“Was it that long ago that I bought my first 2002, rebuilt the transmission three times before I got it right, put on a set of Pirelli P3s, and experienced the equivalent of automotive orgasm when I shifted it into second without it crunching as the ADS 200 speakers precariously placed on the back deck were cranking The Ghost in You by the Psychedelic Furs while I booted open both barrels of the miserable Solex and blasted down 183 through Austin with the German gears humming pistons pumping Castrol windows down sunroof open narcotic spring Texas night invading the car like rich warm spicy ancient breezes rolling off the Colorado river? Never mind that the car was a piece of junk. Never mind that the tranny started crunching second gear four months later. This was my first BMW. I bought it wicked cheap and fixed it myself. It’s how it all started. The memory moves me to near tears even now. I can still smell the pollen in the air. It took so little to make me happy. Was it that long ago?”—Rob Siegel, Roundel, July 1996

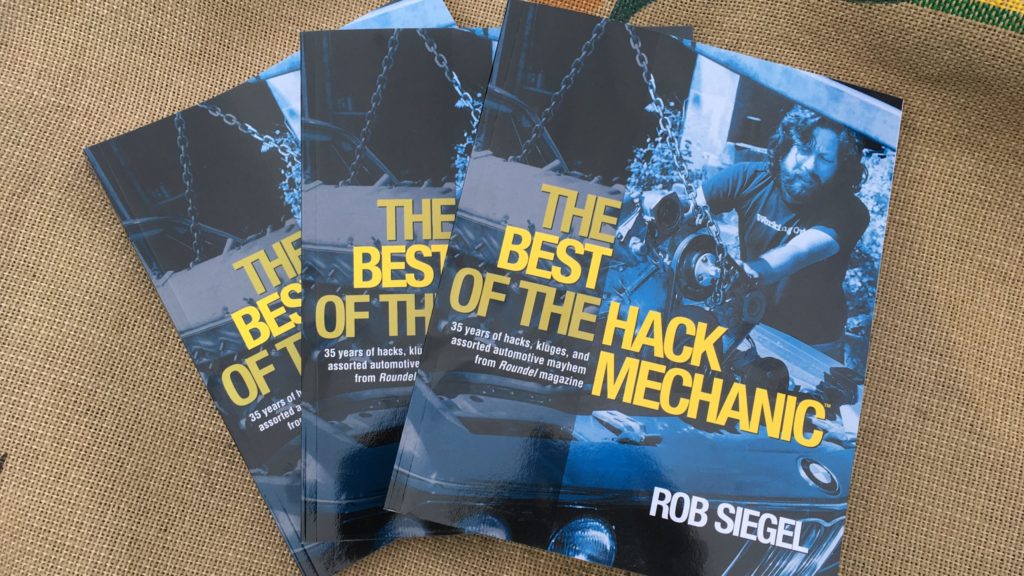

We interrupt The Endless Saga Of Zelda’s Bumper Cover with the following exciting news: My new book, The Best Of The Hack Mechanic: 35 years of hacks, kluges, and general automotive mayhem from Roundel magazine, has been released and is now available on Amazon.

First, big thanks goes out to BMW CCA executive director Frank Patek and Roundel editor-in-chief Satch Carlson for giving me permission to publish my Roundel columns.

Second, let me answer the “why now” question that more than a few people have asked me.

When I could see the 35th anniversary of my first Roundel article approaching, I thought that while 40 is a better round number, I’m 62 years old, and while I might think that I have another 40 years of columns in me, it would be actuarially unlikely. But I can pretend with a straight face that another 35 years is possible (although the thought of replacing a clutch at age 97 does give me pause).

To be clear, I’m fine. This in no way implies the impending end of either me or the column.

A brief history of my involvement with Roundel: Maire Anne and I moved to Austin in 1982, and shortly thereafter, I scratched an itch that I’d had for years: I bought my first 2002. I quickly began going through cars like others go through jeans at the knees. I met Terry Sayther, who was then proprietor of the Phoenix Motor Works (PMW) independent repair shop in South Austin. Terry was instrumental in my learning about the beat-up little car I’d just bought, and we soon developed a friendly little competition for who was fastest at snatching dead 2002s out of Austin’s driveways.

