A few weeks ago, as I was closing in on getting the Lama (the worse-than-expected 535i I’d bought sight-unseen and had shipped from Tampa) up and running after its decapitation and valve job, my friend Andrew Wilson began using the word “Lamathrust” on my Facebook page. Sometimes it was just the single word with an exclamation point. Sometimes it was things like “Sulu, engage the Lamathrusters!” It was pretty funny, but there was something about it I wasn’t understanding, like those cat-related “I Can Has Cheezburgers” memes that were all the rage a few years back.

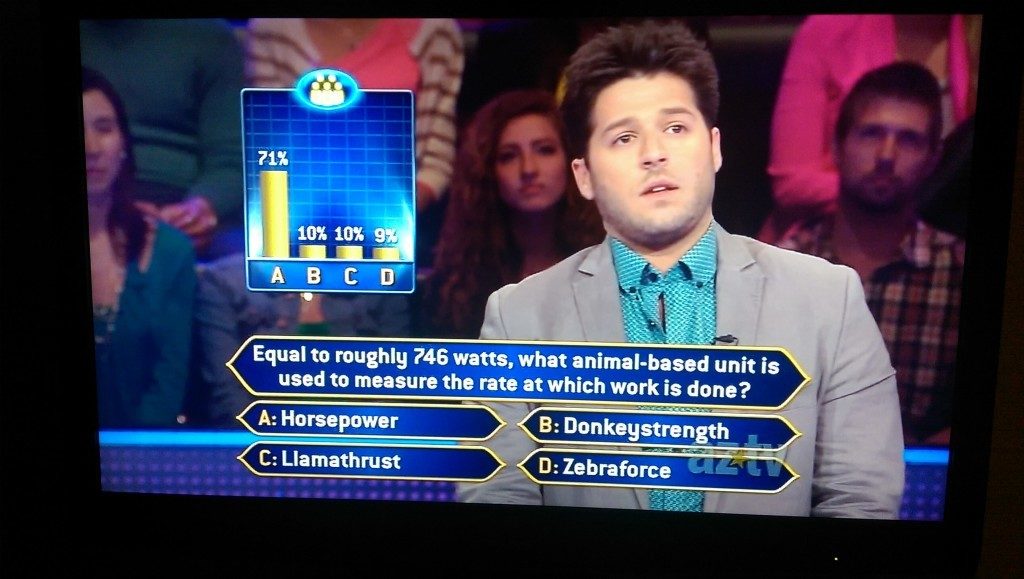

It turns out that ground zero of “llamathrust” (I’m switching from BMW interior color-referenced spelling to mammal-referenced spelling) is a December 2014 episode of the show “Who Wants to Be a Millionaire” during which a contestant was asked the question “Equal to roughly 746 watts, what animal-based unit is used to measure the rate at which work is done?” The choices were:

a) Horsepower

b) Donkeystrength

c) Llamathrust

d) Zebraforce

As you can see from the Snopes-verified photo below, I’m not making this up.

The origin of llamathrust.

Pretty easy, right? However, the contestant was rattled, and asked the audience for their advice. He reportedly leaned toward “donkeystrength” before heeding their hollers and correctly choosing “horsepower.” A pity, really. Had he actually chosen “llamathrust,” he would’ve gone down in history as more of a legend than he already is. If you google “llamathrust,” you’ll find many references to the event, memes generated around it, llamathrust-related merchandise, conversations about the state of education in American, and a predictable off-color alternate definition in urbandictionary.com.

In the days that followed my introduction to Lamathrust, I found that I was beginning to use the phrase “achieving Lamathrust” around the house as a synonym for the as-yet-unfulfilled act of driving the resurrected Lama. The car’s punch list wasn’t all that long, but certain issues seemed to drag on, and Lamathrust was surprisingly elusive.

One issue was the instrument cluster. None of the gauges were working, and especially considering that I didn’t know why the head had been warped seven thousandths of an inch, I really wanted to have a working temperature gauge when I drove the car. On 1980s-era BMWs, it’s common to have to pull the cluster, remove the Service Indicator (SI board), and replace the soldered-in batteries. I de-soldered the Nicads on the board and soldered in new ones I’d bought, but the board still didn’t work. It turned out that, as commonly happens, the Nicads had leaked, which corroded and probably ruined the board.

