Is there a better stress test of a vehicle’s operational condition than a long road trip? While relatively short around-town trips may not reveal issues, a vehicle will let you know what it needs after you’ve been in the driver’s seat for hundreds of continuous miles. What’s that sound? What’s that smell? Is that coming from the car in front of me or is that my car?

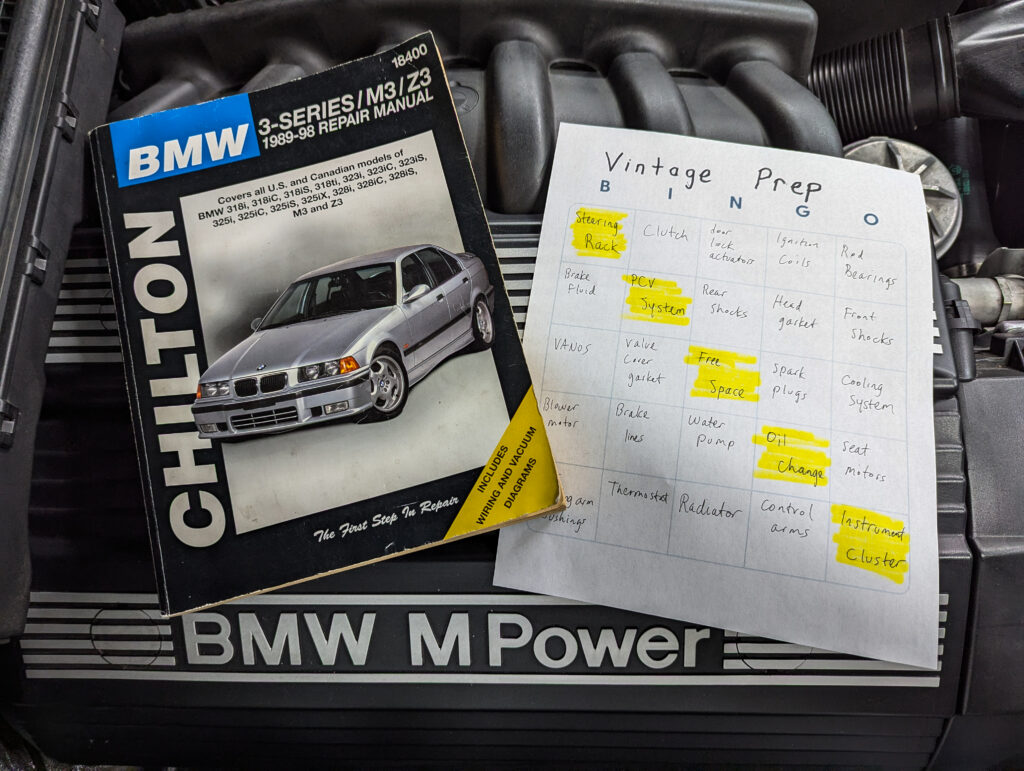

For the past five years, I’ve been making the 500-mile trek from Northern Virginia to Asheville, North Carolina for one of the largest and best classic BMW gatherings in the world: The Vintage. And every year, during the months leading up to this classic car pilgrimage, I play a little game that I like to call Vintage Prep Bingo. Imagine a Bingo card with rows and columns of potential automotive problems. Of all the possible mechanical failures that could happen, what do I think should be addressed for a successful road trip?

Given that 2025 was the first—and possibly only—year the third-generation 3 Series (E36) chassis would be allowed to register and be parked alongside other classic BMWs on the Vintage showfield, my eleven-year-old-daughter Avery and I opted to take our high-mileage 1998 BMW M3 sedan. While this E36 was running relatively well, I decided to address a number of items on my Vintage Prep Bingo card to ensure a smooth 1,200-mile round trip.

This included things like a full M Sport Parts instrument cluster refurbishment to resolve the random and increasingly frequent cluster resets while driving. The leaky steering rack and power steering hoses were replaced. New tires—and wheels!—replaced the plugged and aging set. A Positive Crankcase Ventilation (PCV) system replacement resolved a recent increase in oil consumption. And an oil and filter change completed my Vintage to-do list. Beyond addressing those concerns, I had spent the previous two-and-a-half years going through the rest of the car, addressing everything from seat motors and door lock actuators to a head gasket and cooling system replacement. What could go wrong?

