If you were following the business news on March 16, 2009, you might have noticed an interesting transaction involving SGL Carbon, the world’s largest supplier of carbon fiber and carbon fiber products, including automotive brakes. On that date, the SKion investment firm spent approximately €140 million to acquire more than 5 million shares in SGL, or 7.92 percent of the company. With it came a seat on the SGL board for SKion principal Susanne Klatten, a 12 percent owner of BMW and the daughter of BMW’s 1959 savior, Herbert Quandt. (With her siblings, Klatten owns just under half of all BMW shares.)

Klatten’s investment constituted a masterstroke of vertical integration. BMW had begun using carbon fiber on its M cars in 2005, when the E63 M6 was equipped with a roof and bumper supports in carbon fiber reinforced polymer (CFRP). And in 2007, BMW Chairman Norbert Reithofer announced a multi-faceted program called Efficient Dynamics that aimed to improve all aspects of BMW’s vehicles, from engine performance to aerodynamics, and which promised a significant weight loss, as well. Carbon fiber would help BMW realize that, and it would also be essential to containing the weight on the battery-electric Megacity Vehicle being developed under Project i, another initiative that began in 2007.

The supply of suitable carbon fiber isn’t infinite, however, but Klatten’s investment in SGL Carbon would ensure that BMW had access to as much of the material as it needed. It would also ensure that BMW’s competitors didn’t, especially after Klatten raised her stake in SGL Carbon to 22 percent shortly after making her initial investment. In 2009, BMW and SGL formed a new joint venture, SGL Automotive Carbon Fiber, in which BMW held 49 percent of shares.

On July 7, 2010, SGL Automotive Carbon Fiber broke ground for a $100 million plant in Moses Lake, Washington, a joint venture between SGL and BMW. The site was chosen not for its proximity to SGL headquarters in Wiesbaden, Germany or to BMW’s plants in Bavaria and beyond, but for the clean, abundant, and relatively inexpensive hydroelectric power generated by dams along the Columbia River.

As BMW Board Member for Finance Friedrich Eichiner announced at the plant’s groundbreaking, “Lightweight construction is a core aspect for sustainable mobility improving both fuel consumption and CO2 emissions, two key elements of our EfficientDynamics strategy. By combining the know-how of SGL Group and our expertise in manufacturing CFRP components, we will be able to produce carbon fiber enhanced components in large volumes at competitive costs for the first time. This is particularly relevant for electric-powered vehicles such as the Megacity Vehicle.”

BMW wasn’t alone in recognizing carbon fiber’s potential, however. In February 2011, rival automaker Volkswagen and its supplier Voith combined to acquire 17 percent of SGL, threatening Klatten’s control. She countered by increasing her holdings to 27.3 percent, and with it gained veto power over any decisions made by the SGL board. That November, her position was strengthened by BMW’s institutional acquisition of an additional 15.16 percent of SGL; with Klatten, BMW now controlled nearly half of this essential manufacturing resource, and it would increase its stake still further over the next few years. In April 2013, Klatten would be named Chairperson of the SGL board of directors.

