I responded to two questions this week. One was about voltage regulator failure in a 2002. The person said that the car’s radio was going haywire and there was a strong smell of sulphur. When he used a multimeter to check the battery with the engine running, it read 17 volts. The fellow knew that this was the textbook symptom of a voltage regulator failing in the stuck-closed position (something I encountered in a road-trip companion’s car on the way home from The Vintage), but he was surprised because it was a brand-new solid-state Hella voltage regulator, one of those small ones that’s about half the height as the original unit. I and a number of other people responded that these units have a reputation for being junk, and that he’d be better off with a tested-as-good original mechanical regulator, or converting to a two-wire alternator with an internal regulator.

The other question was from someone who had the opportunity to buy a set of the original factory 2002 manuals in the two blue binders. Someone chimed in that original factory manuals are coveted because the quality of the photos and the wiring diagrams are much better than in a photocopy (or in the online PDF copies). I agreed about the picture quality, but I offered my opinion that, these days, the information in the manual isn’t as valuable as it once was. Most 2002 repairs are very well documented on bmw2002faq.com, and the manual contains pages and pages of anachronistic photos of the coil firing response from the Frankenstein’s-lab-like Sun engine analyzer and things that almost no one does like rebuilding a 4-speed gearbox or an original Solex two-barrel, but has nothing about newer repair issues such as angle-torquing the head bolts, or installing a 5-speed or an electronic ignition, or the dangers of urethane bushings turning your car into a squeakfest. Yes, I have a set that I occasionally consult for something obscure, and yes I’d certainly recommend snatching up a set if they’re inexpensive, but if the seller is asking hundreds of dollars, I’d be circumspect about spending the money on this as opposed to something the car really needs.

The factory manuals are useful and often come up for auction on eBay, but I’d never advise paying this kind of money for them.

Yeah, no one looks at these.

However, I forgot about one very cool trick that’s in the factory manual about testing the alternator. And that’s the subject that ties these two topics together.

I’ve written many times over the years—most recently in my article about the return trip from The Vintage—about the charging system basics of a 2002 or other vintage car. To summarize, the resting voltage of the battery (what it reads with the engine off) should be about 12.6 volts. With each 0.2 volt drop, the battery loses about 20% of its cranking capacity, so by the time it’s down to 11.5 volts, it’s typically discharged too deeply to turn the engine over. But with the engine running, the voltage at the battery should raise by about a volt to a volt and a half—it should come up to about 13.5 volts to about 14.2 volts—and the battery warning light on the dashboard should go out. On a car like a 50-year-old 2002, you may never see 13.5 volts, particularly if the headlights and electric fans are on, but the voltage should still increase visibly off its 12.6-volt resting reading. If it doesn’t, the battery isn’t being charged, and the car will at some point die when there’s not enough juice to fire the coil.

The thing that’s missing in that summary is the discussion of how to tell whether the problem is in the alternator or the voltage regulator. The two work as a pair, with the alternator capable of outputting about 17 volts, and the regulator rapidly turning it on and off so that the average is about 13.5 volts. This is why when the regulator fails in the open position, there’s no charging, but if it fails in the closed position, the alternator supplies 17 volts to the battery, causing the sulphuric acid inside to boil.

On a newer car with a so-called single-wire alternator (a misnomer, as it’s actually two wires), you can’t test the alternator alone because the regulator is part of the alternator’s brush-pack. It attaches to the back of the alternator with a couple of small screws or bolts. Without the brushes in place, the alternator is incomplete. The test you can do is examine and replace the (inexpensive) regulator and see what happens. If a car fails the charging system health test described above, and the problem isn’t due to corroded battery cables or a bad ground, the thing to do is unscrew the regulator and look at the brushes. You’ll often find that one or both of them is worn down to a nub. Spending $30 or $40 for a new regulator is often all that’s necessary to get the system charging again. And if that doesn’t fix it, then you buy a new or rebuilt alternator and keep the brush pack as a spare.

But on a car like a 2002 with an external regulator, you can test the alternator alone. Here’s what you do.

