There are only two cars I’ve owned twice—sold and then bought back. The first is Bertha, the 1975 2002 I bought in Austin in 1984 when I knew we were returning to Boston and wanted a big-bumpered 02 to withstand the demolition derby of Boston traffic better. (Yes, I intentionally sold a small-bumpered round-taillight car and bought not just a big-bumpered 02, but a ’75, the worst year of any 2002. Hey, it was the 80s. Questionable decisions fell like rain.) I turned it into a repository for every go-fast part hawked on the pages of Roundel, sold it to my friend Alex in 1988, bought it back in absolutely awful condition 40 years later in 2018, and resurrected it (see my book Resurrecting Bertha for the full gory story).

Okay, you know what? That first sentence is incorrect. As I think about it, I sold four cars and repurchased them. #2 was the Euro E21 323i I purchased in the late 80s, partially sorted out, sold with the warning that the buyer should immediately replace the timing belt of unknown age; he didn’t; it broke, and he had the head rebuilt; his mechanic couldn’t get it running, and he demanded that I take it back lest things get lawyerly-ugly. I figured that whatever was preventing it from running couldn’t be much, and with the rebuilt head plus rust remediation work he’d paid to have done, I’d do okay taking it back. All it needed to run was the correct plug wires, but the car was still a nightmare to resell. I wrote about “The Cursed 323i” for Roundel, and the column is in my Best Of book.

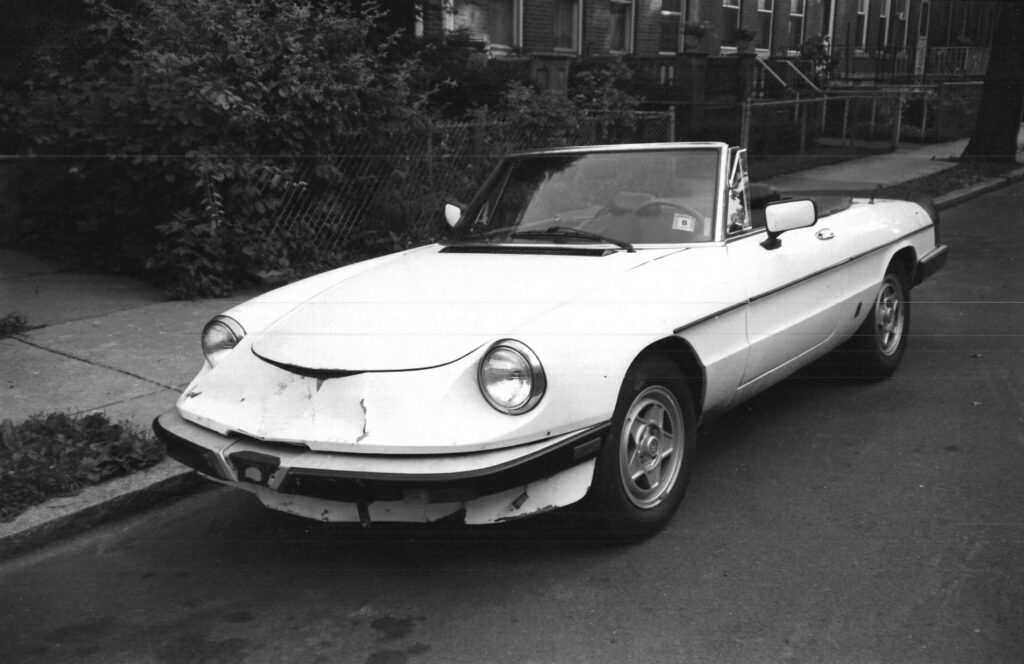

#3 was the ’84 Alfa Spider I had not long after the 323i. I replaced the head gasket and paid to have the dent in the nose repaired, and it became a fantastic summer car. When we were about to move from my mother’s house in Brighton to Newton with its one-car garage, I had nowhere to store it over the winter, so I sold it. The fellow who bought the Alfa seemed like the right buyer, as he also owned a BMW 1600 he wrenched on, but he kept coming back to me regarding things wrong with the car. (HELLO? It’s an Alfa.) When he thought I’d rolled back the odometer (I hadn’t), he had a lawyer threaten me with treble damages unless I bought the car back. It also worked out okay, as I had the car for a second unanticipated summer.

The 1984 Alfa Romeo Spider Veloce. The car that, 30 years later, made me realize I needed a Z3.

But #3 and #4 were both technicalities, mere blips triggered by unhappy lawyer-wielding owners as opposed to cars I willfully repurchased. I was right the first time. In addition to Bertha, there is only one other car I’ve bought back and held onto—Zelda the 1999 Z3.

