Last week, I wrote about nearly taking my 40-year-owned 1973 3.0CSi for a weekend in Vermont with my wife until a cursory pre-flight check revealed that it was surprisingly low on brake fluid. Even though the car likely won’t see much asphalt until spring, I didn’t want to leave the mystery hanging, so with the car still in the garage, I stomped hard on the brake pedal about a dozen times. I felt no change in the pedal, didn’t see the level changing, and saw no fluid beneath the car, so I drove it and did the same thing. Still nothing.

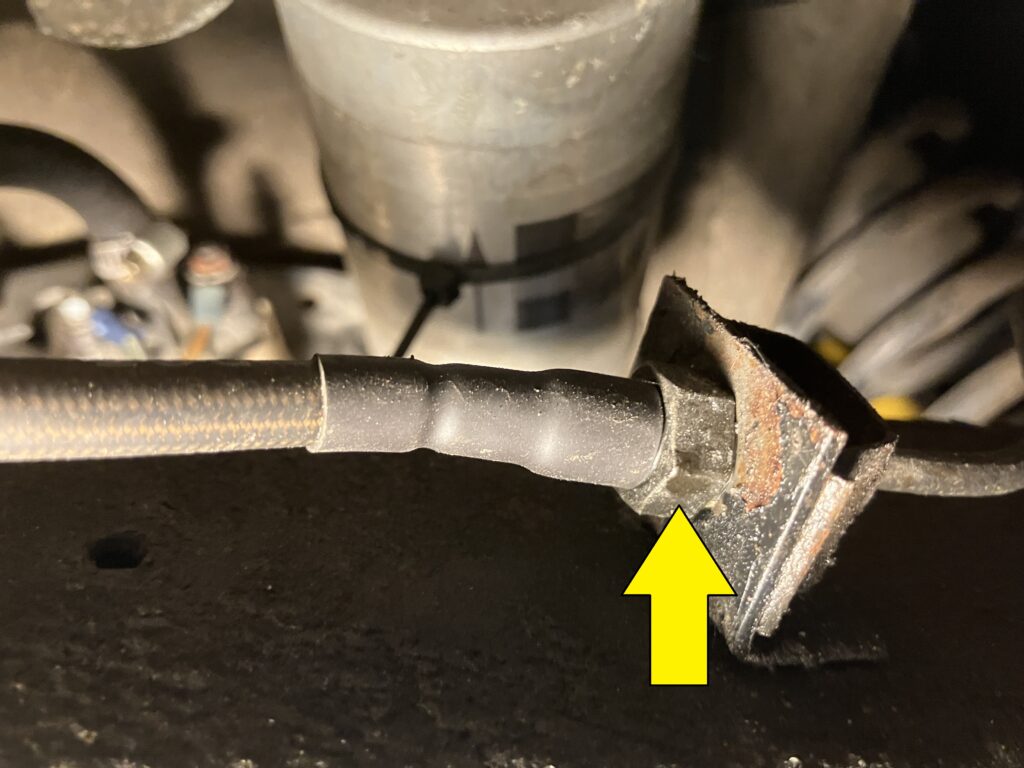

So I put it up on the mid-rise lift and had a thorough look. I expected to see a wet clutch slave cylinder, as I did with the Bavaria when I was readying it for sale, but it looked fine. I traced the hard and flexible brake lines from the reservoir to the master cylinder to the calipers, and the only thing I found was a dab of wetness on the fitting to the left rear caliper. It certainly didn’t look like enough to drop the fluid level by as much as it did.

Was THIS the cause of low fluid in the reservoir? I was doubtful.

I was about to drop the car back down and check the engine compartment further when I decided to take advantage of having it in the air to, as Austin Powers said, “Give the undercarriage a bit of a how’s your father” (those wacky Brits). Seriously, I’ve long said that one of the reasons to do mundane greasy things on your own car like change the oil is that it’s an opportunity to give the car a well-check. In addition to the usual coating of grime, oil, and power steering fluid, I saw a shiny linear streak on the lower radiator port. On closer examination, it was clearly coolant.

An unwelcome surprise.