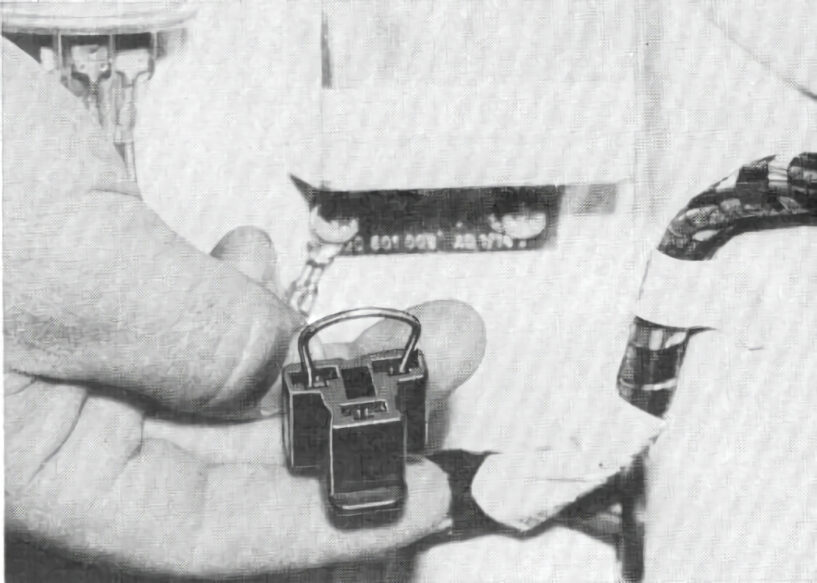

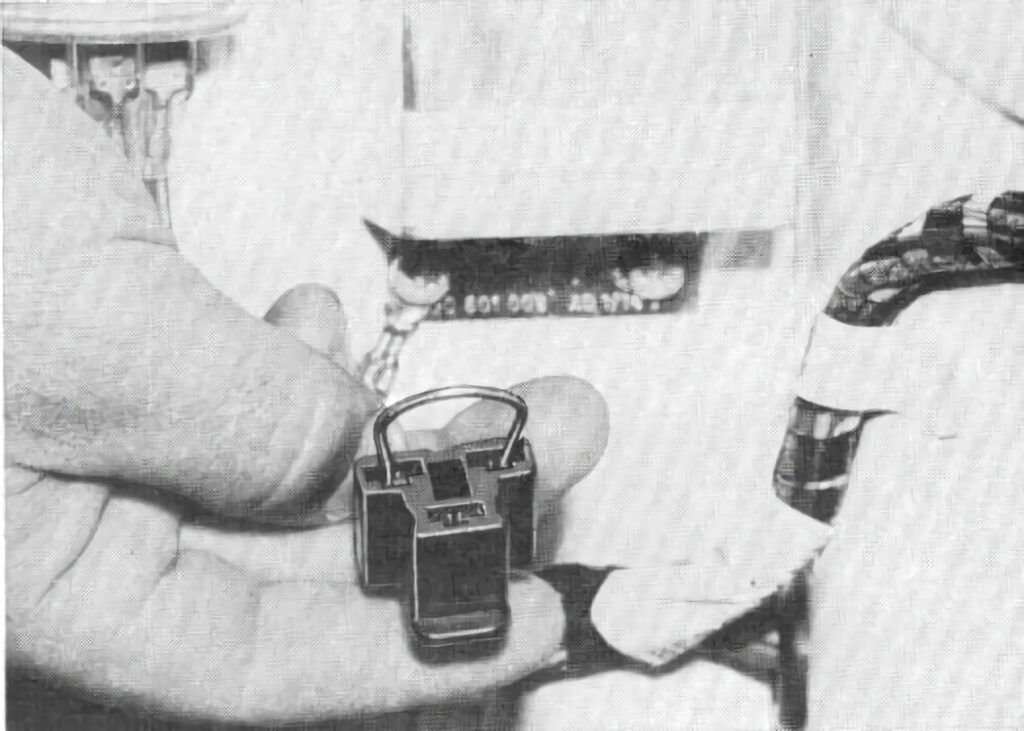

There’s a three-pronged plug in both the back of the alternator and the bottom of the regulator. Thus, the charging system design has the inherent unreliability of having nine things (the three wires connecting the two plugs, and the three push-on connectors at each end) that can go wrong. However, it’s what allows you to do this test.

