In 1975, Ammirati & Puris proclaimed BMW “The Ultimate Driving Machine,” setting off one of the greatest ad campaigns of all time. The synergy between the agency and BMW of North America saw BMW’s US automobile sales increase nearly fivefold over the next decade, a remarkable achievement. As the 1980s wore on, however, the fabric began to fray. The rising value of the Deutschmark made German cars more expensive in the US just as a wave of affordable luxury cars was arriving from Japan. From a high of 96,759 cars in 1986, BMW of North America’s sales fell to just 53,343 cars in 1991.

Was advertising to blame? Probably not, but any creative relationship can become stale over time, especially when it’s subject to pressure from above. BMW NA’s advertising independence had never sat well with the parent company in Munich, which had long defined its cars with “Freude am Fahren,” or “Driving Pleasure” and preferred its subsidiaries to do the same.

“The request to get rid of Ammirati & Puris was emanating from Munich,” said Carl Flesher, then BMW of North America’s Vice-President of Marketing. “They felt we needed fresh thinking in terms of advertising, and there was even a request of me to drop The Ultimate Driving Machine [tagline]. I refused. I fought for Ammirati & Puris, saying they are an excellent agency, they have a feel for the brand, and advertising is not going to turn this business around. It’s got to be through product and pricing.”

Nonetheless, Flesher knew that advertising remained critical. “I had Harvard do a study on what happens when companies put an enhanced effort into their marketing when sales are off like that. They showed unequivocally that when demand goes down, companies that invest in themselves the most come out first, and go higher.”

With sales dropping precipitously, BMW of North America made major personnel changes in its executive suites. Flesher left NA to become Head of Public Relations for the nascent BMW Manufacturing, and he was replaced as Head of Sales and Marketing by Victor Doolan, CEO of BMW Canada since 1987. “Soon after I arrived in the US, Karl Gerlinger, who was President at the time, was clearly instructed by BMW AG to replace the agency,” Doolan said. “As I was in charge of Sales and Marketing, I agreed to tell the agency.”

On October 27, 1992, Doolan and McGurn went to the Ammirati & Puris offices in Manhattan.

“Only Marty [Puris] was there, and we told him we were putting the account up for review,” McGurn said. “He reacted fairly calmly, matter-of-factly. Then, as we were leaving, Ralph [Ammirati] came in. We were preparing to announce the review the next day, and we had invited journalists to the BMW Gallery in Manhattan. That night, or first thing the next morning, Ammirati & Puris had resigned the account, very publicly.”

Puris called BMW’s move a “blindsiding,” and he told The New York Times that his firm wanted nothing to do with a review. That left the field wide open for new candidates, which by mid-December had been narrowed from 30 agencies to five: Earle Palmer Brown in Bethesda, Maryland; McCabe & Company in New York; McCaffrey & McCall in New York; Mullen in Wenham, Massachusetts, and TBWA in New York. McGurn told The New York Times that the agencies would be asked to develop a campaign to introduce “an undisclosed new BMW model that is scheduled to be introduced next summer.”

In February 1993, Mullen was announced as the winner. “Everyone I’ve spoken to says it was Jim Mullen himself who won the account,” said Patrick McKenna, who worked on the BMW account as a young marketer at DeWitt Media. (Following the split with Ammirati & Puris, BMW NA divided the media and creative responsibilities between two agencies.) “His office was like a former convent, and he had his classic car collection out front. Supposedly he was crying as he made his pitch—that’s how emotional he was about the account.”

Alas, Mullen’s emotion couldn’t compensate for unexceptional work from his 150-person staff, who might not have been as passionate about cars as Mullen. “They didn’t have the creative chops the brand needed,” McKenna said. Doolan concurred. “They worked hard, but the magic was missing.”

The relationship lasted just 25 months before Mullen was dropped as BMW NA’s agency of record, effective July 1, 1995. The move was announced by BMW NA’s new Vice-President of Marketing, Jim McDowell, who’d taken that post when Doolan was elevated to President in 1993. In explaining Mullen’s dismissal to The New York Times, McDowell was diplomatic: “Mullen was instrumental in moving BMW away from its late-1980’s ‘yuppie’ imagery to the industry-leading ‘smart choice’ reputation the company enjoys today.”

Indeed, BMW of North America had begun to climb out of its sales slump even before Mullen took over, but McDowell credited the firm with helping BMW NA increase its annual sales from 78,010 cars in 1993 to 84,501 in 1994. That was a good start, he told the Times, “but now we’re talking more about integrated marketing, interactive marketing, and for that we need some additional skills.”

