If one character could be said to dominate BMW’s early years in the US, it’s Max Hoffman. As BMW’s sole distributor in this country from 1962 to 1975, Hoffman was a champion of the marque, one whose belief in BMW allowed cars like the 2002 to reach a broad audience of dedicated enthusiasts. Alas, Hoffman’s true role within BMW history is as much villain as hero, however, as it was with respect to nearly all of the marques represented at one time or another by the Hoffman Motors Corporation.

Hoffman’s story begins in Vienna, Austria, where he was born in 1904. His father inherited a general store that turned into a manufacturer of sewing machines and then bicycles, and Hoffman spent his young adulthood racing on two wheels and four. At 30, he quit racing and began importing British, German, French, and Italian cars to Austria and exporting European cars to the Middle East. Hoffman did well, but in 1938, when the Nazi military marched into Austria, he left for the relative safety of Paris. Two years later, the Nazis were closing in once again, and Hoffman—whose father was Jewish—boarded a steamer for New York.

Hoffman had intended to export American-made trucks to Egypt, but when that fell through, he began making metalized plastic jewelry instead. His designs proved popular in the wartime economy, and he used his windfall to return to the automotive business in 1947. Adopting the name Maximilian—his legal name remained Mark Edwin—and dropping the final “n” from his surname, he opened Hoffman Motors’ first showroom at 487 Park Avenue, with a single Delahaye on the floor. Within a year, he’d be Jaguar’s official US importer, and he’d eventually represent 21 marques in the US. Hoffman encouraged them to build cars to suit American tastes and budgets, resulting in the Mercedes 300SL and 190SL, the Porsche Speedster, and the Alfa Romeo Giulietta Spyder, among others.

In 1954, Hoffman went to Munich, hoping to add BMW to his stable of marques. The company had begun producing cars again in 1951, and its new Oldsmobile-inspired V8 engine had been designed with the US in mind. Better still, BMW’s 501 and 502 sedans were soon to be joined by a V8-powered roadster, Grand Touring coupe and convertible, all of which were intended for export.

Hoffman was shown photos of the 528 roadster prototype, which he dismissed as so unattractive as to be sales-proof in the US. Back in New York, he decided to stage an intervention, asking German-born American designer Albrecht Graf von Goertz to produce a few sketches and send them to BMW. Thus began a relationship that would see Goertz design one of the most beautiful cars ever built, the 507 roadster, while substantially redesigning its 503 counterpart, as well.

Hoffman assured BMW that the 507, especially, would sell well in the US, and he promised to order 2,500 examples. That would certainly cover the model’s development cost, including the expensive revisions Hoffman had ordered, but that number was soon reduced to a “firm order of 1,000 cars,” then to 300 cars per year over four years. To make matters worse, Hoffman also reneged on his pre-payment commitments, even after those were reduced from $1 million to $500,000.

All of that contributed substantially to BMW’s 1959 brush with bankruptcy, which nearly saw the company absorbed into Mercedes until an investment by Herbert Quandt ensured its independence.

Making matters worse, the high retail price of these hand-built cars made them astronomically expensive by the time they reached the US. Each car retailed for nearly $10,000, as much as a far more powerful and luxurious Cadillac at the time. The demand for such an expensive BMW would be severely limited regardless of its style or performance, and Hoffman ended up importing a mere 16 507s throughout all of 1957 and ’58.

At the end of that year, BMW terminated its contract with Hoffman and gave exclusive distribution rights to Fred Oppenheimer’s Fadex Corporation, which had successfully imported the Isetta and other BMW microcars. BMW’s large cars were difficult to sell even for Oppenheimer, and in 1959 he asked to terminate the distribution agreement. At BMW’s request, Fadex held on for two more years, but sold just 1,212 BMWs during that period. In October 1961, the relationship with Fadex was finally dissolved, and BMW Automobile Parts, Inc. was set up in its place. A wholly-owned sales subsidiary seemed likely to follow, but none would materialize.

In the meantime, the 21 marques represented by Max Hoffman in the US had been reduced to just two: Lancia and Porsche, the latter only east of the Mississippi. Though he later claimed he’d given up the rest to focus on BMW, the manufacturers had severed their relationships with him one by one over the previous decade: Volkswagen in 1953, Jaguar in 1954, Mercedes in 1957, BMW in 1959, Fiat in 1960, and Alfa Romeo in 1961. Some did so because they deemed Hoffman a customer-service liability, others simply to cut out the middleman. In most cases, however, these brands (excluding BMW) dissolved their agreements with Hoffman at great expense, under terms that, in many cases, extracted hundreds of dollars for every car sold in the US until the original contracts expired.

That BMW would return to Hoffman’s embrace seems inexplicable, but the company lacked the funding to establish its own distribution network over the vast geography of the US. Hoffman had a strong advocate in Paul Hahnemann, who recently arrived from Borgward to become BMW’s new board member for sales. Undoubtedly, the contract suited both men, even as BMW protected itself by contracting with Hoffman for just three years, from March 1962 through the end of 1964. The document required Hoffman to order 1,000 cars during that period, to deliver the “powerful service” for which he was little known, to take over BMW’s parts inventory, and to maintain distribution centers on both sides of the US.