When you find coolant down low, you need to see where it dripped from. My assumption was that it traveled from the thermostat or water pump down the lower radiator hose, but they were all dry. That left the lower hose connection itself. I put a screwdriver on the hose clamp, but it was already pretty tight. That left the lower port itself. If it was cracked, I was going to be right bummed out.

Then I saw the 22mm screw-in plug that’s there to close a threaded fitting for a temperature sensor that isn’t used on this car. Just to check off the unlikely possibility that this was the source of the leak, I grabbed a 22mm wrench to tighten it, and was stunned to find that the plug was completely loose. We’re talking not even finger-tight. We’re talking zero tension on the threads, zero pressure against the sealing ring. Holy smokes. It could’ve easily unthreaded in the next hundred miles and caused sudden catastrophic loss of coolant. I tightened it down, and vowed never to take the “it’s a well-sorted car” thing as gospel again.

Having missed this bullet, I continued looking at the undercarriage. The only other thing of consequence I found was that the giubo was cracked.

This one I’ll just watch.

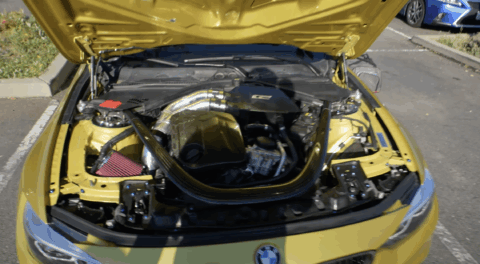

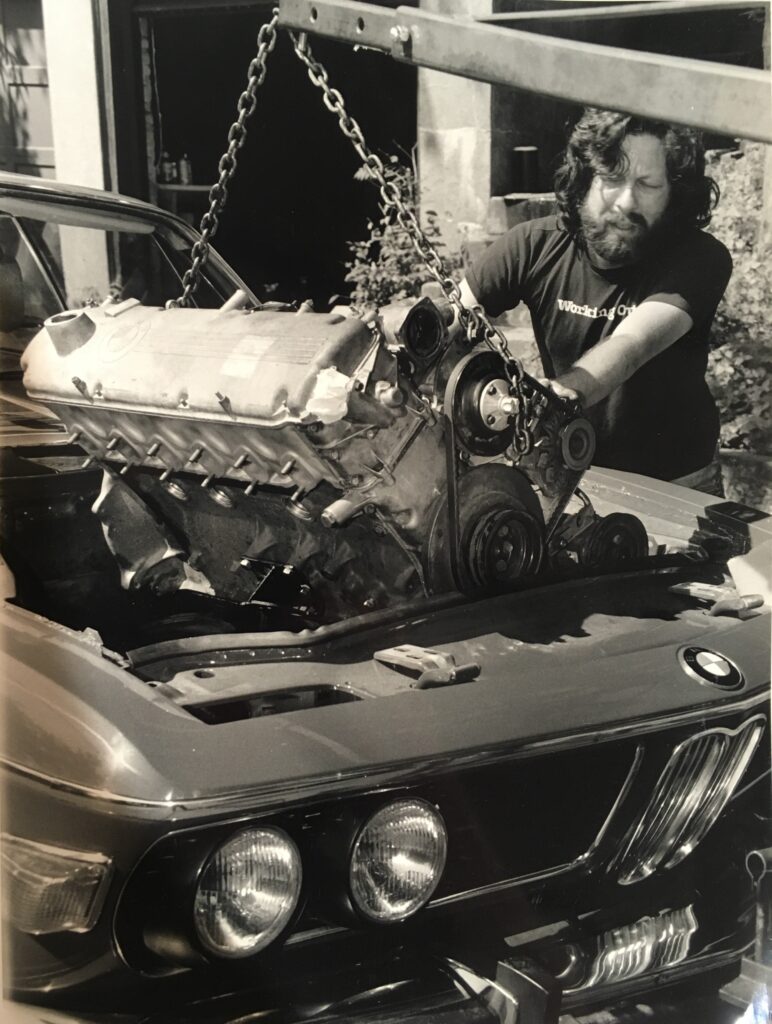

However, unlike the negligence I felt at finding the loose radiator plug, the cracked giubo made me smile, as it had been in the car since I installed the five-speed Getrag 265, and that dated back to replacing the engine, which I did on the streets of Boston in front of my mother’s house. I remember that the car had recently been painted (not the smartest order of operations), and I was desperately trying to swap engines without scratching the new Signal Red paint. All this was done in 1988. Owing to the poor quality of new parts, you certainly wouldn’t get 37 years out of a new giubo now.