McDowell found those skills in Minneapolis, at the Fallon McElligott agency he’d encountered as Porsche Cars North America’s planning director from 1985 to 1990, and after that as Porsche AG’s Director of Marketing. In March 1993, McDowell was lured to BMW by Helmut Panke, then Head of BMW AG’s Group Planning Division in Munich. A month later, Panke replaced Gerlinger as CEO of BMW (US) Holding Corp., and he brought McDowell with him to New Jersey.

Mullen’s advertising for BMW NA may have been effective, McDowell told The New York Times, but it had “seemed at times a little too distant, a little too aloof. We want to make it a little more accessible in a friendly way.”

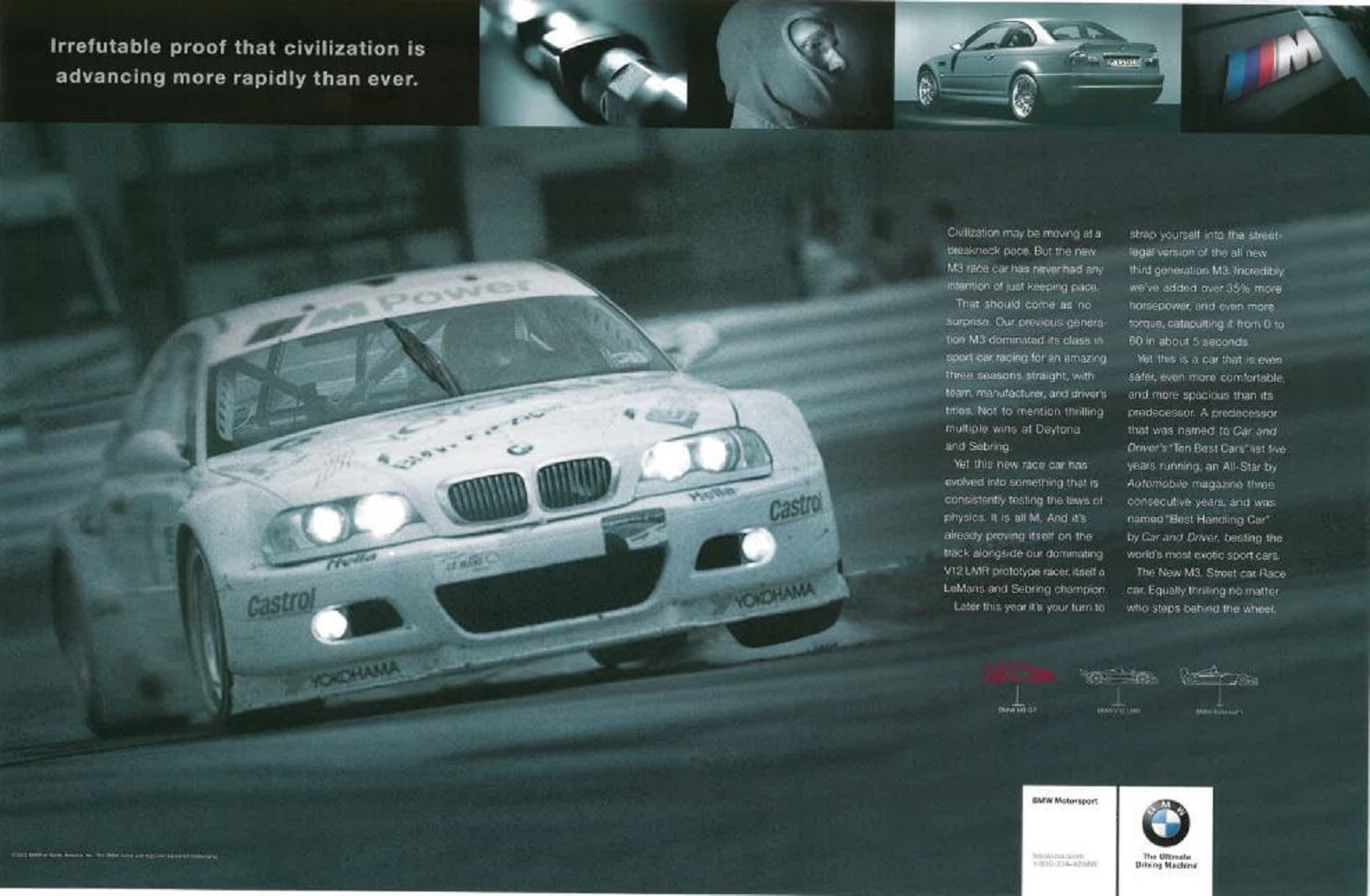

Making BMW less aloof meant making BMW’s advertising funnier, a task to which Fallon McElligot was perfectly suited. “They had a great sense of humor, and they were prepared to be a little bit in-your-face” McDowell said, “A lot of people there were very familiar with the product already—there were probably five times as many BMWs in the car park as Porsches—and everyone on the creative side had gasoline in their veins.”