When Maire Anne and were planning to return to Boston in mid-1984, Terry recommended that I look up the BMW CCA, which was at that time headquartered in Cambridge. I did, I joined, and began poring over every issue of Roundel.

In 1985 I wrote my first article, The Heartbreak of Automotive Obsession, and sent it in to then-editor Parker Spooner. When it was published in the March 1986 Roundel, and contained the fun artwork by the late John Kessler, I was ecstatic.

I wrote and sent in a few other unsolicited articles. Parker ran them as well.

I had other things going in my life (my new marriage, my engineering career, my band), but to be able to play with cars and write about them and see it published in this was very cool magazine was immensely satisfying.

The first page of my first article, March 1986, was scanned from Roundel.

It’s a cliché to say that a phone call changed my life, but it did. In June 1987, I got a call from someone I didn’t know: Yale Rachlin. He explained that he’d been Roundel’s art director, but was now the editor; he said that he liked my stuff, and asked if I was interested in becoming a Roundel staff member and writing for the magazine regularly.

Obviously, I accepted.

The phrase “Hack Mechanic” first appeared in September 1990 in the title of a two-part piece I wrote called Confessions of a Hack Mechanic. In it, I laid out why I (and, as it turned out, many other people) enjoyed working on cars, and why having to scrape myself off with a spatula and wash my hair with Dawn wasn’t necessarily a bad thing. Confessions of a Hack Mechanic was used as a heading for six articles before being shortened to The Hack Mechanic, which began appearing as a monthly column in April 1992.

Since I’d been previously used to writing well-researched pieces, editing and burnishing them for weeks, and only sending them in when I was good and ready, writing short pieces under a deadline felt unnatural (actually, initially it was nothing less than terrifying), but as the story I’ve told a thousand times goes, Yale said, “You do fix cars, don’t you? Did you fix anything this month? Write about whatever it was you did”—at which point the column took on the still-recognizable form, as Satch would eventually describe it, of me getting myself into BMW-related trouble (and hopefully getting out of it as well).

When I describe that first 2002 I bought in Austin as equal parts Colorado Orange paint, Bondo, and surface rust, I’m not exaggerating. Holden the cat, however, and the removable ADS speakers, were very cool. I’ve had Facebook friends tell me they’ve gone to this exact spot in Austin at the intersection of Speedway and West 35th and swear that they can still see the oil stains.

You have to remember that this was all before the Internet, before enthusiast forums and blogs. I didn’t know that there were all these other people who, like me, tried to fix their own car so they wouldn’t have to take it to the dealer every time it burped or coughed. The fact that there were folks who read the column because, in some sense, I was like them, was the biggest surprise of my life.

The column The Hack Mechanic followed my odd path as I bought and daily-drove whatever ten-ish-year-old hundred-fifty-thousand-ish-mile BMW made sense, until it got too needy and rusty, at which point I jumped to something slightly newer, all the while still owning and maintaining my enthusiast cars, mostly 2002s and my ’73 E9 3.0CSi.

Then, when we bought our house in Newton in 1992, since it had only a one-car corrugated metal garage, and since that clearly had to keep the E9 out of the elements, any other car that I acquired had to sit outside—meant no more 2002s.

Then, when the new garage was built in 2005, history repeated itself and I began buying every affordable 2002 I could find that made sense (and many that didn’t). In many ways, surprisingly little has changed since those early heady, scrappy days in Austin.

Looking back over the columns, it’s astonishing to me how early many of the themes in which I still trade appeared: “Siegel’s Seven-Car Rule” (the justification that every car nut needs a daily driver, a family hauler, a track rat, a beach vehicle/tow monster, a drop-top roadster, a pampered classic, and whatever the current car happens to be). “The Big Seven” things likely to strand a vintage car. The idea that, by working on things you can actually fix (unlike, say, healthcare), you are ordering your world, and it’s no surprise that that gives you pleasure. The fact that doing one thing a night, no matter how small, can help move a project toward completion.