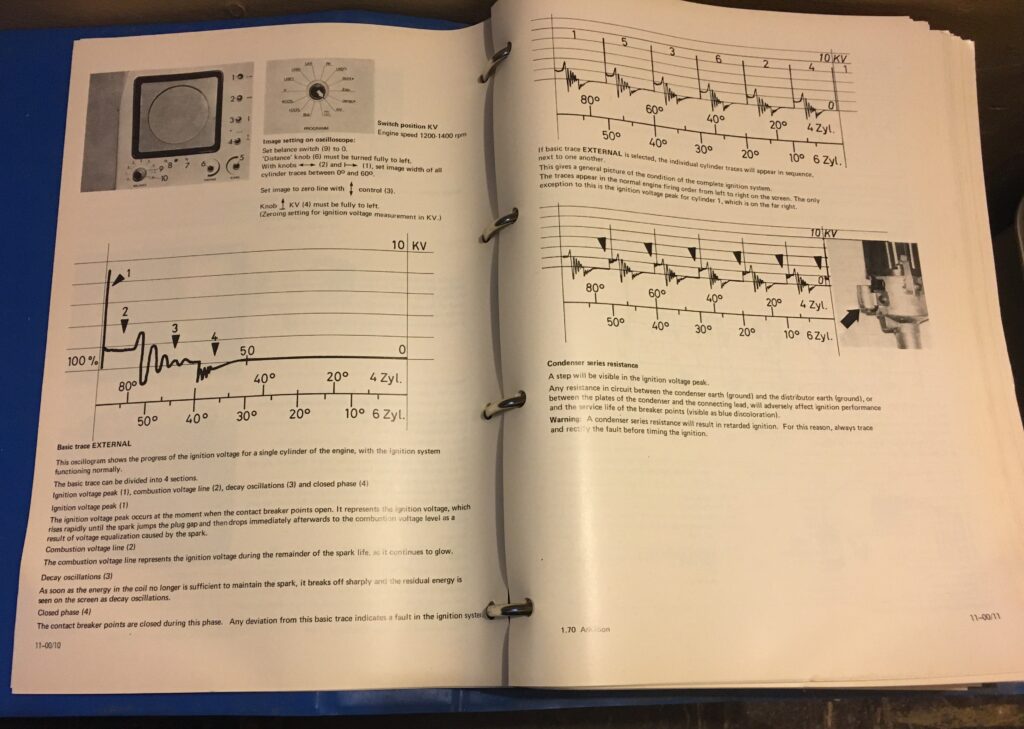

Verify that the three-pronged plug is securely in place the back of the alternator, that none of the three push-on connectors are being pushed out the back of the plug, and that there are no broken wires on the back of the plug. Unplug the plug that goes into the bottom of the voltage regulator and verify that the same is true of it. Then verify that that the big stud and nut with the thick wire on the back of the alternator is receiving 12 volts from the battery, and that the case of the alternator is grounded. Start the car and put a multimeter set to read DC voltage across the battery terminals. Then take a short piece of wire and use it to momentarily jump across the DF and D- terminals in the plug you removed from the regulator. These are the top two horizontal slots in the plug as shown in the photo below. This is known as “full-fielding the alternator.” If, when you do this, the voltage reading on the multimeter climbs from 12.6 toward 17 volts, then the alternator is capable of outputting charging voltage, and the problem almost certainly lies in the voltage regulator not doing its rapid on-off thing.

The incredibly-valuable diagram from the factory manual about how to jumper the regulator plug to test the alternator. (image courtesy of BMW)

So when you do this test, if the voltage level climbs, the alternator is capable of outputting charging voltage, and thus the problem is likely in the regulator. In addition to seeing the voltage level on the multimeter rise, you’ll also probably hear the engine note change as the mechanical resistance from the now-charging alternator loads the engine down. But if the voltage level doesn’t rise, then the alternator itself is almost certainly bad due to blown diodes, worn brushes, broken internal wiring, or other problems.

A few cautions. Don’t do this test at all if you have any aftermarket solid-state electronics installed in the car, as the high voltage level may damage them. And only do it for a second or two.

The funny thing is that the factory manual doesn’t describe this as a test to “full-field the alternator.” It just tells you to to do the test and see if it makes the battery warning light on the dashboard go out. So while the test is a little nugget of gold, its context is incorrectly represented.

So there. The factory manual is good for something. Now if only it would tell you how to retrofit a two-wire alternator. Or modify the original dealer-installed a/c system to blow cold. Or offer an opinion on progressive-rate springs. Or advise whether Bilstein HDs or Sport shocks and struts are better for a street car. Or tell you how to get a 22mm sway bar into the nose without bending any sheet metal. Or…

—Rob Siegel

____________________________________

Rob’s newest book, The Best of The Hack Mechanic, is available here on Amazon, as are his seven other books. Signed copies can be ordered directly from Rob here.

Tags: alternator test vintage manual