The larger backdrop of Zelda is my love for roadsters. There’s no question that it began with the Alfa, which got me addicted to the “rolling Xanax” effect that a convertible has when you drop the top, let the sun shine on your face and the wind go through your hair, and feel your cares melt. After the Alfa, I owned an E30 convertible for a few years. I had nowhere to store that either, so my deal with myself was that I could buy it if it was my daily driver. I put Blizzaks on all four wheels and drove it over the winter. It was, of course, a terrible idea—snow on a convertible top is difficult to deal with without damaging it, and the heat loss is so dramatic that, in freezing weather, you can defrost the windshield or keep your heat warm, but not both. I was relieved when I sold it and didn’t need to face another winter daily-driving it.

It took a while after the garage got built in 2006 for me to take another run at an open-top car (well, I had the ’82 Porsche 911SC Targa, which almost counted). In late October of 2013, I bought Zelda, the Boston Green Z3 2.3. It was about as vanilla a Z3 as BMW offered, not even having cruise control, and was being sold by a woman going through a divorce. It was her car, and she loved it, but other things were taking precedence in her life. It hadn’t been driven in a while and its battery was so dead that, when jumped, the car’s electronics threw a hissy fit. Helpful hint: You can get away with the alternator trying to recharge a dead-flat battery on a primitive car like a 2002, but modern cars with control modules often freak out. You need to put a good fully-recharged battery in the car. Because of this, an expired inspection sticker, every dashboard light being on, a little mildew, and a few other odds and ends, I was able to get the car for three grand. At the time, I had no question that it was least-expensive whole intact non-salvage six-cylinder Z3 in the country.

The just-purchased Zelda in the fall of 2013.

I had five great years with Zelda. I sorted out its needs, at some point did the prophylactic cooling system replacement, and just used it locally as a stress-buster. Aesthetically, the car’s bulbous nose never lit my fire like the Alfa’s flat nose, but there was something about its cute perky shape that was especially appealing to the women in my life. My wife, her best friend Kim, my sister, and others loved it, and I loaned it out to them freely. We joked that they were “the cult of Zelda.”

My wife (right) and her friend Kim in Zelda.

Initially I had room for the car in the garage, but soon on the heels of its purchase came the Bavaria and the Euro 635CSi. I began renting other garage spaces out in Fitchburg MA, but the acquisition of cars outpaced the acquisition of the storage spaces. In the fall of 2018, I no longer had anywhere for the Z3 to over-winter, and it seemed irresponsible to let it sit outside, so I put it up for sale. Our friend Kim, the member of the Cult of Zelda who lived right around the corner from us, wanted to buy it. I agreed to sell it to her under the condition that she find somewhere to garage it over the winter. It turned out that the house she rented actually had a small but usable garage behind it, but it was shared with the person who rented the other half of the house, and was full of stuff. She worked a deal, stuff got cleaned out, and voila, over-winter storage space. I chided her for not telling me there was an garage space behind her house sooner. Although I really don’t work on cars for other people, friends are different, and Kim is a dear one. Continuing to work on Zelda allowed her to afford it, kept me connected with the car, and gave me the chance to be the person who borrowed it for stress-busting drives.

Me test-driving the car after doing some work on it for Kim.

In the fall of 2020, fortune took an odd turn. Kim’s son became Zelda’s primary driver. Whether he was brutal on the clutch or whether it was just the mileage I don’t know, but the throwout bearing clearly was beginning to self-destruct, as every engagement of the clutch pedal sounded like metal was being cut on a lathe. Then, during a late-night judgement-impaired drive home, he put the car up on a median strip. The curb strike pushed back the lower control arms, shattered the front air dam (what BMW calls the bumper cover) and took out low-hanging engine accessories, and bent all four wheels.

In some ways, this wasn’t as bad as it looks. In other ways, like the ways you’d need to pay someone to fix it, it was exactly as bad as it looks. You can see that wheel is pushed into the back of the well.

Although miraculously, none of the steel body panels were damaged, if an insurance claim had been filed, the car clearly would’ve been totaled. Thinking that this could be the end of Zelda, I agreed to take the car and see if it could be resurrected cost-effectively. While doing so, Kim and I came to an agreement on my buying the car back for what was essentially parts-car money. It spent the winter in my garage getting the clutch replaced and the front end rebuilt. The irony that I sold the car because of lack of storage space but now the car had the primo spot over the mid-rise lift and was getting a new clutch and the front end rebuilt was not lost on me.

Well, at least I had a winter project.

A bent (top) and a straight (bottom) lower control arm.