The agency’s appointment coincided with the debut of the all-new Z3 roadster in the James Bond film GoldenEye. Fallon McElligot took the opportunity to lampoon British institutions with an ad entitled “Parliament,” in which bewigged lords express outrage that “Bond is driving a BMW…on the wrong side of the road!” In another television spot, various Brits were seen reading classified ads for Bond’s old Aston Martin, complete with missiles and ejector seat. “I wonder what he’s getting instead?” they ask, as the ad cuts to Pierce Brosnan as Bond, driving a Z3 in GoldenEye.

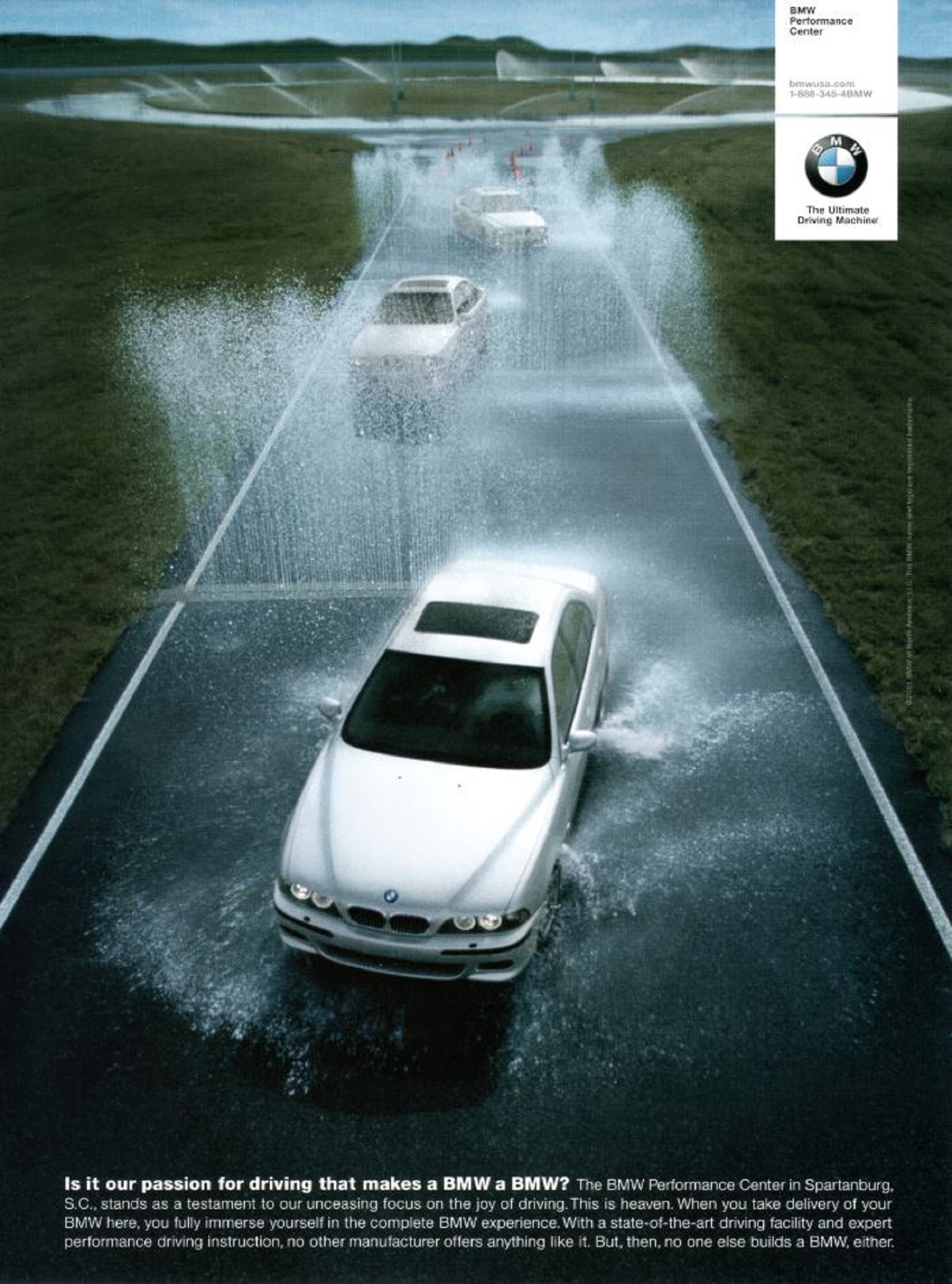

The GoldenEye connection allowed Fallon McElligot to create Bond-themed material for use by BMW dealers and direct-mail campaigns to customers. Additional Bond tie-ins were presented via BMWUSA.com, then a relatively new medium that Fallon McElligot redesigned “to perform like a BMW,” according to the agency’s President of Integrated Marketing, Mark Goldstein. That included downloadable sound effects, one of which was a recording of the M3’s engine.

“Fallon was brilliant, creatively brilliant,” said McKenna, who joined BMW NA’s marketing team in 1997. “They were also their harshest critics. They looked at their ads for the Bond Z3 and said, ‘We need to do better. We need something uniquely BMW.’”

One of the first ads to result from that self-criticism was created with cutting-edge digital effects from Northern California studio Industrial Light & Magic. The ad showed a penguin trying to scale an icy hill but sliding backward before reaching the top. Shaking its head after a second attempt, the penguin disappeared, an engine fired up offscreen, and the penguin’s wing turned on the radio on a BMW dashboard. To a Latin beat, a 3 Series sedan climbed the hill with ease. “BMW traction control. Because we all have places to go.”