You can see the corrosion on the right side, underneath the removed Nicad battery.

I posted about the problem on myE28.com, and certified nice guy Aaron Manderbach contacted me, saying he had a spare board, and would be in my neighborhood in a few days. We met at a brew pub, and in exchange for a signed book and a paid bar tab, I left with a later-style SI board with lithium batteries instead of the leak-prone Nicads. The lithiums, however, still needed to be replaced.

My soldering skills are fine when I’m dealing with isolated components, but I’m uncomfortable soldering things on something like the SI board which is two-sided, has a waxy coating that has to first be scraped off, and where traces run very close to the thing I need to solder. I decided that it would be easier to leave the battery tabs soldered in place on the board, and instead, pop off the tiny spot welds that hold the tabs to the battery terminals, and solder the tabs to new batteries. This is certainly possible, and there are dozens of videos on soldering wires directly to battery terminals, but despite purchasing a high-temperature soldering iron, I had trouble getting solder to flow over the terminals of the replacement batteries. In the end, I was successful at soldering new batteries to the original tabs, but it wasn’t pretty, and if I had to do it again, I’d opt for buying the batteries with the tabs already attached, and carefully soldering them to the board.

Popping these spot welds and soldering new lithium batteries to the existing tabs as I did is not something I’d recommend.

While I don’t apologize for my money-saving ways (I will nearly always default to the least-expensive path), my multiple attempts at resurrecting the instrument cluster as cheaply as possible had caused me to throw money at the problem a handful at a time. I had a disassembled instrument cluster on the table for nearly a month, and it reached the point where the lack of the cluster (and with it, a working temperature gauge) was the gating function for driving the car.

Fortunately, after what I thought was a botched soldering job on the lithium batteries, when I buttoned up the cluster and put it in the car, the gauges all actually worked. A minor annoyance was that the inspection and service indicator lights were on. I swore that I still had the old Peake tool to reset them, but when I located it, mine was for a 20-pin connector, and the car had the 15-pin version. However, it wasn’t hard reacquaint myself with the procedure of jumping pins 1 and 7 on the connector. I had to smile when the service lights went out.

Completion is good!

With the cluster in place, I started the car and let it warm up. The temperature gauge now moved, but seemed to languish near the bottom. It jumped to the right when I grounded the sender’s wire, indicating the problem was with the sender. I replaced the sender, and the gauge finally showed reasonable readings. With that, I took the Lama for a few careful (and illegal; the car is insured but not yet registered) spins around the block.

The first thing I noticed was, to no one’s great surprise, how much quieter the car was and how much better it ran now that it was running on all six cylinders and had crisply-closing valves as opposed to when it had a broken rocker arm, three bent intake valves, and several valves that, as the machinist said, “must’ve been sealing on carbon.” After all that work replacing the head, this was so satisfying that, even though my foot was light and the speeds were less than 30 mph, it almost qualified as Lamathrust.

The oil burning when the car was first delivered appeared to be gone.

The second thing was that, to my delight, the car’s oil burning seemed to lessen as I drove it. When the car was initially delivered and backed off the trailer, it was literally surrounded by a cloud of oil smoke, the first of several “what did I just buy” moments (the pièce de résistance was, of course, finding the broken rocker arm). This kind of oil burning isn’t at all unusual in a car that’s sat for five years. However, it could be due to rings stuck to the pistons from lack of use, or from oil squirted down the plug holes to lubricate the engine after its long snooze, or from the rings, lands, and cylinder walls simply being shot. You don’t know which, and really, you just need to drive the car to find out if the burning is going to lessen. It didn’t lessen much when I ran it around the block several times before pulling the head, so there definitely was the boogieman in the closet that, after doing all that work to pull the head, disassemble it, have the valve job done, and reassemble and reinstall it, the car might still be a burner. So the fact that, in just a few miles of around-the-block running, the exhaust appeared oil-free was a major relief.

