There’s an episode of the animated TV show Archer where Sterling Archer is stranded in a freight-train boxcar with his mother’s Cadillac-salesman boyfriend Ron, who, surprisingly, has a briefcase full of cash. It turns out that Ron is a far more interesting character than he initially appears to be; during a recitation of his backstory to Archer, he explains that before he sold cars, he used to steal them, and his team got arrested and jailed. He was the only one who got away. The cash, he says, is “the least I can do to back them pay for all the years they lost. Plus, most of it is from charging poor saps for that frickin’ undercoat.” He looks at Archer and says, with the dead seriousness of someone who has the inside scoop, “Never… get… the undercoating!”

Perhaps at some point I’ll do a detailed piece about my experiences with rust protection, but for now, suffice it to say that when you find aftermarket undercoating on a vintage car, it’s usually not a good thing. The worst is that truck bedliner-like stuff that you often find sprayed with a fire hose on the undercarriage; it not only hides what’s underneath, but if there’s rust there, it allows it to fester. In my opinion, if you have to undercoat, the oily or waxy stuff is much better.

But here’s the problem: In terms of a vintage car’s value, undercoating is an oddly self-defeating thing, because even if it was properly applied, and was successful in keeping rust off a car over the decades, when it comes time to sell the car and properly present it in the marketplace, the presence of blatantly visible undercoating, even if it’s waxy and effective, is generally not desired.

Such is the case with Hampton, the 48,000-mile ’73 2002 I bought in September from its original owner. During the purchase negotiation, part of the disconnect with the seller was that she regarded the car as in “excellent condition,” and had images of top money on Bring a Trailer. While the interior is as mint as you’ll find in an unrestored 2002, the body virtually rust-free, and the Chamonix white exterior quite good except for a bunch of dings, the car had been dead in storage for a decade, and the engine compartment didn’t match the condition of the rest of the car; it looked like that of any other tired old BMW.

