I like driving in the American West. I like the vistas, and seeing a hill ahead that you won’t reach for many minutes. At night, the lights of approaching towns are visible from twenty miles out. I enjoy that you can watch a storm coming from far, far away, towering clouds laced into the perspective of the foreground and horizon, and thus get a sense of how big it actually is. I like that the storm—despite your having time to anticipate its arrival—can still put you in awe of its power.

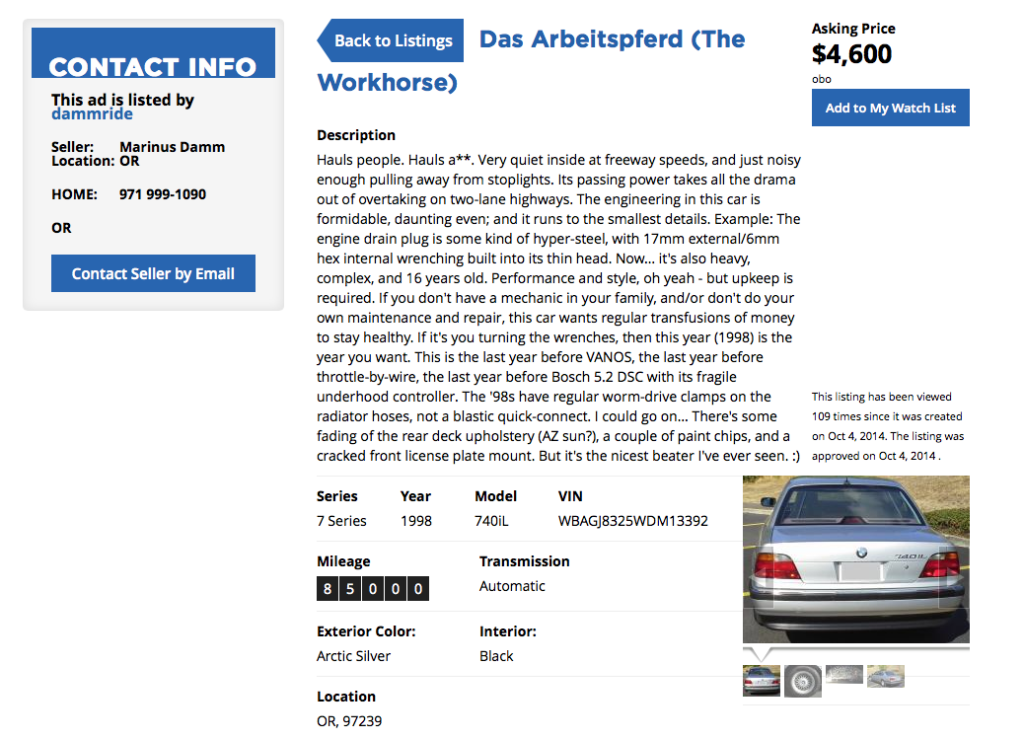

I like the classic lines of the 740iL.

For a long time I’d been immune to the E38 7 Series’ charms. Then, at a BMC ACA gathering at the race track in Portland, I was strolling around the corral appreciating the early M5s and 2002s. Over by the new M3 lounged a lonnnnng dark green 740iL. I didn’t recognize what it was; I’d never paid attention to the 7 Series.

But there, on the grass next to the newer cars, the Seven was completely at home. The styling is dignified, taut and crisp, demurely displaying its classic proportions and classic lines. That green car was a 2001, the final year of the E38.

My interest aroused, I started reading up on them.

The E38 was sold in the U.S. beginning in 1995, anticipating the E39 5 Series by a year. To my eye, it’s still the best-looking of the large-barge class: unmistakable as a BMW, and unmistakably royal, but in “Yes, I spent two tours with the Fusileers in the Middle East” royal. It looks the part of a professional, not a dilettante.

If you are charmed by the E38’s style (as I was), you might seek an example from the last production year, 2001, thus enjoying all the fixes and improvements incorporated during the model’s run. There are plenty of 2001 Sevens available, because it sold boldly and well. Wikipedia’s article claims that 2001 saw a sales spike as the next-gen “Bangle Butt” E65 7 Series appeared. And my normal modus operandi is to take the final edition.

See, I’ve worked in manufacturing, I know the drill: Fix it on the production line, and you won’t have to fix it at the dealership under warranty. This approach is manifestly cheaper, not to mention preserving of the firm’s reputation. As failings are detected in the delivered product, fixes flow into the line for the upcoming units. So the final year of a model is generally the best year.

In the case of the E38’s six-year run, a life-cycle impulse (LCI) (aka facelift) came in late 1998. The external changes were slight: Its front and rear faces shifted slightly, and revised headlight and taillight forms followed. These changes did not detract from its handsomeness, nor its presence. But in the chassis, drivetrain, and cabin, the next wave of technology arrived. The throttle cable disappeared; drive-by-wire was the new buzzword. The M62 V8 got variable camshaft timing, controlled by the ECU (VANOS). Torque was slightly up, fuel consumption was slightly down. The navigation screen grew. More components had their data communications routed through the main instrument cluster (sorry: did you say through the main instrument cluster? Yes.). The ABS and traction control leveled up, too. The Future Is Now.