Hoffman’s reinstatement coincided with the 1962 launch of the Neue Klasse, a reasonably priced midsize sedan that promised to succeed where the V8-powered cars had failed. The 80-horsepower 1500 was underpowered for the American market, but the 90-horsepower 1800 fared slightly better, as did the 101-horsepower 2000 that arrived in 1966. Hoffman was always a fan of high-performance models, and in 1965 he imported 54 examples of the customer-racing 1800 TI/SA, more than one-quarter of total production.

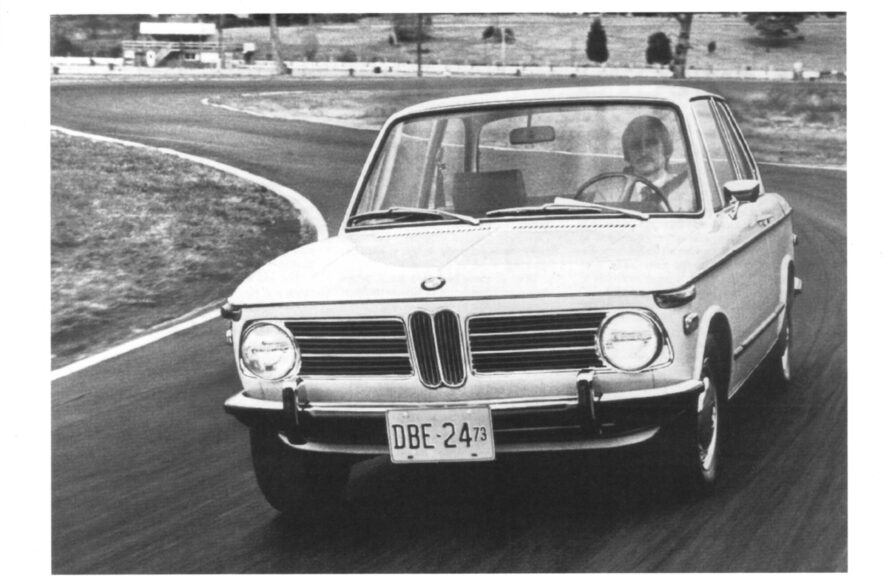

A stronger product lineup helped BMW’s exports to the US increase from just 231 cars in 1963 to 1,253 in 1966, when the first examples of a new two-door started trickling in. Hoffman didn’t think the 1600-2 was likely to succeed in this market, and he doubted that it could be sold profitably. The car caught on anyway, helped by favorable reviews in magazines like Car and Driver and Road & Track. Later, clever advertising boosted sales further by emphasizing the car’s performance with copy that touted its “100-mph cruising speed, and phenomenal roadholding.”

The arrival of the 1600-2 saw BMW’s US exports jump from 1,253 cars in 1966 to 4,564 cars in 1967, and all but 168 were 1600-2s. When that car was joined by the more powerful 2002 in 1968, sales doubled yet again, to 9,172. The 2002 became a genuine sensation, inspiring enthusiasts to create the BMW Car Club of America in Boston and the BMW Automobile Club of America in Los Angeles.

Though Hoffman has been credited with the car’s creation, the 2002 was an organic development within BMW. In Munich, Hahnemann was pushing for a sporty compact car with “something extra” at the same time that BMW engineers were fitting the small two-door with BMW’s largest four-cylinder engine. The 2.0-liter engine allowed them to improve performance over the 1600-2’s 1.6-liter engine without exceeding US emissions limits, something that a higher state of tune couldn’t achieve. Hoffman had nothing to do with its development, though he certainly welcomed its arrival. He does, on the other hand, deserve credit for the Bavaria, a stripped-down version of BMW’s large sedan that sold for under $5,000 in the US. The car proved popular, but BMW itself lost money on every Bavaria while profitable cars like the 2800 and 3.0 CS sold in exceedingly small numbers. By 1971, BMW decided to stop offering its large cars in the US altogether after 1977.

As that suggests, Hoffman’s business practices were proving problematic for BMW. He expanded the dealer network considerably, but his low bar to entry—shops that Hoffman approved for a dealership could buy the necessary signage and equipment for as little as $1,500 and could order as few as two cars—meant that many dealers were unqualified to provide knowledgeable repairs or other services. Spare parts were lacking, as well. “Hoffman wasn’t very interested in what happened after he’d sold the cars,” said Chicago BMW dealer Bill Knauz. “He didn’t pay you properly on parts, service, warranty work, etc. When it came to Max’s pocket book, Max took care of Max.”

More concerning for BMW, Hoffman’s ordering practices were erratic, causing problems at the Munich factory. Sales fluctuated more than BMW could tolerate, and they weren’t increasing at a rate that the company expected given the marque’s increasing visibility among American enthusiasts. Hoffman wasn’t particularly interested in following BMW’s directives for expansion, however, as he was making more than enough profit as things stood—more than BMW, as it happened.

Those irregularities had gone largely unnoticed until the early 1970s, when new leadership arrived at BMW headquarters. When the new board members began taking a hard look at BMW’s sales and distribution strategies, Hoffman’s days were numbered. All that remained was to extricate BMW from Hoffman’s unusually lucrative and long-term contracts.

Follow along as we continue to celebrate BMW NA’s 50th Anniversary.

Read the full article here.