But the third thing I noticed was the unresolved braking issue. As I’d mentioned in an earlier piece, when I bought the car, the brake pedal went to the floor. In trying to bleed the brakes, I’d found that I was getting no fluid out of three of the four calipers. Before I pulled the head off, I’d replaced all of the original rubber flexible lines with braided stainless ones, but to my surprise, I still got no fluid out of the left front caliper. I’d traced the problem and found that fluid for that caliper was entering but not leaving the ABS module. I’d followed instructions on myE28.com on how to jump across the pins on the ECU connector to actuate the ABS pump and cycle the control valves, but it made no difference. This had left the brake pedal still clearly feeling like the system had air in the line. I thought that, if the problem didn’t resolve itself, I might have to remove the ABS module, open it up, and look for a blockage.

Over the next week, as I dealt with some other issues, I made it a point to run the Lama around the block a few times each day and stomp hard on the brakes. At the end of the week, I again bled the brakes, and this time was successful at getting fluid out of the formerly recalcitrant left front caliper. The pedal finally felt nice and hard. I drove the car again. While it still has the same rotors and pads that it had been wearing for the five years it was in storage, nothing felt amiss in the braking any longer.

That left mainly just a few inspection issues. When I first drove the car, both the low and high beams turned on and stayed on as soon as the ignition was cracked, as if the flasher circuit in the stalk was stuck on. Repeated exercise of the stalk appeared to un-stick it. I stepped through the rear lights and got most of them working through a process of identifying bad bulbs and cleaning the contacts on the housings. The hold-out was the reverse lamps. I mentioned this to Aaron Manderbach who supplied me the SI board. He advised that the reverse lamp switch on the side of the transmission is a part that dies. Normally I’d test something like this to make sure it’s bad before buying a new one, but for fifteen bucks, a cheap and easy plan was to jack up and crawl under the car, swap the switch, and see what happens. I grinned a first time when I tested the just-removed old switch and found that it was bad, then a second time when I put the car in reverse and saw the lamps come on.

The reverse lamp switch was easy to replace.

Suddenly, I had a running, driving, inspectable Lama.

So then came the choice: Do I spend the money to legalize the car (which, between registration, title, sales tax, and inspection, would run about $330)? The legality would allow me to drive the car further and faster, which would both aid in the sort-out as well as enable winter storage of the car 50 miles away in my storage spaces in Fitchburg. Or, do I stop testing it and instead sell it unregistered and as-is? This would lower the value of the car (no one likes being restricted to around-the-block test drives), but it can sometimes result in a quick sale to a buyer who is looking for a value-priced project and isn’t afraid of an untested car. I tried what I did with the Black Shark I sold this spring—floating it on Facebook. The response was very positive, but no one threw money at me. So, by the time you read this, I should have a legal Lama.

However, I reached a point where couldn’t stand it any longer. Drawing comfort from the fact that the car is, in fact, insured (I put it on my Hagerty policy before it was shipped), I slapped on the plate from one of the other cars, grabbed the bill of sale, the old title, and the Massaschusetts RMV1 form from Hagerty (this doesn’t really protect you unless the paperwork is dated within the past seven days, but it at least gives you a plausible story that you just bought the car and are operating within the seven-day window), and took the car for a longer spin. When I hit my favorite entrance ramp—the one I nailed Bertha on this summer—I found myself channeling my friend Andrew and saying, in full Dr. Lizardo voice from The Adventures of Buckaroo Bonzai, “Mister Big Boo-TAY: Engage… LAMATHRUSTERS!!” (The video can be seen here).

In the meantime, I can’t get enough of looking at llamathrust-related paraphernalia. If only they sold it with the proper number of L’s.

One L or two, you know you want it.

—Rob Siegel

Rob’s new book, Just Needs a Recharge: The Hack MechanicTM Guide to Vintage Air Conditioning, is available here on Amazon. His previous book Ran When Parked is available here. Or you can order personally inscribed copies of all of his books through Rob’s website: www.robsiegel.com.