Having repurchased Bertha, the 1975 2002 I brought up from Austin in 1984, drove away from my wedding in on Labor Day of that same year, modified out the ying-yang, then sold to my friend Alex in the early 1990s because our just-purchased house in Newton had only a one-car garage and the 3.0CSi had dibs on it, I needed to get her home.

This was a problem.

Ever since she was stolen from Alex in 1992 and recovered with suspected engine damage, Bertha had been sitting in Alex’s neighbor’s garage, a basement-level drive-in around the back of the house that was accessible because the property sloped steeply back toward a pond. The neighbor was an absentee landlord for whom Alex, a building contractor, did favors. The garage used to be accessed via a shared driveway that ran between Neighbor #1 and Neighbor #2. However, in the intervening years, Neighbor #2 had put up a chain-link fence, cutting off the driveway from Neighbor #1. A lawn eventually obliterated any evidence of garage access. Thus, it seemed that in order to get Bertha out of Neighbor #1’s garage, we needed permission from Neighbor #2 to roll back a section of the fence. If that was done, we could get a couple of people to roll Bertha onto the lawn in the back yard, point her nose in the direction of the gap in the fence, borrow a truck and back it down Neighbor #2’s driveway, use a winch to pull the car through the gap, re-position the truck, winch Bertha up the driveway, and finally tow her home.

Unfortunately we were stymied from the get-go.

Alex’s e-mails and phone calls to Neighbor #2 regarding the fence went unanswered. And when we tried to push Bertha out of the garage as a test, we found that her rear wheels were completely seized . So the entire extraction plan suddenly seemed in jeopardy.

It was at this point that Alex mused out loud, “If she ran, we could probably just drive her right up the other side of the house. There’s no driveway there, but I think there’s enough room.” As with the plot of the movie Inception, this simple idea, once seeded, gradually came to consume me.

The other side of the house: Surely there’s enough room to drive Bertha up—if she could be made to run.

“I thought you said you rolled her into the garage 26 years ago because the engine was damaged after she was stolen and recovered,” I said.

“No,” said Alex. “I drove her into the garage. Hell, I drove her home after the police found her. She ran; she just sounded like a chainsaw.”

“So,” I joked, “Bertha—can I say it?—ran when parked!” With Alex, who knows that I published a book called Ran When Parked last year, and me standing right next to Bertha—which clearly was in deader-than-Millard-Fillmore-basket-case condition—we shared a good laugh.

One of the things I say in Ran When Parked is that the longer a car sits, the less important the whole “ran when parked” thing becomes, and the consequences of its sitting—seized engine, stuck brakes, bad hydraulics, rust-contaminated fuel system, on and on—become the dominant factor.

I didn’t buy Bertha to “do a Louie”—to resurrect her where she sat and then drive her home. Any mechanical work is far easier in your own garage with access to all of your tools, your coffee and sandwich-making materials, your bathroom, etc. But in order to extract Bertha from her 26-year tomb, I had to get her capable of rolling. So it seemed that I needed to dip at least a toe in the waters of resurrection.

Thus began a week of daily trips back and forth to Alex’s neighbor’s garage. I loaded the E39 with a small floor jack, jack stands, tools, a MAPP-gas torch, and a fire extinguisher, and began dealing with the seized rear wheels.

When we say “seized wheels,” we almost always mean “seized brakes.” Disc brakes are easier to un-seize than drums because the components in disc brakes are exposed; you can usually tap the pads laterally to unseize them from the rotors. Worse comes to worst, you can pry the calipers completely off.

Seized drum brakes, however, are more difficult, since the drum itself covers up the shoes that are sticking to the inside of the drum. The tried-and-true method for un-seizing drums is smacking the flat surface with a small sledgehammer to break the bond of corrosion between the shoes and the drum. Other methods, like backing off the adjusters and using heat on the lip between the drum and the hub, are usually only effective if the drum already rotates and what you’re trying to do is get it off.

Fortunately, with a good smacking, both drums gave it up, and the rear wheels rotated freely. Alex brought over a small air compressor and we inflated the long-flat tires. I was surprised that they actually held air, but they did.

Bertha was now officially a roller.

I conducted a leak-down test on Bertha’s engine.

