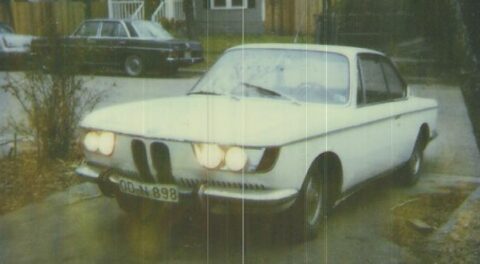

Two weeks ago, I described the work I did on Bertha during the feverish weekend just before Oktoberfest. I’d gotten Bertha’s head back from the machine shop, assembled and installed it, and, like some automotive Don Quixote, madly attempted to fight my way through a myriad of issues to reach the point where I could drive the car and make some sort of rational decision on whether she was fit to drive to Pittsburgh.

This was, of course, lunacy, and I knew it; no dead-for-26-years car is going to be ready for a 1,200-mile round trip after just a few runs around the block.

As it happened, I didn’t even meet that easy-sounding but meaningless around-the-block goal, because when I drove Bertha out of the garage and up to the top of the driveway, her whole vibe was, “Don’t even think about it, pal.”

I was reacting to a few specific things. The dual Webers hadn’t been balanced yet, so there was a fair amount of roughness and engine vibration at idle. And the tires—three Yokohama A008s that dated back to Ronald Reagan’s second term and one Michelin XAS that likely knew Gerald Ford—were so bad that I swear I could hear them plotting to kill me during the 50-foot run up my driveway.

Would YOU drive on these much farther than up the driveway? No? I didn’t think so.

But the thing I most reacted to was the feel of the pedals. The clutch hydraulics—the master and slave cylinders—had not yet been replaced. These are components that, after sitting for 26 years, will go bad, as evidenced by my adventure with Louie eighteen months ago, when I changed the clutch slave but not the master, only to have the master let go as I was about to get on the entrance ramp and embark on the long drive home.

Bertha’s brake pedal felt a bit crunchy and granular. I’d changed all of the brake hydraulics except for the brake master cylinder, and I imagined that the granularity I was feeling was the master grinding up and spitting out its atrophied internal seals.

The worst was the accelerator pedal. Well, no: Actually, the pedal itself was missing, since the section of floor with the two metal posts holding the pedal in place had rotted away. Although I had freed the seized rod that goes through the pedal bucket and installed a stiff spring that pulled the throttles closed, something was still wrong with the accelerator linkage. I would pull up on the linkage to close the throttles and the car would idle at about 1,000 rpm, but after I’d tap the gas, the throttles wouldn’t fully close, and linkage would settle with the rpm at around 2,200.

Having had accelerators stick open twice, once in my 3.0CSi at Lime Rock at the end of the main straight and once in my 635CSi on a public road, I’m very sensitive to even the possibility of it happening again. More than anything, this was where the “Don’t even think about it” vibe was coming from.

I replaced the accelerator lever arm that I’d stripped and jury-rigged last month.

So when I got back from Oktoberfest—Kugel was kind enough to carry me there and back—the first thing I did was deal with Bertha’s accelerator-linkage issue. I found that the sticking was simply due to the long linkage rod rubbing against the hose between the clutch master and slave cylinders. Before I fixed it, though, I addressed a related issue from when I’d first gotten the car running in Alex’s neighbor’s garage: While I was trying to free up the seized rod through the pedal bucket, I had stripped the splines off the lever arm that it attaches to, making it so that the linkage could slip if you mashed the pedal too quickly. A friend had sent me a new lever arm with intact splines, so now I took the opportunity to install it. I then repositioned the clutch slave hose and verified that the linkage moved freely, without binding or slipping. I started the car and revved it, and confirmed that the idle returned to its resting rate of about 1,000 rpm.

With that, I fired up Bertha and ventured gingerly forth from the end of my driveway and out onto the street.

The car was still spewing a visible cloud of oil smoke, as is quite common with engines that have sat for a long time; you need to run them and see if the rings free up and the burning lessens. As I drove the car, the main thing I noticed, aside from the feel of the laughably ancient and mismatched tires, was a lot of noise from the Getrag 245 five-speed transmission, with a strong whine that accompanied getting on and off the gas and went away when I put the clutch in or coasted in neutral. (“Layshaft bearings,” immediately commented my friend Tom Jones.)

I took the car back to the garage, put it up on the mid-rise lift, drained the transmission, and refilled it with fresh Red Line MTL. This in itself was a task, since the 17-mm Allen-head fill plug on the side of the five-speed is almost impossible to access with the transmission installed; a standard 17-mm Allen key doesn’t clear the transmission tunnel. I took my 17-mm key, cut about 3/4″ off the end to make a stubby key, slid it into the hole for the fill plug, put a wrench around it, and loosened and removed the plug.