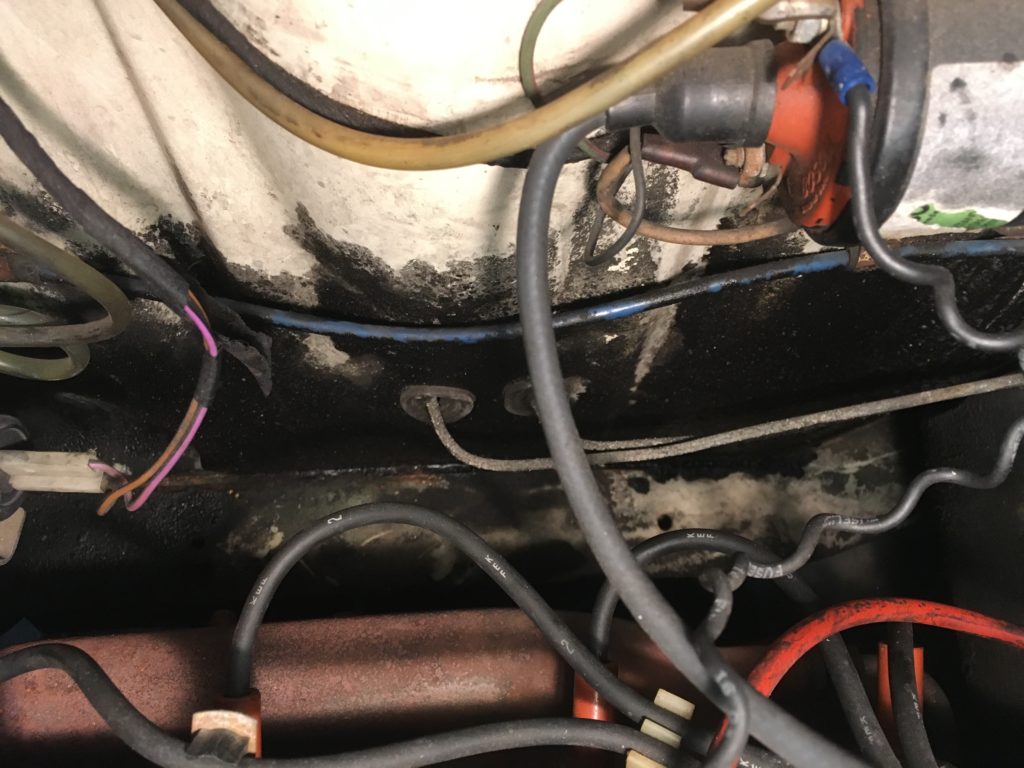

Worse, I could see some sort of black stuff sprayed inside the nose, behind the headlights, along both sides of the engine compartment, and under the wiper cowl. Initially I wasn’t sure whether it was primer, undercoating, bedliner, or something else. I explained to the seller that the cars that bring all the money at auction are the ones that present themselves as a unified whole, and that anyone interested in this one would immediately see the black stuff, wonder if the car had been in a front-end collision and been slap-dashed back together, and the image of the car as a one-owner unmolested survivor would crumble. In order to maximize the value of the car, the black stuff—at least the portions that were plainly visible—had to come off. Whether that was even possible to do in a cost-effective fashion, I didn’t know.

In addition to the generally shabby engine compartment, my eye was immediately drawn to the black whatever-it-was behind the headlights, as anyone’s would be. You can also see the black goo peeking out from the hood hinges.

During the fall, after doing some light sorting out to bring the car to the point of reliable drivability, I began examining the black stuff. It did seem to be waxy undercoating. When I looked, I found the plastic plugs along the fender wall where the stuff was sprayed in. But man, whoever laid it on did so with reckless abandon, because it wasn’t just sprayed into holes that were then plugged; the stuff was absolutely everywhere. And because the car was white, it stuck out like mold on a white plaster wall.

The smoking, uh, plug.

I began by addressing what my eyes were most drawn to: the black goo on the small flat horizontal sections behind the headlights. I first tried scraping it off with a plastic ice scraper. That had very little effect. I switched briefly to a single-edged razor blade. This was very efficient when wielded at precisely the right angle (and seemed reasonable, at least to me, since I was attacking a small dead-flat surface under the hood), but once I felt it catch on the metal and paint, I winced and stopped.

I called my friend Paul Wegweiser, who has done body restorations on some very high-dollar cars, and asked for his advice. Paul recommended a family of products generally known as grease, wax, and tar removers. I did some reading on Amazon, ordered a spray bottle of Kleanstrip Prep-All, and went to town. The going was very slow, but with me working with the Prep-All and using copious quantities of paper towels, the waxy undercoating slowly came off. Check out the transformation between the two photos below:

Before…

…and after.

Unfortunately, this is just the low-hanging fruit. Trying to get all of it off the headlight buckets themselves will be murder. And, as I said, the undercoating is also deep down both the left and right engine compartment walls and along the sides and bottom of the nose near the radiator.

My back is going to feel it when I try to clean THAT.

At some point, I’m going to need to bite the bullet, go all-in, and do some serious disassembly. But, hey: It’s a long, cold winter ahead. At least it’s a never-ending answer to the question, “If I grab a hot cup of coffee and go into the garage, what could I work on for the next ten minutes until both it and I get cold?”

And when it’s finally all off, and someone hands me a suitcase full of money for the car, I can look at them and say, with the dead seriousness of someone who has the inside scoop, “Never… get… the undercoating!“—Rob Siegel

Rob’s new book, Resurrecting Bertha: Buying Back Our Wedding Car After 26 Years In Storage, was just released and is available on Amazon here. His other books, including his recent Just Needs a Recharge: The Hack MechanicTM Guide to Vintage Air Conditioning, are available here on Amazon. Or you can order personally-inscribed copies of all of his books through Rob’s website: www.robsiegel.com.