Curbside in Boston, 1988. Photo by Yale Rachlin

I also had to smile that the car is still wearing the HeaderCraft headers and PrimaFlow exhaust that I bought while Ronald Reagan was in office from Performance Automotive Parts in Glastonbury, Connecticut. The headers are still fine, but the muffler blew a hole a while back for which I wrapped it in chimney pipe, and the center resonator will soon need the same treatment, as it now has rust pinholes.

I’d certainly get called out for THAT if I ever put the car on Bring a Trailer.

I still have the receipt for these exhaust parts, and as it’s dated 1986, it means that I installed them when I was in just-get-it-running-even-though-it-looks-like-crap mode. Again, a remarkable lifetime.

Wonder if the warranty’s still good?

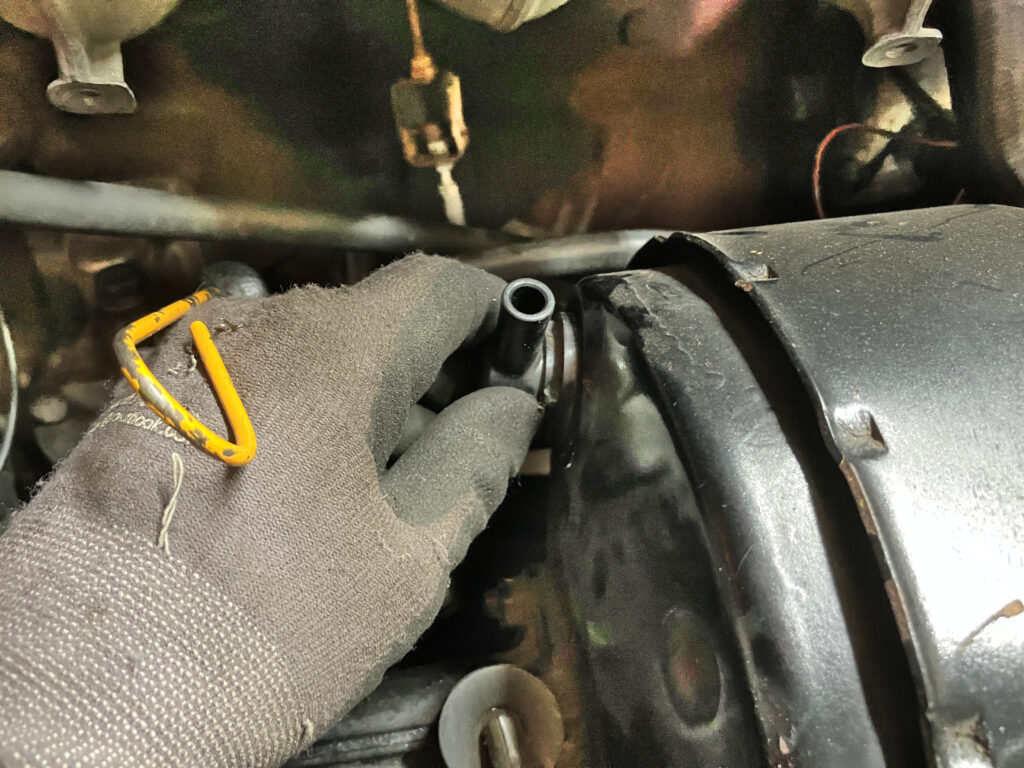

With the undercarriage inspection completed, I returned topside. If you have brake fluid loss and can’t find where it’s going, there’s the possibility it’s leaking from the rear seal of the master cylinder into the brake booster housing. The booster in the CSi is huge. I undid the hose and carefully twisted the plastic fitting off the booster.

I said “carefully.” You never know when a plastic piece like this is unobtanium.

This allowed me to carefully slide a long zip die down to the bottom of the booster housing. Fortunately, it came up dry.

A clean zip tie is a happy zip tie.

So where was the brake fluid going?