But with no word yet from Neighbor #2 about the fence, the Inception thing—the idea that Bertha wasn’t rolled into the garage, that the condition of her engine might not be a showstopper to resurrection, that maybe I could get her running and just drive it her up the left side of the house—began to take hold. How fubarred was the engine? Could it be easily made to run? I’d already verified that the engine rotated freely. Since there was now a compressor in the garage, I ran home and got my leak-down tester. A compression test will tell you if there’s low compression in a cylinder, but a leak-down test will tell you why. Basically, you rotate a cylinder to top dead center, then pump it full of air. The leak-down test will tell you the ratio of air being passed to air being held, but what’s really important is where air being passed is going. Any old engine will have some amount of air leak past the piston rings and into the crankcase, but if an exhaust valve isn’t sealing, you’ll hear air hiss out the tailpipe, and a bad intake valve will send air out the throttle body.

I first adjusted the valves to make sure that no valves were stuck open because they were too tight, then did the leak-down test. When I did Cylinder #1, air hissed menacingly out the forward barrel of its Weber. Conclusion: Cylinder #1 had a leaky intake valve. This was consistent with an intake valve being bent from someone over-revving the engine, which is exactly what Alex said he thought happened 26 years ago.

But the other three cylinders looked good—and three cylinders should be enough to start a 2002 engine. We were go for attempted resurrection.

In Ran When Parked, I go into a lot of detail on how to correctly start and sort out a long-dead car. In contrast, when you see videos where people just jump-start and begin cranking a decrepit car, that process can be harmful to the engine. At a minimum, you want pre-lubricated cylinder walls, clean oil, clean gas, and no rodent detritus getting sucked from the air cleaner into the engine. I pulled Bertha’s plugs, squirted Marvel Mystery Oil into the cylinders, and turned the engine over by hand five or six times. I dumped fresh oil over the valve train and changed the oil and filter. The next day, with fresh oil in the pan, lubricated cylinder walls, and adjusted valves, I dropped in a battery, verified that the starter worked, and did a compression test. It correlated with the leak-down test: #1 had very low compression, and the other cylinders were much higher, though uneven. And while the starter was spinning the engine, I heard nothing that made me think, “Stop this madness right now before you break something.”

So, the toe felt good. Wade in up to the knees?