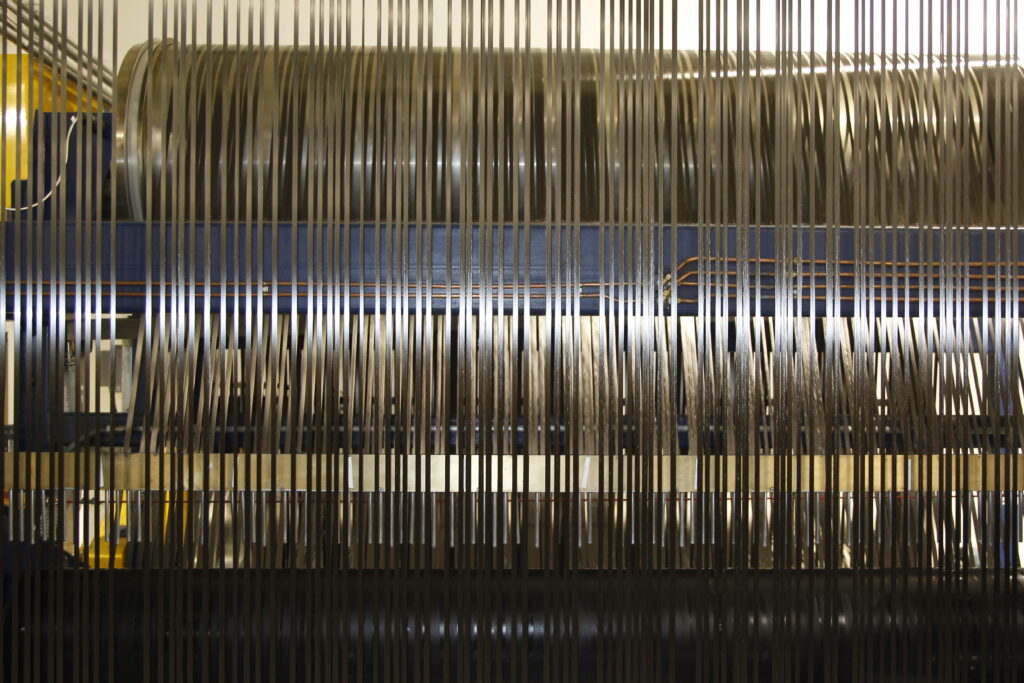

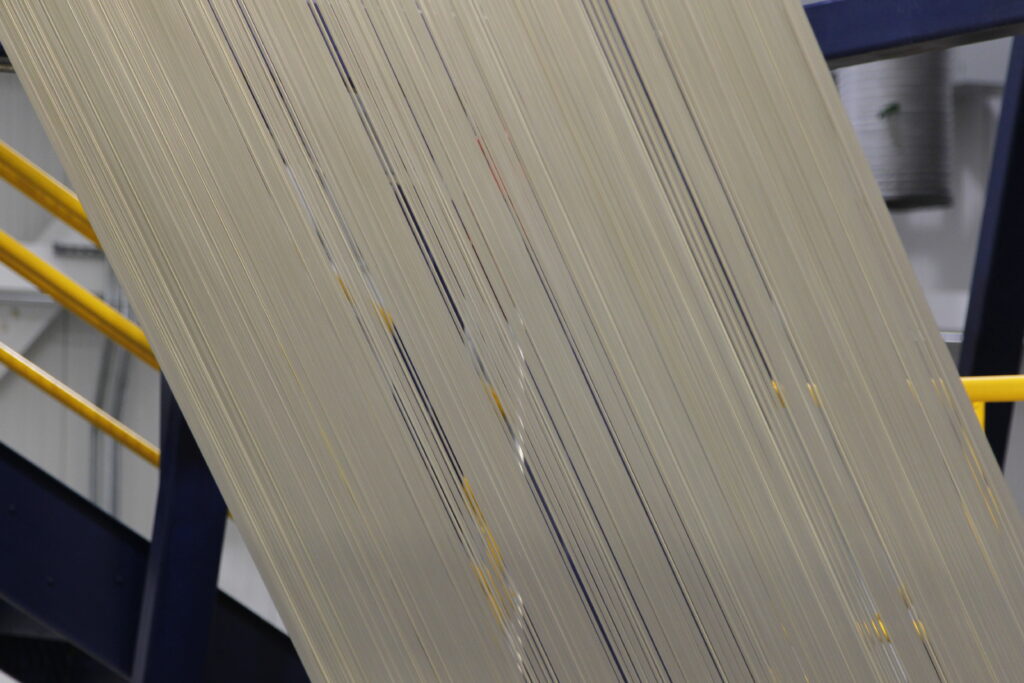

The Moses Lake plant became operational in 2011, just as Klatten and BMW were expanding their control over SGL as a whole. Then and now, the plant handles the second stage of a production process that begins with polyacrylonitrile (PAN) precursors spun into threads at SGL factories in Otake, Japan and Lavradio, Portugal. At Moses Lake, those precursors are converted into carbon fiber through exposure to extreme heat—first about 460 degrees, then 1,300 degrees, and finally 2,550 degrees—which doesn’t burn the fibers but expels all of their non-carbon components and leaves long chains of interlocked carbon atoms. These carbon fibers are then sent to SGL’s factory in Wackersdorf, Germany, where they’re woven into sheets that can be formed into parts at factories like BMW’s plant in Landshut, Bavaria. There, BMW had devised new manufacturing processes, including a resin transfer molding process that allowed carbon parts to be produced in about one minute, and which didn’t require the use of an autoclave for curing.