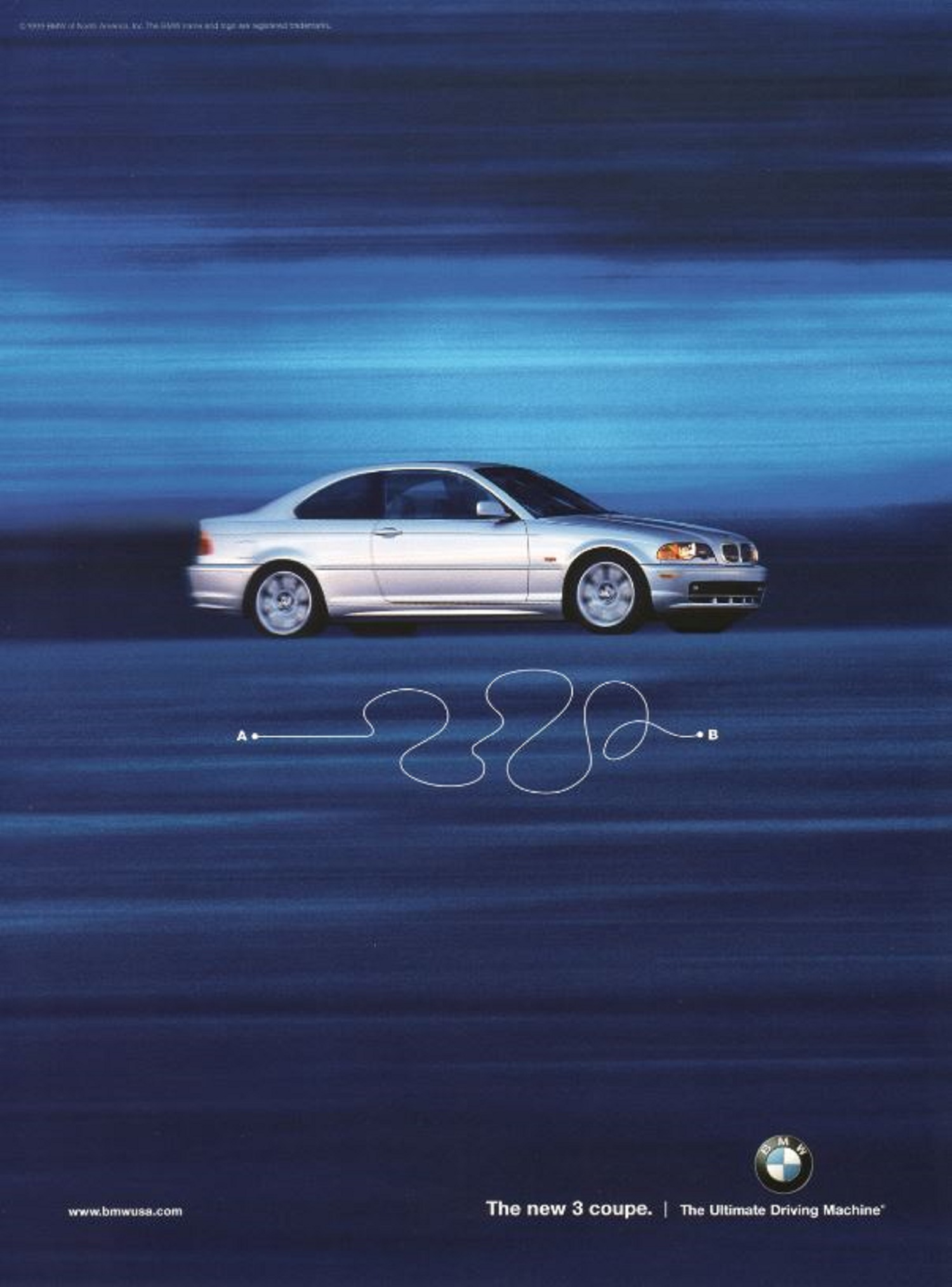

The ad was clever, as McDowell had intended, but Fallon’s next series of ads traded humor for a different kind of emotion. Stunningly filmed in black and white and backed by up-tempo electronic music, the ads highlighted the connection between a BMW and its driver. An ad for the Z3 declared, “Science. Technology. All worthless. Unless they make you feel something.” An ad for the 5 Series proclaimed the “love triangle” between the car, its driver, and the road.

“The ads were shot from the point of view of the driver on windy roads,” said McKenna, who was on hand during production. “The camera technique gave the ads a visceral feeling that had never been captured before, and each one was a work of art. They were created at a lot of expense, shot in California, and retouched in London. Every line in the copy was labored over. They paid painstaking attention to every detail.”

Fallon McElligot was outlandishly creative, and the agency found a synergy with BMW that surpassed even that of Ammirati & Puris. “They really understood the marque, and it was epitomized, at least for me, with the Z3 ad that said, ‘Happiness is not around the corner. Happiness is the corner,’” Doolan said.

Along with shooting ads from the point of view of the driver, Fallon McElligot changed the notion of who that driver might be. “Another thing we started doing is showing women driving the cars in the advertising,” McDowell said. “Back in the days when we sold 50,000 cars a year, a huge plurality of them were to men. We were perceived as a man’s car. Subtly opening up to things like having women in the photography and advertising in places that women would notice without being overly pandering were important. As we went beyond 100,000 cars per year [in 1996], a huge part of that growth was women.”