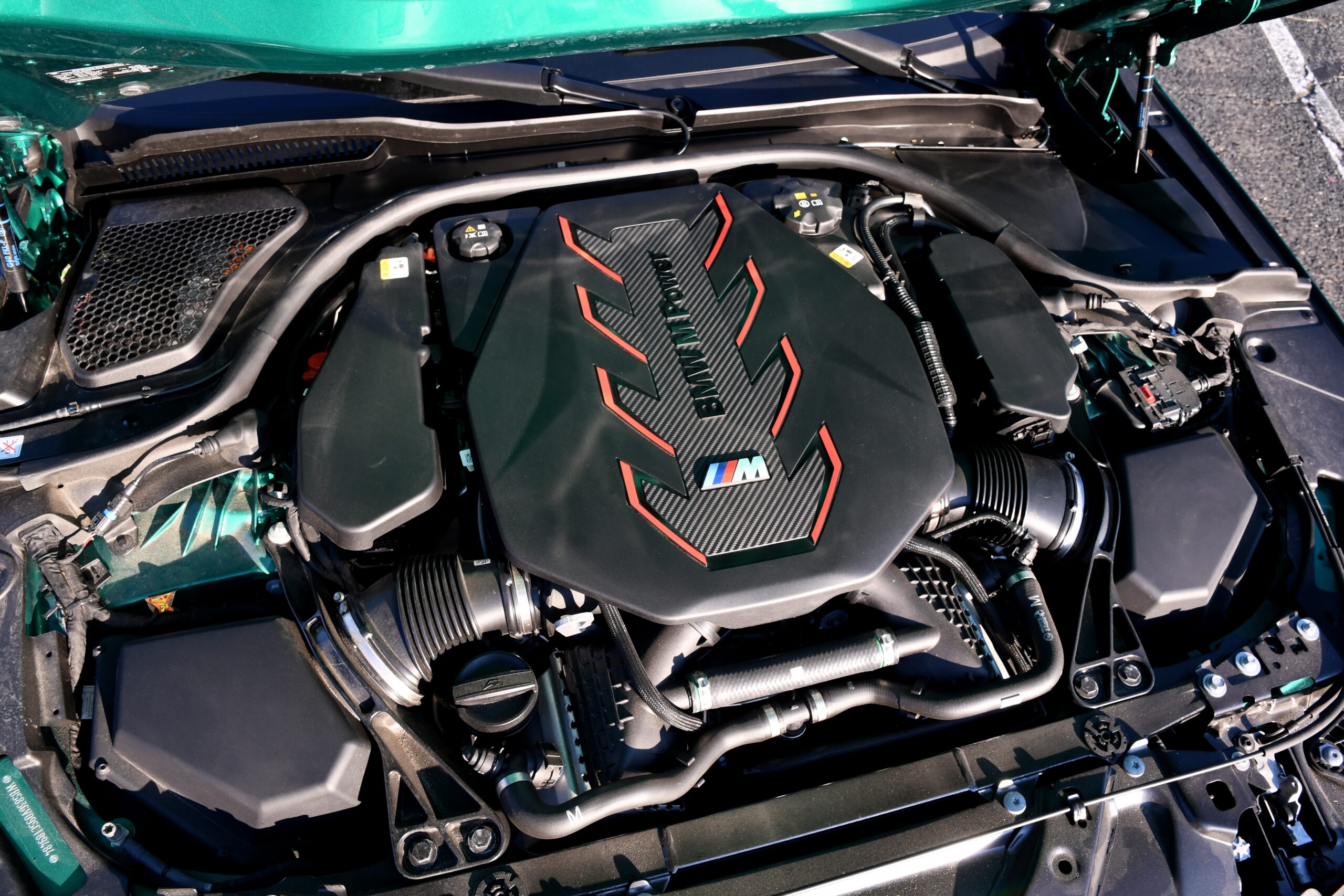

I love the process of resurrecting long-dead engines. The mantra on any car is spark and fuel, and on a car like a carbureted 2002, that’s pretty easy. Bertha’s coil and distributor had been raided years ago, so I installed known-good ones. I verified the presence of twelve volts at the coil’s “+” or “15” terminal when the key was cracked to ignition. I then hooked up a remote starter switch to the starter solenoid to make under-hood testing easier.

While wearing a rubber glove, I held the end of the fat wire coming out of the center of the coil about ¼” from ground and hit the switch. This verifies the presence of spark going into the center of the distributor cap. The plug wires were in terrible shape, their screw-in connectors having pulled out of the wires. Initially I replaced them with a NOS set of VW wires that I’ve had kicking around for 30 years, but they didn’t fit correctly over the plug ends, so I repaired the plug wires and connectors that had been on the car. I took a spare spark plug, connected a plug wire to it, held the plug’s electrode against ground, and cranked the engine. Spark? Check.

Next, fuel.

You really, really don’t want to just dump gas in the tank of a long-dead car and see what happens, as odds are that the gas tank is rusty and the rubber fuel lines are junk. I use an incremental approach of disconnecting the fuel line, using starting fluid, and seeing if the car wants to start. I’d already pulled off the air cleaners and checked for debris. I tried opening the throttles, but found that the linkage was seized at the pedal bucket (very common on long-dormant 2002s). I disconnected the linkage rod, lubricated the throttle-body shafts, and verified that they turned freely. I gave a good blast of starting fluid into all four open barrels of the Weber 40DCOEs and pulled the trigger of the remote starter switch.

On a well-maintained car, if you do this, the engine will blast into existence, run for a few seconds, and then die. Bertha didn’t do this, but she did burble hopefully and show signs that she wanted to start. It was enough for me to take the next step.

