Last week I presented a short (?) photographic history of the 1973 E9 3.0CSi I bought in 1986—a car I still own. Included were two pics taken around 1989 of the engine being replaced curbside in front of the garage of what was then my mother’s house in Brighton (Boston), a stone’s throw from the MBTA B Line that goes to Boston College (and coincidentally continues to Newton, where I’ve lived for over 30 years).

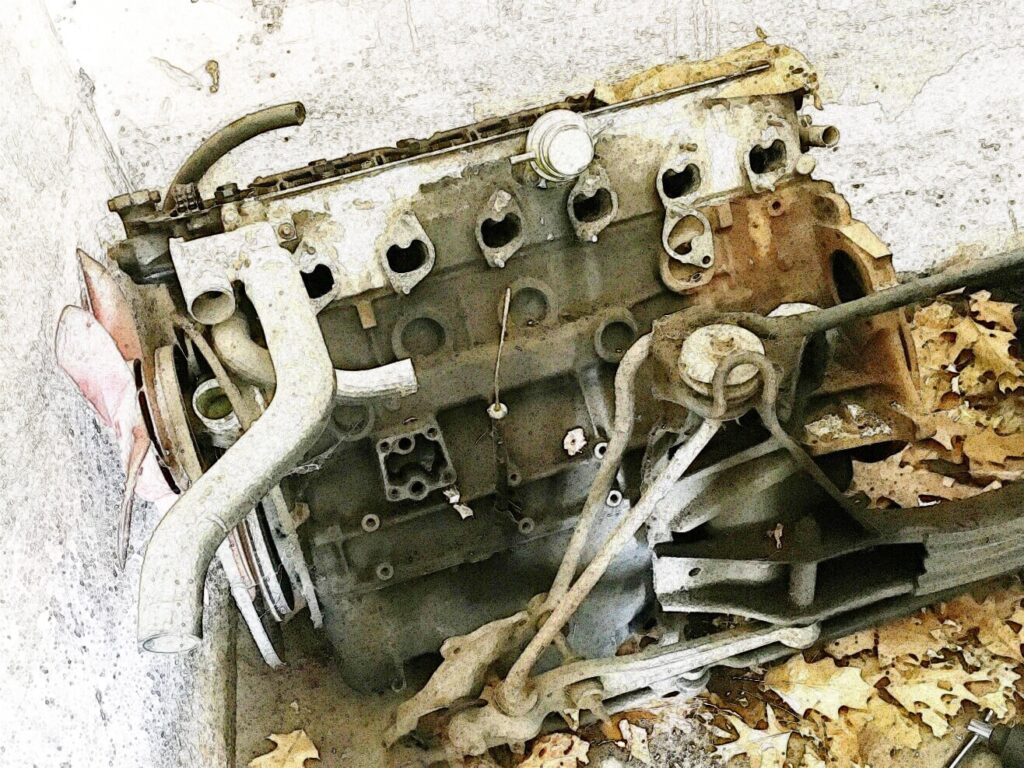

It will probably surprise no one to learn that the original engine is still sitting where I dragged it, in the back of that garage—along with a front subframe from a 2800 CS that I had parted out a few years earlier.

Of course it’s still there. Why wouldn’t it be? Moving it requires work, and I’ve had no reason to do it—until now.

When my mother passed away in the summer of 2019, my sister and I inherited the house. She still lives there. We’re finally getting around to some long-delayed improvements to the property, which begin with cleaning out the 40-year accumulation of stuff, some of which is still mine, even though my wife, Maire Anne, and I moved out in 1992. About five years ago I got rid of the mother lode of parts that were sitting in the basement and under the front porch, but the engine in the garage, not being as easy to move as the hoard of doors and transmissions, remains.

It sits there, glowering at me.

The problem of an old engine hanging around like a party guest who doesn’t know when to leave is not an uncommon one for those with our unfortunate genetic predisposition to cardom. Even if you haven’t been drilled into thinking that numbers-matching engines are automatically a big deal in terms of a car’s resale value, maybe you’re like me and pulled an engine 33 years ago because it was tired and because you found a great deal on a newer engine, and the old one is just kind of still there.

In my case, the path to the engine that caused the original to be jettisoned was pretty unusual.

The M30B32 that’s currently in the E9 was from a very-low-mile 1984 533i that missed a curve on Storrow Drive and wound up in the Charles River. My friend Alex bought the car, although I’m not really sure what he planned to do with it. He had it towed to the grounds of a house he’d bought in Newton to refurbish and flip (the house, not the car. Well, I don’t know—maybe the plan was to refurbish and flip the house and the car). But when the house was done, the car was still on the property, so it was hauled off.