- BMW i Production of carbon fiber at Moses Lake expanded in 2013.

- SGL Automotive Carbon Fiber in Moses Lake (09/2011)

The start of operations at Moses Lake and the collaboration with BMW represented “a major renaissance and paradigm shift for the automotive industry,” said Andreas Wuellner, SGL’s Managing Director for Automotive Carbon Fibers.

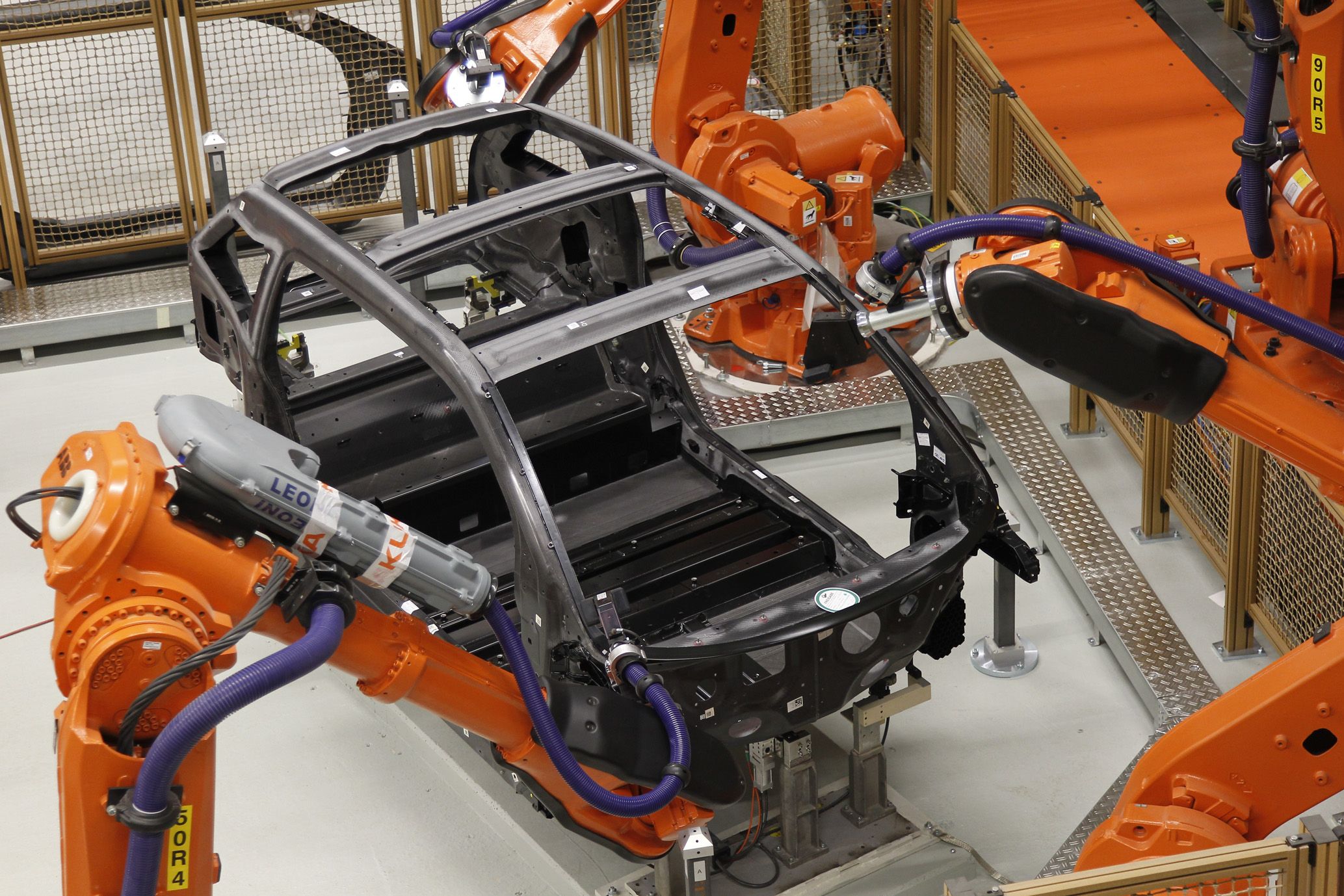

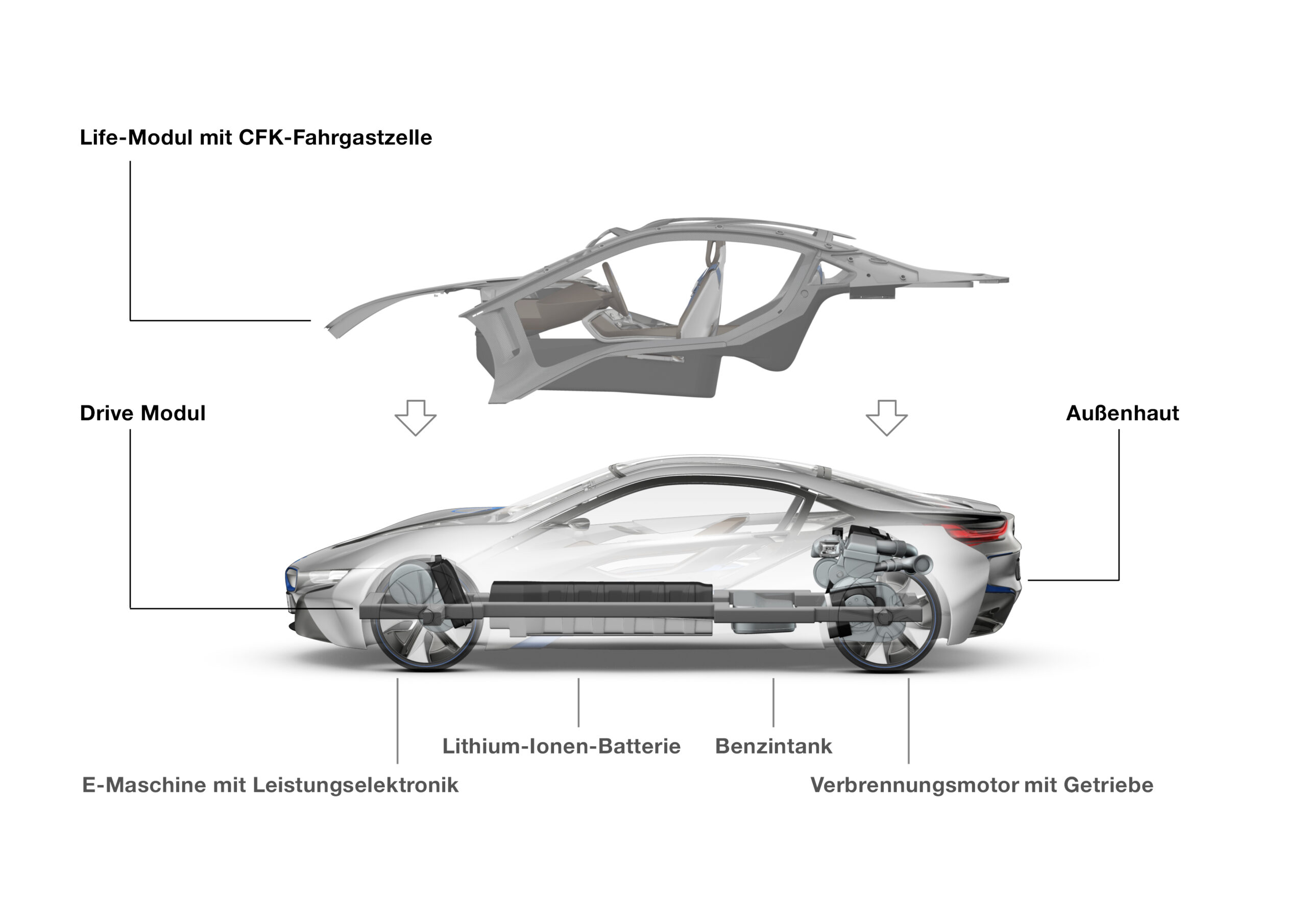

The first products of the SGL-BMW partnership were indeed revolutionary. The carbon fibers created at Moses Lake were used to build the chassis for BMW’s all-new Megacity Vehicle, which went into production in 2013 as the i3. The i3 used what BMW called “Life-Drive Architecture”, in which the carbon-fiber body shell constituted the “Life Module” which provided the crash structure for the occupants while the aluminum battery tray, electric powertrain and suspension comprised the “Drive Module”. It was the first series-production vehicle to use a CFRP body shell, and it was followed in 2017 by the similarly constructed gasoline-electric hybrid i8 sports car in 2014.

In both cases, construction of the CFRP body required fewer parts and less time than a steel body, though it remained significantly more expensive despite the advantages of vertical integration. In the case of the i3 and i8, however, CFRP was essential to keeping the cars within