The only other thing I could think of was the clutch master cylinder. On a 2002, this is down inside the pedal bucket where the problem can fester unnoticed. It’s not uncommon to lift up the rug and the foam covering and find that the master is leaking from the rubber bellows and the bucket is full of brake fluid. On the E9, though, the pedals come down from the top, so the clutch master is up high under the dash. I thought that, if it was leaking, I’d have noticed fluid dripping down, but to be certain, I undid the kick panel below the steering column and looked upward. Even with a flashlight, the master is difficult to see. It looked dry, but I ran my ungloved hands all over the master, the bellows, and the push rod to be certain. This was an act of love for my E9, as I hate the feel of brake fluid. Fortunately, my hands came up dry.

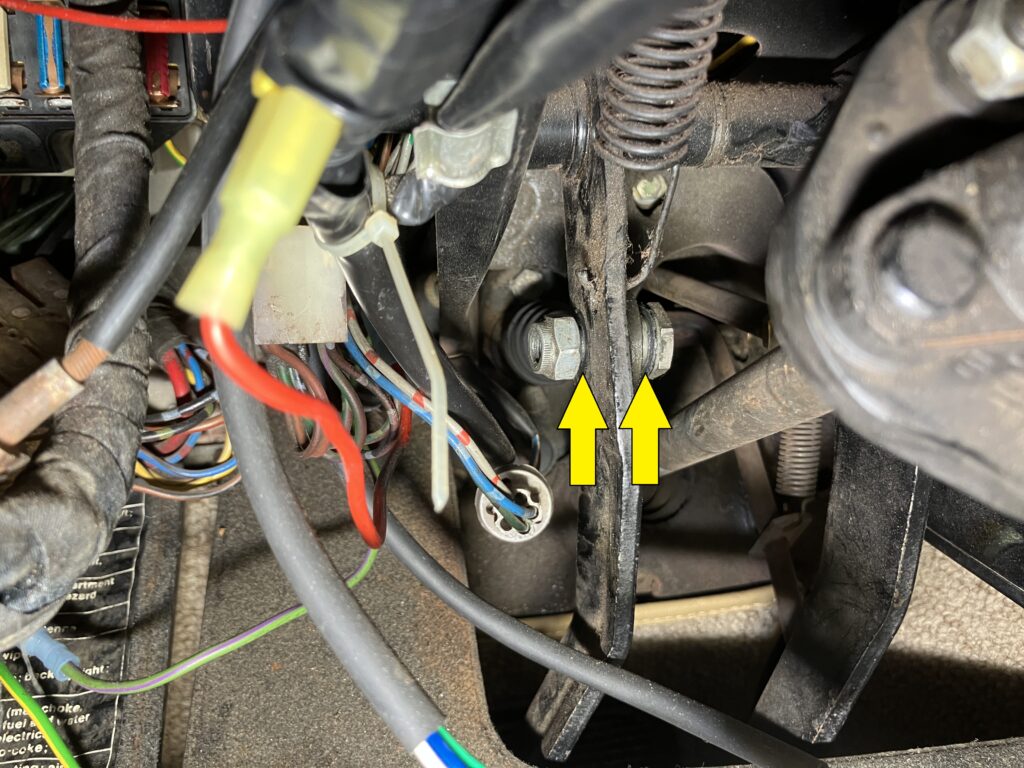

But while I was looking, I noticed that the nut and bolt connecting the lever from the clutch pedal to the pushrod were at an odd angle. I worked the clutch pedal up and dawn, and saw that the bolt was just flopping around. Not unlike the plug on the radiator, the nut and bolt were so loose they were about to fall out. Obviously I tightened them down.

Both the nut and the bolt should be flush with the sides of the lever arm.

I long ago added clutch hydraulics to my list of things likely to strand a vintage car on a road trip (the others are ignition, fuel delivery, cooling, charging, and belts). In fact, the clutch master cylinder in this very car died with zero warning fairly close to home about fifteen years ago. Who knows? Maybe I never tightened the pedal bolt down in 2010 and have been living on borrowed time ever since.

I’m still not sure what caused the brake fluid loss, so I guess I’ll have to give it some time, drive the car more, and keep inspecting it. But the larger view of things is that I’m going to begin regarding “well-sorted vintage car” the same way I regard “known-good component.” That is, maybe it is, maybe it ain’t, but making assumptions is likely to get you into trouble.

—Rob Siegel