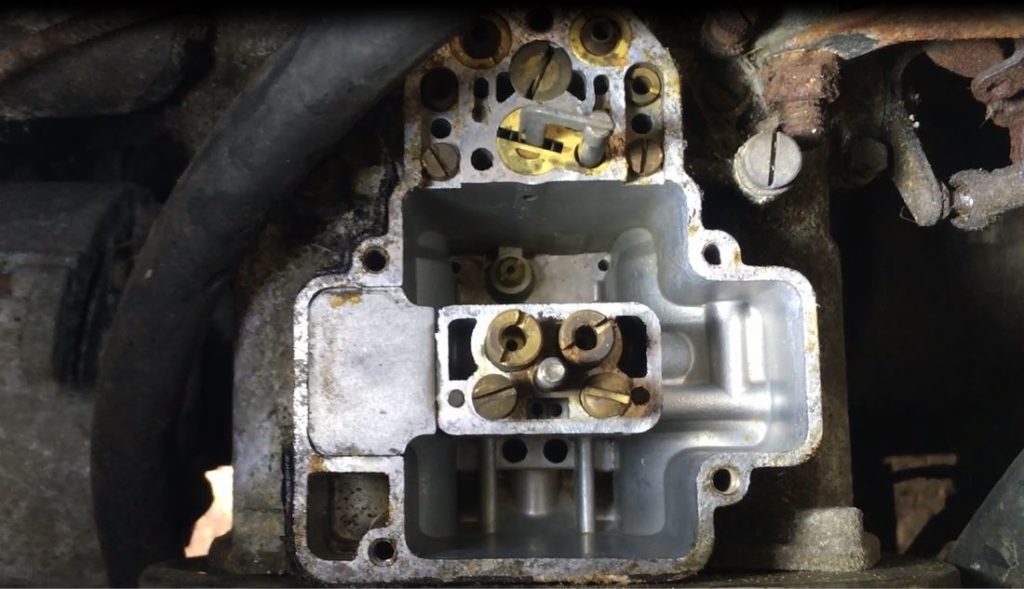

I pulled the tops off both Webers to check the float bowls. When you do this on a car that’s been sitting for decades, you may find a gummy, sediment-laden horror, in which case the carbs almost certainly need rebuilding. Fortunately, Bertha’s bowls looked fine; one had a little bit of dry sediment in it which I blew out with an air nozzle from the compressor.

The float bowls of the Weber 40DCOEs looked nice and clean.

I filled up the bowls with fresh high-test gas from a can I’d brought, screwed the tops back on, and squeezed the remote starter switch. With some feathering of the throttle, I soon had the engine idling.

Bertha had, incredibly, awakened.

Over the next few days, I completed the rejuvenation of the fuel system. The gas tank was surprisingly clean, but I pulled it out, took it home, threw a chain in it, shook it around to dislodge any loose scale, washed it with water, and let it drain overnight. I re-installed it, changed every rubber fuel line, and replaced the small electric fuel pump that had been removed from the trunk. I dumped five gallons of high-test in the tank, primed the float bowls, and the car jumped to attention when I cracked the key. It revved horribly, which turned out to be due to a missing synchronization screw that was allowing one carb to open long before the other. I replaced the screw, and the engine began revving surprisingly easily, considering the non-sealing #1 intake valve. (See the video here.)

I was now in in resurrection’s waters up to my waist.

As I say in Ran When Parked, although it’s incredibly exciting to revive a long-dead car, that part is often far easier than the subsequent steps required to get it moving, much less driving, much less driving safely and reliably. I already knew that the accelerator was seized in the pedal bucket, but I picked the broken glass from the shattered passenger window off the driver’s seat, got in the car, and tried the other pedals and controls necessary for motion. The clutch hydraulics, miraculously, appeared to function; when I depressed the clutch pedal, it was neither seized nor floppy, and felt like it was separating the pressure plate from the flywheel (any of these things can malfunction in a long-dead car).

In contrast, the brake pedal was so hard that I couldn’t tell if it did anything. And the gearshift was completely seized up, fortunately in neutral. I could easily move it laterally, but not forward or back, indicating that the seize point was likely in the linkage, not in the transmission.

The often-troublesome accelerator linkage rod goes through the pedal bucket.

I spent the next two days dealing with the accelerator and gearshift. Both required working under the car (which was disgusting) and inside the car (which was more disgusting). The accelerator repair necessitated removing the bendy linkage rod, scraping the rust off it, lubricating, and reassembling. For the gearshift, copious quantities of Silikroil penetrating oil combined with massive amounts of leverage from a pipe over the gearshift lever freed the linkage just enough to get the car in and out of gear.

While I was under the car, I checked the driveshaft. The giubo was cracked but intact, and the center support bearing looked okay; neither appeared to be an impediment to moving the car a short distance.

With the accelerator and gearshift linkages fixed, I started the car and successfully moved it five feet forward and back in the garage: Bertha was officially mobile, and I was in up to my chest.

Normally, you’d then try to move a car about twenty feet, shifting gears and testing the brakes, but in front of me was the nice grassy backyard; I didn’t want to make any tire tracks without a good reason. Alex still hadn’t heard boo from Neighbor #2 about taking down a section of the chain-link fence on the right side of the house, so at about noon on a Sunday—one week from when I’d started the in-situ resurrection I’d never planned on—I went back over and sussed out Alex’s comment that there was probably enough room to drive the car up the left side.

There did appear to be ample room, although it meant driving over a little bit of non-grass ground cover. Unfortunately, a small Honda was blocking the place where I needed to drive over the sidewalk and onto the street.

I thought I could drive Bertha up this hill. Wouldn’t you?

While we waited for the ill-placed Honda to move, I decided to try driving Bertha up to the sidewalk. I first verified that the brakes functioned by making sure that if I stood on the brake pedal and let out the clutch, it stalled the car (wouldn’t want it to roll backward into the pond, right?). Then, in her maiden voyage, I drove her out of the garage and onto the lawn in the backyard, and turned her into position to drive up the hill. But when I tried to ascend to the sidewalk, a combination of stumbling at higher rpm—likely due to the bad valve—inconsistent clutch slippage—likely caused by rust on the flywheel and pressure plate—and my impression that the tires were slipping and ripping up the yard (they weren’t) caused me to abandon the attempt about ¾ of the way up.