A few years later, entirely by chance, I drove my recently painted E9 home from some trip, and stopped at a bottom-dollar used-car wholesaler in Lynn to see what they had on the lot. The owner saw my car and said, “Hey, any chance you need an engine for that? I have a really low-mileage one I’d sell for three hundred bucks. Only thing is that it’s from a car that took a swim in the Charles River.”

I burst out laughing. “You didn’t buy the car from a guy named Alex, did you?” I bought the engine, tore it down, cleaned and resealed it, reassembled it, and converted it from the Motronic configuration to one that could use the original old-school distributor, this last part a decision I eventually came to regret although it made sense at the time.

These days, if you plan to keep the original numbers-matching engine, you pickle it, meaning you pour something like Marvel Mystery Oil down the cylinder bores, then seal up every opening so dirt and rust can’t get in, and keep it clean. In a perfect world, you even crate it to convince yourself that you’re treating it with the appropriate reverence.

I didn’t do any of that. Why would I? It wasn’t some one-of-100 racing engine, it was just a tired old motor. If it wasn’t, I wouldn’t have replaced it.

The fact that in the photo above, the valve cover isn’t even on is a bit of extra abuse that I’m not proud of. It was part of the de-Motronicizing I performed on the engine, which included grinding the tabs off the front of the distributor that drove the original front-facing Motronic rotor, replacing them with a thread-on slotted nut that ran the old-style distributor drive gear, and replacing the Motronic “distributor” cap with an old-style front upper timing cover that hosted the conventional distributor.

Once I got the replacement engine in the car and buttoned things up, I found that the front-most hole in its valve cover didn’t line up with the hole in the backdated upper timing cover. I didn’t think that this was a big deal, but when it began leaking oil from that spot, I pulled the valve cover off and swapped it for the one from the original engine. I would’ve bet money that I’d put the Motronic valve cover on the original engine in the garage in order to keep dirt out of the valve train. Why it’s not there is a mystery.

But it’s hard for me to shed too many tears for the neglected original engine, as the economics of numbers-matching engines in E9 coupes doesn’t appear to be like that of split-window ’63 Corvettes. Variants of the E9’s M30 engine were installed in BMWs from 1968 through 1995. For many years, the go-to solution for either a tired engine or wanting more power and improved drivability in an E9 or E3 has been to find a 20-horsepower Motronic M30B35 engine and five-speed from an E34 535i and drop the whole shebang—engine, transmission, wiring harness, ECU, sensors—in. From sales on Bring a Trailer, it certainly doesn’t look like doing so is a knock on an E9’s value, as long as the swap is well done and the car presents itself as a well-executed whole.

In my case, although I say that I regret stripping the Motronics off, I did install a five-speed along with the replacement engine, and I later retrofitted L-Jetronic injection and electronic ignition out of a late E12 528i, so instead of my car having injection and ignition that’s two generations newer than it originally did, these things are one generation newer—still better than the original, still more reliable, still easier to get parts for, and looking more period-correct than the Motronic swap unless you go to the extra effort of changing the intake manifold. So it’s not as if the swap is something I regret for value reasons.

The E9’s somewhat-Frankenstein’d M30B32 engine with L-Jetronic injection from an E12 528i: Other than the air-flow meter, it doesn’t look that different from the original D-Jetronic injection. Yeah, I know: That air cleaner has to go.

As I wrote last week, if—hypothetically—my E9 ever came up for sale (and it won’t, as long as there’s still brake fluid running through my veins), there are several demerits against its value. These include the color change using a non-BMW color, the imperfect bodywork when the new fenders and nose were welded on, the use of body filler, the interior swap with a ’75 3.0CS (so the pleats on the seats and door cards aren’t correct), and, candidly, the fact that it’s been my car and “The Hack Mechanic” sure ain’t “The Anal-Retentive Do-It-Once Do-It-Right Mechanic.”

Where in this list does the non-numbers-matching engine reside? Does it have any effect on the car’s hypothetical value?

I often fall back on the “all factors being equal” straw man. Imagine two cars, identical in every respect except one. Does the color change matter? Sure. But the numbers-matching engine when the one installed is an improvement and the car isn’t dead-nuts original? It’s difficult for me to see it as an issue. So is there any reason why, after going to the trouble to drag its 33-year-dead ass from its dead storage in the garage in Brighton, I shouldn’t just drop the thing off in front of the scrap-metal dumpster at the Newton recycling depot?

No.

And yet… would you?

I began to think. And with thought came two questions. First, I asked myself, “Do you know that it’s the original numbers-matching engine?” It occurred to me that I didn’t; I was just assuming it. It was a reasonable assumption, but an assumption nevertheless.