their weight targets. BMW had set a target of 2,750 pounds for the i3, which the production car met easily at 2,635 pounds. That allowed BMW to equip both cars with smaller and less expensive batteries, balancing the cost.

Interestingly, Boeing made a similar calculation when it chose carbon fiber for the fuselage of its 787 Dreamliner jet. In 2012, BMW and Boeing announced their plans to collaborate on the recycling of carbon fiber, enhancing the material’s environmental friendliness at the end of its life cycle.

Carbon fiber would be used more sparingly in BMW’s conventional cars, and only where its lighter weight would make a real difference to performance. In 2014, the new E9X M3 and M4 used carbon fiber for their driveshafts, roof panels, and bumper bars, saving 36 pounds from those three components alone. In the F82 generation that followed, the limited-production 2016 M4 GTS would be equipped with CFRP aerodynamic elements, and it could be ordered with optional carbon fiber wheels that saved 14.5 pounds of unsprung weight.

BMW i8 Concept, LifeDrive-Architecture (07/2011)

In the non-M sector, BMW equipped the sixth-generation 2015 7 Series with a “Carbon Core” chassis, which combined CFRP with steel and aluminum to maximize rigidity while minimizing weight. That hybrid approach was undoubtedly expensive, however, and it wasn’t applied to other cars in the BMW lineup, nor on the seventh-generation 7 Series.

Indeed, BMW was shifting from widespread use of carbon fiber, and in particular from bespoke carbon fiber body shells like those used on the i3 and i8. Discontinued in 2022 and 2018, respectively, those cars would remain outliers in the BMW automotive universe. Though the forthcoming Neue Klasse electric cars will be revolutionary in their own way, they’re unlikely to make extensive use of carbon fiber.

In 2017, SGL and BMW announced that SGL would purchase BMW’s 49 percent stake in its Automotive Carbon Fibers joint ventures in Germany and the US. BMW would retain its 18.3 percent shareholding in SGL Carbon, and the companies would continue to collaborate on smaller parts, like the enclosures for BMW’s EV batteries. (Volkswagen continues to hold 7.4 percent of the company.)

BMW’s decision had a strongly adverse effect on SGL’s fortunes. “Due to the termination of a supply contract and weak demand from the automotive industry, Composite Solutions was unable to repeat its good figures from the previous year,” said SGL CEO Dr. Torsten Derr last summer. “We do not see any recovery for the business unit Carbon Fibers even after six months in 2024.”

It was an interesting experiment, one that captivated tech-minded enthusiasts, but it’s one that BMW is unlikely to repeat, especially as energy costs continue to rise worldwide.