Chassis fabrication aside, an engine swap is probably the most ambitious undertaking that many of us vintage BMW owners will dream of doing on our cars. The allure is easy to see—wouldn’t it be great to combine dynamics of our chosen chassis with the preferred character of a revvier, torquier, or better-sounding motor? After all, you can do it with a click of a button in Forza Motorsport—how hard could it be?

It’s a topic I thought about with my oft-discussed (and optimistically-badged) BMW 635CSi, which is currently powered by a 3.4-liter M30B34 six-cylinder that made (allegedly) 182 horsepower when it left Dingolfing in late 1985, and which probably churns out 160 today, if the Bosch Motronic fuel injection decides to cooperate.

It’s not a bad motor. The M30 “Big Six” was used in one form or another from 2.8-liter variant in the E9 coupe to the 3.5-liter M30B35 used in the E34-generation 535i, and in that time it established a reputation for reliable grand-touring power. But the M30’s adequacy doesn’t mean you can’t dream of another engine, especially after seeing cars like Paul Muskopf’s V12-powered E28 5 Series at the Vintage, plenty of turbocharged S52 six-cylinder builds online (with engines borrowed from the E36 M3), or even Riley Stair’s M60 V8-powered E24 that sold on Bring a Trailer for $27,000. All of these creations have a character distinct from my plain old 635CSi, easily discernible from hearing them run or witnessing their engineering first-hand at shows.

Each has pros and cons. There’s the traditional S52, a 240-horsepower engine out of the 1996–1999 U.S.-spec M3, a practical and affordable (relatively-speaking) option, being a straight six of similar displacement with intoxicating induction noise. There are also gorgeous builds like Riley Stair’s M60-powered 635CSi, which looks as if BMW had built the car from the factory with a V8. On the other end of the spectrum are cars like Paul Muskopf’s V12-powered E28 that you may have seen at the Vintage, made possible thanks to plenty of clever cutting and steering-box wizardry to get an M70 to even fit in the E28’s compact engine bay.

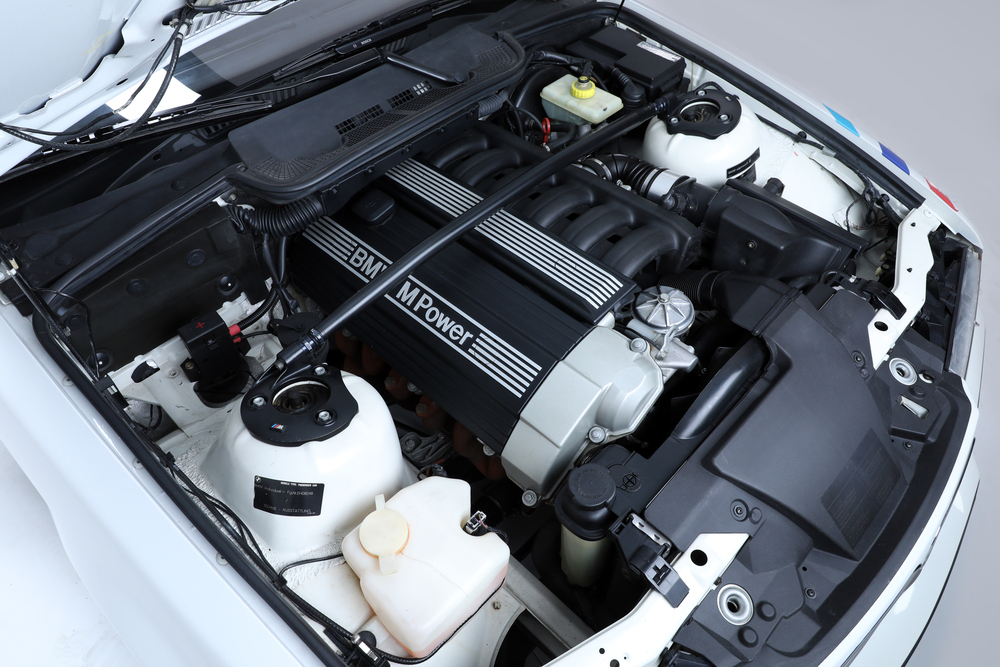

The BMW S50 in its original application—under the hood of an E36 M3 (in this case an LTW).