Second, is the engine seized? It probably is; I mean, it’s been sitting for 33 years, not just unpickled, but with the valve train completely exposed. So I resolved that the next time I went over to the house in Brighton, I’d check these things out.

Obviously I could’ve gotten the car’s VIN from any number of places, including just walking down to the garage and opening the E9’s hood, but it was fun to dig the original bill of sale out of the folder. Yup, 1973 3.0CSi, VIN 226490, sold to me in all its basket-case glory on 9/17/86, for $1,700.

I really did pay $1,700 for the basket-case car in 1986. It’s even notarized.

The next time I went over to Brighton, I brought some paper towels and brake cleaner to expose the VIN on the block, and a 36-mm socket for the crankshaft nut and a breaker bar. A quick wipe revealed that this was, in fact, the original numbers-matching engine.

It’s good. Or bad. Depending on how you look at it.

My emotional reaction was, “Damn it! Now I have to keep it.”

But there was one more hoop to jump through: The engine had to turn. It was already difficult for me to imagine a universe in which the engine would ever be put back in the car, so if it was seized, I’d really have no qualms about trailering it to the dump, maybe pulling off the head first just in case my Bavaria ever needed one.

I tipped the front of the engine slightly away from the wall to make some clearance, got the socket on the crankshaft nut, and gave the breaker bar a shove. To my stunned surprise, it turned, to quote Mike Myers’ “Coffee Time” character on Saturday Night Live, “like buttah.”

Damn.

So now I feel honor-bound to keep the damned thing, and that’s a problem. Getting it out of Brighton won’t be awful, and that has to happen anyway. Rather than disassemble my engine hoist and throwing it in the back of the truck, I can just rent a little U-Haul trailer and drag the engine onto it with my Warn PullzAll (the 120V portable winch). But I don’t really have the room for the original engine in Newton. There’s certainly no room in my garage; space there is scarce and precious. It’d be difficult to get it under the back porch, since there’s not a clear path to roll it under there.

Oh, yeah—lots of room under here.

What I’d have to do is stash it down at the very end of the driveway, behind the Winnebago Rialta, which is where a whole variety of parts go to die. And why, so it can sit for another 30 years? Okay, I’m 64, I probably won’t be around for another 30 years. So, it can sit until I can deal with disposing of it when my back is even worse? Or until my kids have to deal with it? Why not just get rid of it now?

No, that’s not the correctly-colored Boston Green Z3 front bumper cover I bought on the same trip where I snagged the Recaro office chair. It’s a different one. Don’t ask.

When I helped the woman sell her deceased husband’s original-owner ’72 2002tii last fall (the Mitzvah tii), there was the same situation with the car’s original numbers-matching (though seized) engine sitting in her garage. I let the new owner know that the engine was available, but he’d need to arrange shipping. He lives in Beverly Hills, and showed zero interest in it. So I offered it for free to members of the Nor’East 02ers.

There were no takers. The engine is still in her garage, showing that the value of such things often aren’t what you’d imagine. I feel emotionally responsible for getting rid of it for her, but I know what’ll happen: I’ll drop it off at my house first and start dismantling it for parts. I mean, hey, the head, the crank—you hate to throw that stuff away. But what, I should have two dead engines in Newton? Okay, three; there’s also a long-dormant (but unseized) tii engine under the porch.

But when I was selling the Mitzvah tii, I got a call from a Porsche guy in Vermont. The very first question he asked was about the numbers-matching engine. I kind of bit his head off, launching into this lecture about how if that was his first question, it clearly wasn’t the car for him (it had had some less-than-perfect bodywork done during its restoration in the 1990s), and we shouldn’t be wasting each other’s time. He calmly responded that, with the appreciating values of these cars, what’s not important today will likely be important in the future. And I do get that.

Sigh.

The fact is that the E9’s original numbers-matching engine only still exists because it’s cost me nothing in time, effort, money, or space to let it sit where it came to rest 33 years ago. What to do with it now isn’t a head-versus-heart issue; my heart doesn’t give a crap about the engine, but two different parts of my head are giving me two different answers.

It all comes down to this: To what extent should I feel beholden to a hypothetical decision a hypothetical future owner of the car may want to have the option of making, when in the meantime the situation makes me responsible for keeping a 350-pound block of metal around until I die?

It’s a good question. I still haven’t figured out the answer.—Rob Siegel

____________________________________

Rob’s newest book, The Best of The Hack Mechanic, is available here on Amazon, as are his seven other books. Signed copies can be ordered directly from Rob here.