Unfortunately, the Red Line MTL made no difference; the transmission remained noisy and whiny. Oh, well. On the plus side, I thought, it was a good thing that I didn’t buy Bertha back as a parts car with a mind to scavenge the five-speed.

This is how you use a cut-off 17-mm Allen key and a wrench to loosen the fill plug on the Getrag 245 five-speed.

The noisy five-speed notwithstanding, that first drive of maybe a few hundred feet was quite successful. I checked for fuel, coolant, and oil leaks, found none, then went for a slightly longer drive around the block. The tires warned me not to get up above 20 mph, but the car felt pretty good; the carbs were still out of balance, but the engine revved smoothly without obvious stumbling or bucking. The “granular” feeling of the brake pedal vanished with use; the source was probably in the pedal pivot itself, and not in the master cylinder. For a longer road trip, the clutch hydraulics did need to be prophylactically replaced, but they continued to function.

I thought, damn, if this car had decent tires and a valid registration, I could actually drive it—safely and legally—and see what it would REALLY do.

I want a set of beat-up E30 14×6 steelies like these. (photo by Clay Weiland)

For Bertha’s wheels and tires, I know exactly what I want. There’s a look right now that’s in vogue: heavily patinaed paint and high-dollar shiny alloys that fill up the wheel wells. That’s the exact opposite of what I want. My goal is to keep Bertha true to her heritage of 1980s period-correct 2002 modifications.

A Roundel article 30-ish years ago by Bill Howard on so-called “plus-one” conversions (changing from 13″ to 14″ wheels to shorten the tire sidewall) mentioned that people had discovered that E30 14″ bottlecap wheels bolt right onto 2002s and have the correct offset to fit without rubbing. You didn’t really see the later nicer-looking E30 basketweave wheels on 2002s until the early 1990s; in the ’80s, they were still too new and too expensive. But back in the day, E30 14×6 steel wheels were a moderately-priced addition; I almost put them on Bertha before I sold her to Alex.

They used to be available in silver. Now they only come in black. Personally, I positively loathe the look of black wheels on any car. I could buy a black set and paint them silver, but they’d look too new. What I want is a worn-in silver set that looks like it’s been on the car for 30 years, with the same patina as the rest of the car.

Until I find such a set, I took Bob Sawtelle, one of my recent traveling companions to the Vintage in Asheville, up on his offer to loan me his E30 basketweaves with good 195/60-14 rubber on them (these were left over when Bob upgraded to Panasports). I made a quick run down to Marshfield, Massachusetts, in the E39, snagged the ‘weaves and tires before Bob changed his mind, and mounted them on the car. It’s not the look I want on Bertha for the long term, but it’s exactly what I need right now. Thanks, Bob!

With Bertha wearing rubber that could safely see third gear, I simply needed to register the car.

I’d previously called Hagerty and added the car to my policy, so I already had the paperwork in my hands to take to the registry. When I added Bertha, Hagerty didn’t even raise my rates, since the incremental cost of insuring Bertha for three grand, on top of the other eight cars I have insured with Hagerty, didn’t move the needle. (I have to laugh whenever I call Hagerty and they refer to “your collection.” I don’t have a collection—and if I did, Bertha would lower rather than raise its value.)