I let her roll back down. (This first attempt can be seen here.)

I thought, not good! Not good! The car was now sitting on the lawn in someone’s back yard. I was up to my chin, at the point of no return, and I didn’t like it.

In the middle of this existential crisis, a tenant came out of the house and watched intently. He was very interested in the fact that this car had been sitting in the garage under the house the entire time he’d lived there, and he didn’t know about it. I explained what we were doing, and said that we’d get the car out as soon as we could. He didn’t seem concerned about the fact that the car was sitting in the yard, or that it had made tire tracks across the lawn and up the side of the house. But he did say that the work I’d been doing over the week had smelled up the house with gas and exhaust fumes.

All of a sudden I realized how far out on a ledge I’d crawled.

Going over there with tools to unseize the brakes seemed the most natural thing in the world to me. Doing a little more each session, checking for spark, hauling over a can of gas, starting, idling, and running the engine—it never occurred to me for a moment that I’d crossed a line, because not only wasn’t this my garage, not only was it attached to a house, it was under a house that people lived in. It was a wonder that I’d gotten away with it. Perhaps I only did because, much of the time, I was doing this during working hours when folks likely weren’t there.

A few minutes later, the inconveniently-placed Honda vanished, clearing a path onto the street. I grabbed the pair of low ramps I’d brought, positioned them at the curb, and made the second attempt. Between the car’s non-existent exhaust and the mechanical noise from the engine, Bertha did sound, as Alex said, like a chainsaw. But with a lot of throttle and enough clutch slippage to take a year’s life off the clutch disc, up the hill, over the sidewalk and curb, down the ramps, and onto the street Bertha drove, 26 years after she’d been put away. It was amazing. (The video can be seen here.)

The flatbed: a hundred bucks well spent.

Although friends on Facebook were egging me on to drive the car the five miles home, that was out of the question. In the first place, as I say in Ran When Parked, the sort-out process involves driving a car five feet, then twenty, then a hundred, then around the block, then a mile, each time checking for leaks and likely returning to the garage to fix something. The barely-functioning brakes alone ruled out a drive on public roads.

I appreciated the Facebook comment from my friend Lindsey Browne: “I’ve seen people cause thousands of dollars worth of damage because they don’t want to spend a hundred bucks for a tow.” Thanks, Lindsey. Second, the car was not only flagrantly illegal, it looked like it was flagrantly illegal. I debated whether to try to use my AAA or Hagerty benefits (technically, neither will tow an unregistered car) or borrow a truck and rent a U-Haul transporter, but in the end I simply called a local towing service. They were there in twenty minutes, and for a hundred bucks the car was flat-bedded to my house. After the drama of the resurrection and the extraction, the actual delivery was anticlimactic.

So: Bertha is now home. Ironically, or perhaps poetically, she has come back to the house into which she was denied entry 26 years ago due to lack of garage space. Indeed, she is now occupying the place of honor on my mid-rise lift.

All my other cars must be saying “What the—?!”

Many folks have asked me what my plans are for Bertha. For a guy whose recent Roundel column included a series of Hack Mechanic Tips For Sane Living, one of which said, “Be mercilessly rational,” I’ll freely admit that this isn’t a purchase that made a lot of sense, and that there is no universe in which “restoring” the car makes any sense whatsoever. I usually refer to car purchases as crimes of opportunity, but this was one that I actively pursued, so I must’ve really wanted to do it, perhaps at some deep-seated masochistic level.

I do love my historical connection with the car, the challenge, and the story. And I love helping cars be whatever it is that they seem to want to be. If I can get the rodent smell out of her, get her running, get the performance and throttle response of the Webers, the 300-degree Iskendarian cam, and the 10:1 pistons back to what they were 30 years ago, and have her be the Mad Max-style troublemaker of the fleet, maybe that’ll be enough.

But if one more person says, “Have it ready for Oktoberfest in Pittsburgh in July! You can do it! Go. GO. GO!” I swear, back into Alex’s neighbor’s garage she goes.—Rob Siegel

Rob’s new recent book, Just Needs a Recharge: The Hack MechanicTM Guide to Vintage Air Conditioning, is available here on Amazon. Or you can order personally inscribed copies through Rob’s website: www.robsiegel.com.