In 2001, the relationship between BMW NA and Fallon reached its apex with BMW Films, a groundbreaking series of eight short films by A-list directors like John Frankenheimer, Guy Ritchie and Wong-Kar Wai. Starring Clive Owen as The Driver ferrying celebrities including Madonna, BMW Films premiered over the World Wide Web, then only a decade old and barely capable of handling the download of each film. The Hire pushed the limits of the Web, and it expanded the boundaries of what automobile marketing could be. BMW Films were immediately recognized as works of marketing genius, and they helped propel BMW NA to annual sales of 213,127 cars in 2001.

It was a tough act to follow, even for its creators. “When we went back to conventional advertising, we were finding ourselves back into that cycle of needing to push and push to try to get something that breaks through the clutter,” McKenna said.

In early 2005, McDowell left his post as Vice-President of Marketing to swap jobs with Jack Pitney, the first Head of MINI USA. Despite the excellence of Fallon’s work, Pitney put BMW NA’s advertising account up for review that June. “Jack was so focused on change” McKenna said. “and I think when you come in as a new Chief Marketing Officer, there’s definitely a desire to put your own thumbprint on the brand.”

In addition, McDowell said, BMW AG was pressing NA to participate in a global marketing campaign rather than create its own. “There was a strong desire to have more worldwide unity, and it became increasingly likely that we would be sharing materials with Germany and other markets,” he said.

Like Ammirati & Puris in 1992, Fallon—by then known as Fallon Worldwide, having become part of the Publicis group in 2000—declined to participate in the review process. Thus ended one of the most fruitful creative partnerships of the late 20th century, and the second in BMW of North America’s thirty-year history.

Tags: advertising Ultimate Driving Machine