at the Olympic Stadium on September 14, 2016 in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. (Photo by Friedemann Vogel/Getty Images)

Before the Rio Games, Team USA’s Tatyana McFadden tested the BMW chair, which she found much improved over her previous equipment. “The new chair was very stiff,” McFadden said. “The old titanium chairs had a lot of flex over time, and a lot of drag. It was built to be semi-aerodynamic, but it wasn’t as aerodynamic as we thought it was.”

Along with the racing chair, the athletes’ gloves came in for analysis at Designworks. Previously, each athlete had made the gloves themselves, using a moldable but hard-setting putty to create a striking surface that would fit precisely the ring that propels the wheels. BMW replaced that putty with lightweight, heat-resistant material formed with 3D printing technology, which allowed Designworks to perfect the gloves incrementally until they were perfect for each athlete.

“I’ve been racing with the U.S. team since 2004, and I’ve gone through pairs of gloves I’ve had to make myself,” George said. “There’s always a huge worry factor: Are the new gloves going to be worse than those you’re currently using? BMW changed that, and it’s just a huge step forward for us.”

George didn’t win a medal at Rio, but other athletes racing the BMW-designed chairs did. McFadden won four golds to add to the three she’d won four years earlier in London, while her teammate Chelsea McClammer racked up two silvers and one bronze medal. BMW of North America also sponsored Olympic swimmers Nathan Adrian, who won two gold medals in the relay events, and Maya DiRado, who won two golds, one silver, and one bronze in individual races.

BMW of North America’s sponsorship of Team USA expired in 2016, but the impact of Designworks’ efforts to improve the equipment used by American athletes continues to reverberate throughout the Olympic and Paralympic movements. BMW of North America’s technology expertise helped Team USA Olympic and Paralympic athletes bring home 40 medals. The design world noticed, too: In 2016, the BMW-built bobsled won a Red Dot award, the equivalent of an Oscar for designers, and in 2017 the racing wheelchair won another Red Dot award.

Tags: Olympics technology