Well, I’m pleased to report the ten-hour journey from Northern Virginia to Asheville went off without a hitch, aside from a couple of minor issues encountered by other cars in our caravan crew. The myriad of tools I packed—a floor jack, jack stands, sockets, extensions, wrenches, an electric impact, screwdrivers…we could be here all day—actually came in handy at a rest stop when an E24’s power steering pump bolt backed itself out. I joked, “As long as I don’t have to use these tools on my own car during this trip, I’ll be happy.”

I shouldn’t have said that. That was a dumb thing to say.

The next day when we were en route to The Ultimate Driving Museum for The Vintage Open House, I started to smell oil as we waited for a traffic light to turn green. More precisely, it was burning oil. My first thought was, “That can’t be my car. Is that my car?”

Just to be sure, when we parked I popped the hood to investigate. That’s when I was greeted with a cloud of smoke. Peeking under the car, I could see oil dripping from the bottom of the bell housing of the transmission. Oil had also dripped onto the hot exhaust while driving, which caused the smell and smoke.

The floor jack and jack stands made their second appearance from our E36’s trunk in as many days, this time in the parking lot of Plant Spartanburg, which despite the stressful situation, gave me a chuckle. Fitting, right? Jim Gerock, a BMW CCA member of our caravan, lent a hand and additional tools in diagnosing the issue. It wasn’t a leak from the valve cover gasket, or the back of the head, or the oil pan gasket, or anything else in the vicinity. Our best guess: the rear main seal. I didn’t see that coming and “rear main seal” was not on my Vintage Prep Bingo card.

For those not familiar, an engine’s rear main seal is typically a circular rubber seal that surrounds the end of the crankshaft (where it connects to the flywheel and interfaces with the transmission) and is supposed to keep oil in. While the seal itself is inexpensive, replacing it on an E36 involves removing the exhaust, driveshaft, transmission, and many other ancillary items like the shifter, clutch hydraulic lines, and so on.

Suffice to say, while the spirit of Vintage weekend has fueled many extraordinary mechanical repairs by Vintage attendees in hotel parking lots, this wouldn’t be one of them. Fortunately, it wasn’t leaking enough to stop our father-daughter road trip. With frequent oil-level checking and topping up as necessary, Avery and I were able to enjoy the remainder of Vintage weekend and make it back home safely.

Looking through the M3’s maintenance history, the rear main seal had been replaced about 35,000 miles ago, as part of a clutch and flywheel (and a number of other while-you’re-in-there items) replacement . It should’ve lasted much longer than that, so what would cause the rear main seal to fail so quickly?

Initially, my best guess was that I caught the PCV system failure too late, which can cause increased pressure in the crankcase and result in engine seals being pressed outward and starting to leak. The only symptoms of a PCV system issue that I recognized in this M3 were increased oil consumption—which I mostly chalked up to a 256,000-mile S52 engine—and some erratic oil dipstick readings over the course of a few weeks. There weren’t any odd sounds or leaks, and the E36 had been running well otherwise. While I had replaced the PCV system on our E36 four weeks before The Vintage road trip, which did resolve the oil consumption and erratic dipstick readings, the damage had likely already been done, with the result becoming quite evident after a long day of driving. (If you’re interested in watching a video about replacing the S52’s PCV system, click “Play” below!)

A week after returning from our big road trip, it was time to take our E36 to the professionals at RRT Automotive for a proper diagnosis and repair. As much as I wanted to receive a call and hear, “It just turned out to be the valve cover gasket, and oil was leaking down the back of the head and collecting at the bottom of the transmission’s bell housing” this was not meant to be. It was in fact the rear main seal. Fortunately, the oil leak had not contaminated the clutch and parts costs were kept low. The bulk of the cost of the repair was in labor, due to the aforementioned items that needed to be removed to access and replace the $40 seal.

I spoke with RRT Owner and Lead Technician James Muskopf about the potential cause of the seal failure. It turns out the seal wasn’t pushed out due to crankcase pressure like I had hypothesized. If anything, it was actually pushed in a smidge. So, it’s still somewhat of a mystery at this point, but the PCV system issues still may have contributed to the rear main seal failure. You can be sure that I’ll be keeping a close eye on things.

It feels good to have our E36 back on the road, leak free, and ready for our next road trip. In fact, similar to my father-daughter trip to the Vintage with Avery, my eight-year-old-son Carter and I may take it on our own father-son road trip 250 miles northwest to the Pittsburgh Vintage Grand Prix this summer. I should probably revise my Vintage Prep Bingo card beforehand. —Mike Bevels

Tags: family fun restoration Vintage