Alas, that Now is ever-changing, and some promising shoots off a hardy shrub don’t pan out. While all those facelift-introduced improvements were startling and wonderful in the Clinton era, the advanced technology has proven a bit fragile in service. What these advances represent, twenty years on, is not so special and admirable today. The state of the art moves on; even the most minor new BMW surpasses the techno-level of a facelifted E38.

What lingers is the trouble that these complex systems pose for the amateur mechanic. VANOS units (or at least the seals) wear out, and get rattly. The multi-channel ABS module in the LCI cars has sixteen very, very, VERY fine gold wires, and the underhood heat slowly but certainly cooks those wires. I could go on.

This is why, although many people revere the last three model years, and I’d normally be among them, in this case I prefer the last year of the pre-facelift cars: 1998. No VANOS. No multi-channel ABS, no drive-by-wire, no a-dozen-other-things-that-were-magnificent-then-but-are-primitive-now.

I wanted a 1998. If you do, too, be aware that the LCI was a mid-year change; the difference in manufacturing dates between pre- and post-LCI cars is small. Make sure that your E38 is on the right side of that line.

Before I bought my 7 Series, it had spent time in Arizona; the faded rear deck upholstery spoke to being parked outside in the desert sun. But its body and mechanicals were mostly solid. I paid an independent BMW repair shop to correct a small coolant leak, and then took to driving it as my primary car. Almost fully depreciated, it could be parked on the street without worry. It had sufficient passing power (and braking prowess, and cornering aptitude, etc., etc.). It had a level of driver and passenger space that reached—and surpassed—my needs. The Seven was an eye-opener; I’m certain that the X5 diesel is in my driveway because it mimics the room for my gangly (chonky!?) self that the E38 provided.

On the freeway, miles passed almost without notice. The car was quiet inside, even at high speed. It never felt ungainly, and surely never felt slow on the road. I drove from Salt Lake City to Portland in a single bound, and arrived relaxed and fresh. I ran it in a Saturday-morning rally with a novice timekeeper along; we left a rest stop ten minutes late, so we had to hustle through hilly curves along the Willamette River. No problem, said the Arctic Silver sled, drive as hard as you wish, sir.

We erased our time deficit before the next control.

I miss that car. It was a workhorse: steady, strong, and enduring. Two things doomed it: first, the smaller part. It inspired spontaneous and demonstrative hatred from some of the bicyclists in Portland. I’m not sure that I—myself a bicyclist—blame them; the aura of the car was unmistakable. It spoke of authority, affluence, and an assertion of privilege drawn from ancestry. It was practically a monument to cutthroat capitalism.

Being a doubter of most isms, I could only weakly defend the merits of the machine as a machine, while asking the objectors to gloss over its socio-economic statement. Some will say, “Just ignore the haters”—good advice always, but sometimes the core of truth in the protest can’t be dismissed so easily. On the other hand, many car people admired the 740iL; but those worthies also admired our Rebel Blue Volvo C30, and that runabout did not trigger the negative reactions that the Seven did. “Why rub anybody’s face in it?” I thought.

I put an ad in Roundel, but it brought only one person to my door—and he was really a fan of big Mercedes-Benz, so the hook didn’t set.

I put a For Sale ad in Roundel.

The second thing source of doom: I put the car to work on the Bonneville Salt Flats.

That’s a custom butcher-block pushbar on the 740iL.

The Flying Pickle is towed by SeaRay.

O, wretched place! It can beguile the visitor with peace and innocence, as it did in 2013. The salt was dry, and mere specks of salt flew up from the wheels into the bodywork that year. It was a minor event to clean up. So the Seven and I returned the following year: Ewww. This time the salt was clammy, cloying, clinging, corrupting. It got everywhere: into all the body seams and all the underneath electrical connections.

Two ABS sensors failed on the way home. The super-high-tech thin-head oil-drain plug sloughed off tiny slivers of rusted German steel alloy like a cheese block being diced by a cleaver-wielding speed freak. The lights on the dash flashed, not so much a dit-dit-dah-dit as a Close Encounters Of The Third Kind melody beat.

The engine/trans/brakes/steering were fine, it was the electronic parts that became temperamental. This time the For Sale ad ran locally, and carried warnings and cautions aplenty. Nevertheless, a couple showed up, drunk as skunks, chauffeured by their sober son. Somebody in the family had just come into some money, and they were determined to buy a luxury car. One short cruise with them in the back seat was all it took.

I’d buy another one, perhaps a dark green color this time, a bit less ostentatious. Still a pre-LCI edition, I think. Hey, didn’t BMW put the twinned-M20 V12 in some of those? Now, that’s a car. I promise that I will not take it to Bonneville, Scout’s Honor.—Marinus Damm

[Photos courtesy Marinus Damm.]