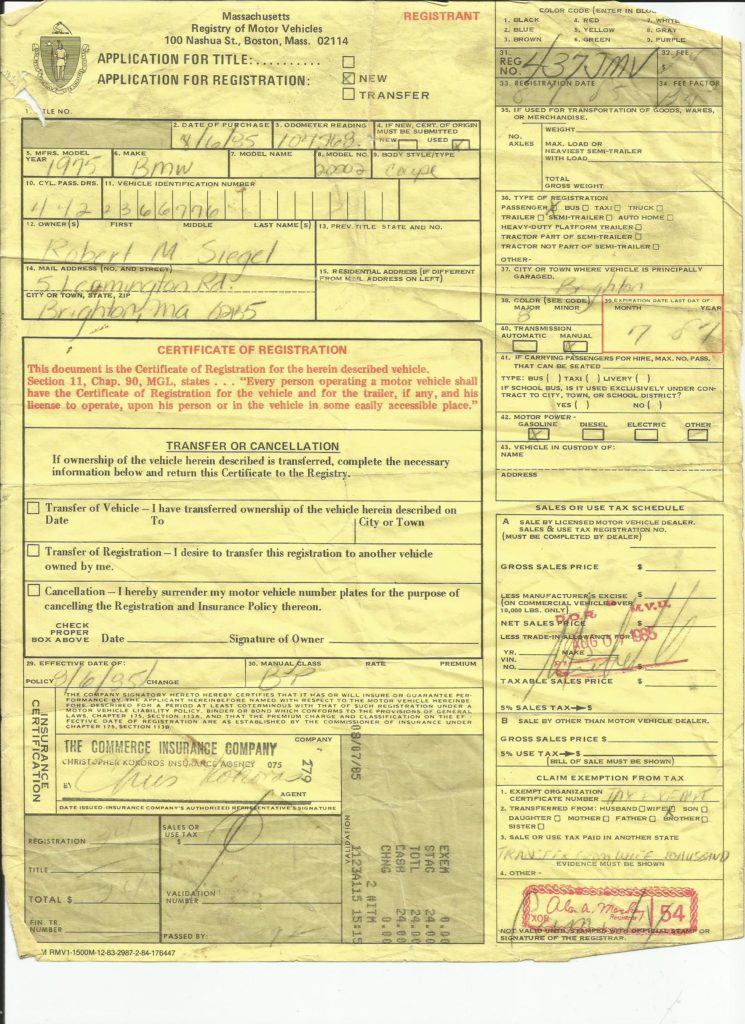

There is a kismet-like ownership issue that accompanied my re-purchase of Bertha. When I bought back the car from Alex and he searched for the title or a prior registration, he couldn’t find either; all he could produce was an old plate-return receipt, but the VIN on it wasn’t Bertha’s. After thinking about it, Alex realized that 30 years ago, he may have played fast and loose with license plates, moving one plate among several 2002s, and may in fact never have registered Bertha.

I looked in my old folder with Bertha’s paperwork and found my Massachusetts registration for the car from 1985. I slowly realized that, legally, since Alex had never registered and titled Bertha in his name, technically I had never lost possession of her.

In other words, not only had Bertha come home, from a legal standpoint she’d never left.

This was more than just a feel-good issue, because in Massachusetts, when you register a car you just bought, they assess you 6.25% sales tax, and it’s not on the basis of what you paid, but on the NADA low value of the car. For Bertha, a 1975 2002, the NADA low value is $11,300, which would normally result in a sales tax bill of $706. However, if I am still legally Bertha’s owner, I don’t have to pay the sales tax, because I’d already paid it when I’d first registered the car 33 years ago.

I took the prior registration and an old plate-return receipt from 1988, both in my name and with Bertha’s VIN on them, to the registry. After I stumped two young registry employees with this still-own-it-but-it’s-been-off-the-road-for-30-years scenario, a kindly older employee understood, and processed the paperwork in five minutes, assessing me registration and title fees, but not the $706 sales tax. (“We try to be the good guys,” he said.) You always get a great feeling when you overcome some challenging title issue and escape from the registry with a fresh license plate for a car, but this one was particularly sweet.

My 1985 registration for Bertha showed that I owned the car and had already paid sales tax on it.

That evening, with a legal plate and non-homicidal rubber on the car, I took several more restrained runs in larger and larger orbits around my house. The transmission was certainly still noisy, but I didn’t think there was any danger of imminent failure. And crucially, with Bertha still wearing her ancient water pump and radiator, she seemed happy, running right in the middle in the temperature gauge even in Boston’s 90-degree heat.

After tweaking a few things, I couldn’t stand it anymore: My right foot was just itching to mash the go pedal. I threw some tools behind Bertha’s driver’s seat, made sure that my cell phone was charged, and headed for the highway.

I-90 is less than a mile from my house, and I use it frequently for test drives, but on the first few miles of the eastbound section into Boston, there’s no breakdown lane, and the exit after that for Cambridge and Somerville is typically clogged with traffic, and has a difficult turn-around to head back west. In contrast, I-95, though slightly further away, has an ample breakdown lane and regularly-spaced cloverleaf exits that allow easy turn-around—or bail-out onto local roads. I headed for I-95 and got on the northbound ramp, and with the car in second gear, I punched it.

Holy crap.

When I bought Bertha back, I thought that if the hot engine I’d built for it in the 1980s with the 10:1 Euro pistons, the 121 head, the 300-degree Iskendarian cam, and the dual Weber 40DCOEs was still intact; and if, when I drove it, it still had the snappy throttle response it used to—when I had the Webers jetted at Beaconwood, they said it was one of the fastest 2002s they’d ever had in the shop—I’d be happy. With one second-gear plunge of my right foot, I knew: I was happy. The thing just screamed. It is immortalized here (https://youtu.be/x1ea0wzvoq4). And this was with unbalanced Webers and only a cursory attempt at setting ignition timing. It will only get better.

On the negative side, there were some substantial metallic clunks over bumps, and I found that the five-speed, in addition to whining, gives a nasty crunch going into fourth unless you baby it. But on the plus side, by the time I got back from the drive, the visible oil burning appeared to be nearly gone.

There are still a thousand things I need to do to make the car reliable, comfortable, and safe, much less road-trip-ready. In the short term, I need to get it inspected, and in order to pass, the badly cracked windshield needs to be replaced.

But make no mistake about it: Bertha is back—ugly, loud, and proud.—Rob Siegel

Rob’s new book, Just Needs a Recharge: The Hack MechanicTM Guide to Vintage Air Conditioning, is available here on Amazon. His previous book Ran When Parked is available here. Or you can order personally inscribed copies of all of his books through Rob’s website: www.robsiegel.com.