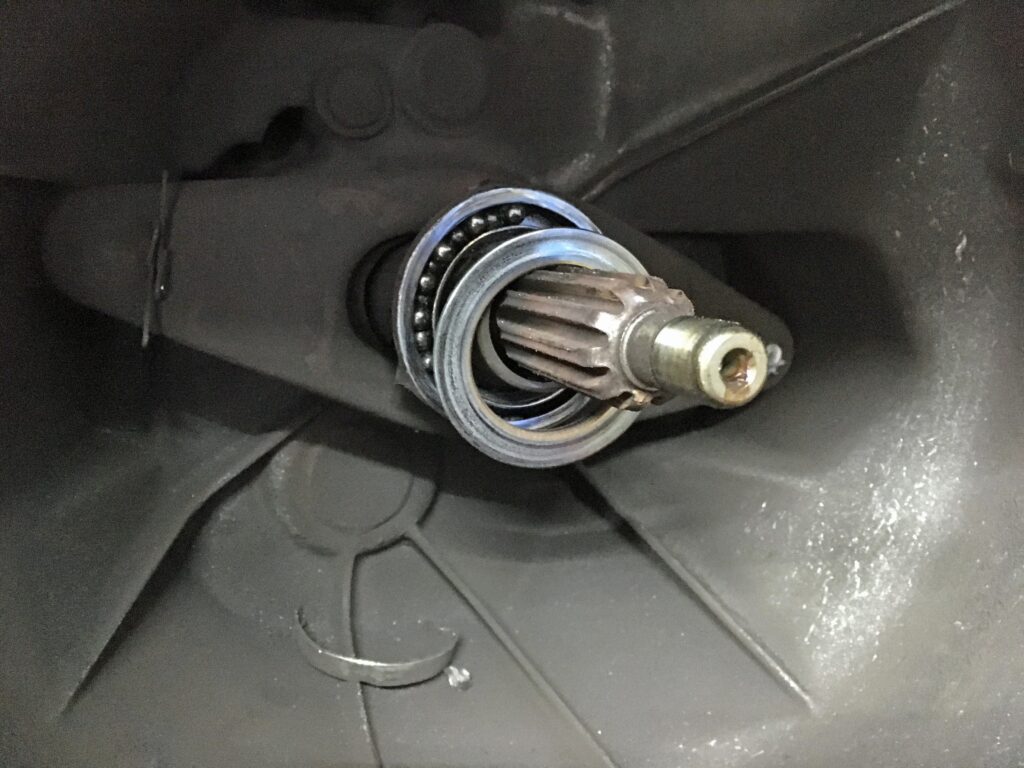

So YOU’RE the reason the throwout bearing sounded like a lathe.

When spring came, I was thrilled to have Zelda back. I drove it for several years with the shattered air dam held together with packing tape and epoxy while I searched for one from a Boston Green Z3 being parted out locally so I wouldn’t have to pay for either painting or shipping. Patience paid off when I found a car in Springfield MA that had both the air dam and the inner fender liners. Installing them largely completed the repair of the accident damage.

Before…

…and after.

Even though Zelda was resurrected, I still didn’t really have storage space for it, so my deal with myself was that I could keep it as long as it sat outside under a cover, and as long as doing so wasn’t causing egregious damage to the car. I found that a genuine BMW breathable cover did a pretty remarkable job keeping the rain from leaking through the top as well as not encasing the car in a humidity chamber, and that as long as it was parked in a section of my driveway that occasionally got sun, the mildew didn’t blossom.

Not bad for a roadster that’s forced to sit outside.

So, here we are, 11 years after I bought Zelda. I’ve now owned it longer than any of the other cars except the ’73 E9 3.0CSi (queen of the roost by a margin of nearly three decades), Bertha’s whose length of residency with me I’m not sure how to calculate, and the ’74 Lotus Europa, whose purchase in June of 2013 edged Zelda out by just a few months. It still does the rolling-Xanax thing that I need it to do. And if you ask my wife Maire Anne which of the 14 cars is her favorite, she’ll bypass the gorgeous red E9 (although she admits it would be the best car to drive to a high school reunion or visit an old boyfriend in) and head for the Z3.

However, Zelda didn’t see much use this summer and fall, as my attention was focused on the Europa, the FrankenThirty that I bought in late August, and the Lotus Elan +2 that dropped into my life on Halloween. Now that winter is nipping at our heels and the car is again relegated to sitting under a cover in the driveway, I began to wonder about the wisdom of keeping it. Z3s may well be at the bottom of their depreciation curves, and cheap slightly ratty but intact and running six-cylinder cars aren’t the unicorns they were eleven years ago. What a car is “worth” and what you can get for it if you have to sell it before the snow falls are two different things. If I had to use that second metric, it might not bring more than $2500. Then again, if I had a jones in the spring for another inexpensive Z3, it probably wouldn’t be too difficult to find one. Plus, part of me thinks that Boxsters are also likely at the bottom of their depreciation curve and maybe I should live with one of those for a while.

But the flip side of that logic is that when I think about pricing a car at a point where if I saw it for that price, I’d buy it, it tells me something: Why on earth should I sell it? I love it, it’s running great, it’s not rusty, it’s not needy, it costs me very little money to hold onto, and realistically, there’s likely no other snappy zingy intact non-rust-bucket non-money-pit little roadster could I buy for $2500.

So back under the cover you go, little Zelda. Sorry you have to sit outside, but a deal’s a deal. And hey, if it’s another mild winter, we’ll steal time when and if we can. We’ve done it before.

The whole-body Xanax effect, with refrigeration. And ducks.

—Rob Siegel

____________________________________

All eight of Rob’s books are available here on Amazon. Signed personally-inscribed copies can be ordered directly from Rob here.