Whether intended for fun or for daily use, all of these builds require an immense investment of time, money, and brainpower. At minimum, they necessitate bravery and a Sawzall, and more commonly they demand a professional understanding of both BMW electronics and/or CAD software. A 3D printer or fully-equipped fabrication shop probably wouldn’t hurt here, either.

Even the process of dropping an S52 six-cylinder into my 635CSi—theoretically the most straightforward of these options—is no simple task. Pulling the old M30 would be a buffet of fluids, broken clips, and sheared wires, and would probably reveal damaged mounts, stuck bolts, and plenty of routes past the point of no return.

Then we get to the “new” engine, assuming it’s a known-good unit and doesn’t need a head gasket, a VANOS rebuild, or any accessories. If we’re lucky, it would fit and mount to the subframe—but the project could easily end up a wiring, cooling, or packing nightmare. There’s a reason it would cost twice the car’s value to have a professional installation of this engine.

So: The S52 E24 is a pipe dream. But there’s another engine swap that I have the intention of actually completing, when the time is right. If you’ve read my columns before, you know all about my 1979 BMW 733i, with its L-Jetronic ignition, long-out-of-production parts, and its occasional tendency to vent fluids and odors into the cabin. Nevertheless, my girlfriend and I love the car and have taken it all over New England, from dirt farm roads to sweeping mountain passes. In the back of my mind, I’ve found myself trying to plan for the future with this car. The problem is simple: Eventually, the strange early-production M30B32 in the 7 Series will become prohibitively difficult to maintain.

I’ve had plenty of ideas on the next step, from more common later-production M30s to V8s—even to the Toyota 2JZ and an automatic transmission, which would improve reliability and drivability considerably. But all of these schemes invite the same engine-swap gremlins that make the process just as cumbersome and costly as it would be in other platform.

If only there was a motor that didn’t need a parts store’s worth of fluids and mounts for a 40-horsepower gain; a motor that didn’t need a maze of fuel lines, pumps, filters, and pressure regulators just to idle, and had no fuel injection systems to worry about; a motor that would not only change the character of the drivetrain, but bring out the true character of the car.

Yes, I anticipate my E23 of the future will eventually be electric.

Don’t roll your eyes just yet. I’ve spent many late nights thinking about what this car will look like in twenty years, and it has become increasingly obvious that an electric motor is the one option that solves most of my problems at once. For one thing, the math works. The 733i is far from our daily driver—we use it for the occasional 50-mile afternoon drive in summer, and sometimes a 200-mile tour around Vermont, so interstate range is not a priority. And while the Sieben is a beautiful car, it’s no performance sedan. Part of this is the fault of the three-speed automatic, but the car is also heavy, with robust suspension to match—making it, accidentally, a perfect candidate for the heavy batteries that an electric conversion would require.

The common wisdom of EV conversions focuses on Volkswagens, Porsches, and other simple classic cars, but I would contest that full-size luxury cars, like the E23 7 Series or the Mercedes-Benz R107 SL, are actually the perfect candidates for heavy EV conversion. Besides spatial and structural advantages (hello, suspension travel), no one in the current decade is buying an E23 7 Series to write home about handling, blistering acceleration, or engine note.

Sure, the electric powertrain from a certain high-torque electric American luxury sedan would up the Seven’s performance considerably, but my attraction is far more practical. I may have to hand in my BMW tinkerer card for saying this, but I actually don’t want to be monitoring five types of fluids and a dozen gaskets on my sixth and oldest car, just to cruise gently around New England. For my purposes, an electrified Seven, with one moving part and a suite of stand-alone accessories, would be the perfect late-evening cruiser, never again leaving me in the dirt, soaking up gasoline in a nice autumn sweater.

As for the cost? Well, it’s not going to be as cheap as that S52—or an entire E36 M3, for that matter. But as more manufacturers dive into stand-alone EV technology, the parts bin becomes deeper. Tesla drive axles and batteries, for instance, can already be implemented in vintage cars thanks to kits like this available online, and the options will only increase as time goes on.

As for the purists: Electrified Seven or not, I’ll still need my fix, Red Barchetta-style, of unburned hydrocarbons, manual transmissions, and loud exhausts, so the E24 is here to stay—more than likely with its factory M30 straight six. The future may have arrived, but some things never change.—David Rose

[Photos by Tucker Beatty, EAG, and David Rose.]