If there was ever a shift in content or tone, it was that when I began writing online in 2013 for what was then called Roundel Weekly (now BimmerLife), and those pieces became very rooted in whatever I happened to be working on, while the monthly Roundel magazine pieces may have become a bit more philosophical.

Putting together The Best Of The Hack Mechanic (TBOTHM) was wonderful dive into my last 35 years of BMW geekdom. With nearly 400 columns and articles, there were obviously too many to put out a “Complete Hack Mechanic” volume. Plus, re-reading the pieces, it was clear that not all of them were gold. [Cough-cough gasp snort.—SC]

There were columns I remembered well, as did some of my readers (I’ve had steady requests over the years for “that crazy one where you locked yourself out of a running car”—yes, it’s in the book), and I found others that I had no recollection of at all—including one where I described, in great detail, looking at an affordable E24 M6. I have no explanation for the mental lapse. Maybe I inhaled too much starting ether while trying to get the damn thing running.

I rarely get in the way of Eric King, the person who has designed my last five books, but as he began to lay out TBOTHM, I had a strong emotional preference for a format that was bit heavy and blocky, with bold lines at the top and bottom and around the callouts, a design that emulated the look of Roundel magazine in the mid-to-late ’80s, when Yale was still manually using an X-Acto knife to cut up typeset text and illustrations, and hot wax to paste them onto sheets of oaktag.

If the design of the book evokes feelings of the layout of mid-to-late ’80s Roundel, good: It’s supposed to.

Photos proved to be an interesting challenge. Initially I thought that the book wouldn’t be an illustrated volume; after all, it was mostly a collection of my columns, and the columns, unlike the articles, never included photos. Then I thought that I’d include the handful of original Yale Rachlin-shot-and-developed-and-enlarged photos that accompanied some of the early articles (the cover shot, with me pulling the engine from my E9 on the streets of Boston in front of my mother’s garage, came from the very first Confessions of a Hack Mechanic article). Then Eric and I thought we’d include a few multi-page photo galleries and space them equally throughout the book. But eventually I opened up the floodgates, scanned many of my old photos and a few from where the original articles appeared in old Roundel magazines, and populated the book with as many photos as possible that were representative of the content, even if the photos were digital and taken decades later.

A few photos, like this one from the April 1989 Roundel story “The 2002 and the Ferrari,” were scanned directly from the magazine.

Favorites? Well, you can decide for yourself, but to me:

- The stuff that keys are made of

- Looking over the edge

- The coming of the asteroid

- The lion in winter

- Saving 2590507

- Driving the royal road to the unconscious

- Hank the car guy

- My father’s tools

So there you go. I’ve published my Best Of book. It must be all downhill from here. I was 24 when I started wrenching on BMWs, and 28 and all full of piss and vinegar when I began writing about that practice. Now I’m 62, and think that my bodily liquids probably consist mostly of a mixture of Castrol 20W50 and brake fluid.

But on the bright side, many people have years pass with barely any demarcation, while I, on the other hand, have a complete printed monthly enumeration of my automotive activities—and most of my highly questionable decisions. My tenure with Roundel has outlasted everything else I’ve done with the exception of my marriage. My life’s work? If I didn’t still harbor hope of recognition as a singer-songwriter, I’d say yes. My life’s uncomplicated passion and pleasure? Hell yes.

I always hated that “fat Hack” caricature second from the left. AND WHO THE HELL FIXES A CAR WITH A MONKEY WRENCH? I’m a Hack Mechanic, not a—oh, wait a minute….

To paraphrase Star Trek: The Wrath Of Khan, I have been, and always shall be, your Hack Mechanic. I’m game for another 35 years. You? Good. It’s a date. See you in 2056 with TBOTHM Vol II.

But that clutch, I’m not so sure about.—Rob Siegel

Rob’s eight books are all available on Amazon, and signed copies can be ordered directly from Rob here. He is currently sold out of The Best of The Hack Mechanic, so right now, Amazon is the only place to buy it, but he’ll have more copies in early June.